|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Seeing Nature at PAM

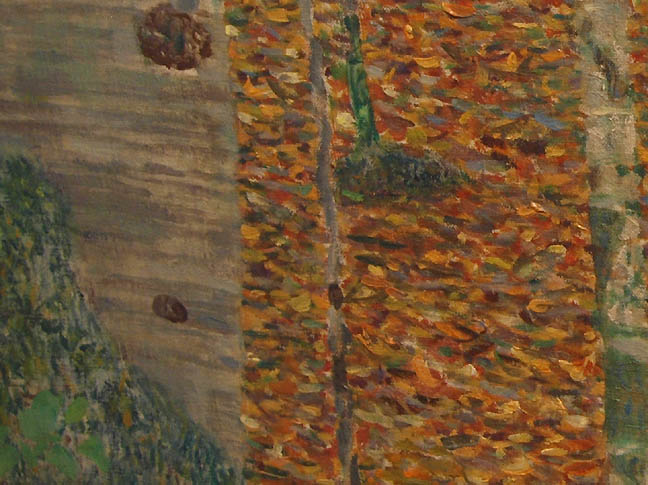

Detail of Gustav Kimt's Birchenwald (1903) at PAM (all photos Jeff Jahn) Today, Seeing Nature drawn from Paul Allen's collection opens to the general public at the Portland Art Museum. The traveling exhibition originated with PAM in conjunction with the Seattle Art Museum is a kind of survey of landscape paintings throughout history and as such maps the shifting expectations that viewers have for looking at what we consider the outdoors. One thing I very much like about the exhibition is the way it treats cityscapes as a part of nature and the landscape, thus to "See Nature" we have to see our own role in it. Though not every work is a "masterpiece", everything is very very good and several are of that caliber... the Cezanne, Hockney, Ruscha, Moran and Klimt in particular are paragons in their respective artist's ouvres. The excellent Monets will receive a lot of attention but I particularly like how this is not yet another impressionist show, it's a historical tour of painting the outdoors. It isn't comprehensively exhaustive (no Kirchner, Klee, Constable, Rubens, Lorrain, Mondrian, de Stael, Homer, Wyeth, Franz Marc, Picasso or de Kooning... but that's a billion+ shopping list and a lot of the best work is already in museums. (That's why contemporary art is a better bet and its inclusion in the show gives it scope, the Ruscha was a smart, even crucial inclusion). Like any single collector show Seeing Nature presents some of the particular tastes of one person... in this case a tech pioneer. As such it concentrates on the fictions we want and need to believe in... nature as an escape from ourselves. Thus, this is the anti-selfie show and with its background in the neuroscience with landscape being good for our mental acuity there is a twist here. Neuroscience and art rarely speak to each other (mostly because contemporary art are does a lot of navel gazing) but this exhibition makes a great case for itself. You will want to see this show again and again as it reveals the limits of using a computer screen to stream life into. I don't want to spoil the show so I'll bring out a few piquant thoughts and only show details of the works here. Every painter should see this exhibition. You should also check out Arcy's very topical essay on Art and Nature here.  Seeing Nature is refreshingly sited in the original Belluschi designed European art galleries. Well installed, it also feature copious amounts of comfortable furniture, running counter to annoying museum blockbuster trends which are focused on moving as many bodies through space as possible. This resurrection of the old pleasures of extended and uncluttered viewing at museums is exciting and commendable. These are among the best galleries at PAM.  Detail of Jan Breugel the Younger's The Five Senses: Smell (1625). The exhibition kicks off nicely with a suite of paintings copied from Breugel the Elder by the younger. This establishes the sense of tradition and the sensual element that all painters must contend with. In those days "Nature" was a backdrop or a tablecloth on which to set the visual meal and a way to foreground morality. Painting was an exercise in allegory.  This detail of Pierre-Jacques Volaire's depiction of Vesuvius erupting (1770) is still in high allegorical mode but Nature gets to clear her throat so to speak. More romantic tinges are creeping-in as nature is portrayed as potent and impossible to control.  This detail of Gustav Klimt's Birchenwald (1903) comes from a very important time in his development. From 1901-1904, during the artist lived at his Lake Attersee summer retreat where he would get up early and wander the woods... a bit like Thoreau or John Muir. Apparently, the locals dubbed Klimt a "Waldschrat" or woods hermit but his time there produced a number of forest scenes, each copse focusing on a different type of tree. By the time he painted Birchenwald or birch forest he had completely removed the horizon and sky from his pictures (something Monet does very late in his careeras well). Instead of expansive landscape there is a dense almost claustorphobic or presentness to the woods... not oppressive but but it gives a sense of the repeated density one gets when alone in the woods. It is almost like stained glass at a cathedral as everything is flat. In fact the trees are painted with very flat texture but the leaves are full of painterly scumble... thereby catching the glint of light in the room the viewer apprehends the painting from. The effect contrasts the trees, making them act like silhouettes without being dark. The close proximity and condensed space later becomes a hallmark of his best known figurative work but in many ways these are my favorite works by the artist.  By the time of this John Singer Seargent depiction of a chess match (1907) there is a sense of leisure within the contest yet the background of the stream and the figures in the foreground are treated as aesthetic analogues. Man is no longer separated from nature but everything is part of a game.  This Mount Sainte Victoire (1888-1890) painting by Cezanne is perhaps the most art historically important work in the exhibition. In the detail here you can see how Cezanne has deconstructed landscape into painterly proxies of mottled color. Cezanne painted many of these and as a group they are crucial to the history of Western Art. Instead of treating the history of painting and nature as separate they are equivalents. Cezanne is also noted for constructing a visual path or road through his works but here it becomes only something vaguely implied. It is the viewer which finds their path through the work. There is no more allegory and the painting is a painting, the mountain is a mountain in the mind of viewers... for the painter there is only painting. Painting is nature as a function perception. To this day these Cezannes are some of the most radical artworks ever produced. Their influence on Picasso, Matisse and Klee (perhaps the three most influential artists of the 20th Century) cannot be overstated.

By the time we get to this great Max Ernst from 1940 we can see how the surrealist has employed a somewhat mechanical process of lifting glass off the surface creating fractal induced fingerings of instability to manufacture something we visually recognize as landscape. It also looks a lot like a Star Trek set. Later computer programmers would employ mathematical algorithms that produce similar effects for video games. People do not readily make the connection between surrealists like Ernst and science fiction but sci-fi absolutely draws upon it. I'm certain Paul Allen knew this immediately though. One of the reasons tech and the art worlds don't communicate much is the art world is often uninterested in what bleeding edge tech is up to. Instead you have curators which follow curatorial trends rather than looking at the sort of art that is in communion with deep technology and cognition. Message... pay attention to the geeks art world. Max Ernst certainly would have.  By The time Ed Ruscha paints this great standard gas station image we can see landscape as a series signs and signifiers we see from a car. Everything is labeled and branded from the road and the diagonal of the sign and building remind us we are exploring a forced perspective. We forget that human activity become landscape but Ruscha foregrounds it. Read our interview with Ruscha here.

Last but not least is Gerhard Richter's Vesuvius (1976)seen in detail here. It is explicit in the way the viewer cannot fully comprehend or experience what they are seeing. It is an expression of limitations which 21st century man takes for granted, our powers of perception are limited only to the degree that we acknowledge our limitations. Seeing Nature runs through January 10th 2016 Posted by Jeff Jahn on October 10, 2015 at 12:01 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |