|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Interview with Michael Lazarus

So I went in to see the instructor and showed him my work and he said, "sure you can be in this one class that I have." It was where the students just meet and they do what they do. So I was in that class where there was one particular student that was one year older than me and he was painting these really expressive oil paintings that were portraits of his friends. He was using the back of the brush to paint them and they had a lot of texture. It was experiencing his work and being with him every week and his energy that made me realize that I could do that and that I wanted to do that. That I enjoyed it. It was kinda how it began and I got on a fast track to getting my shit together and ended up being accepted to the Rhode Island School of Design. JJ: So did you move around a lot when you were a kid? ML: Only one time but it ended up being a pretty formative move. I grew up outside of Boston but then we moved to South Florida. The school system outside of Boston was really pretty good but the one in South Florida was massive and kind of neglected. The culture was radically different and we moved when I was 13, which is a bad time to do anything (laughs). JJ: So THAT was why you decided to not do art at that time? ML: Yeah, that was the same time. I kept doing it right when I moved but it sort of became lost... it was going in that direction. I can still see all the photographs that I drew or copied and how there was this void of engagement outside of the technical.

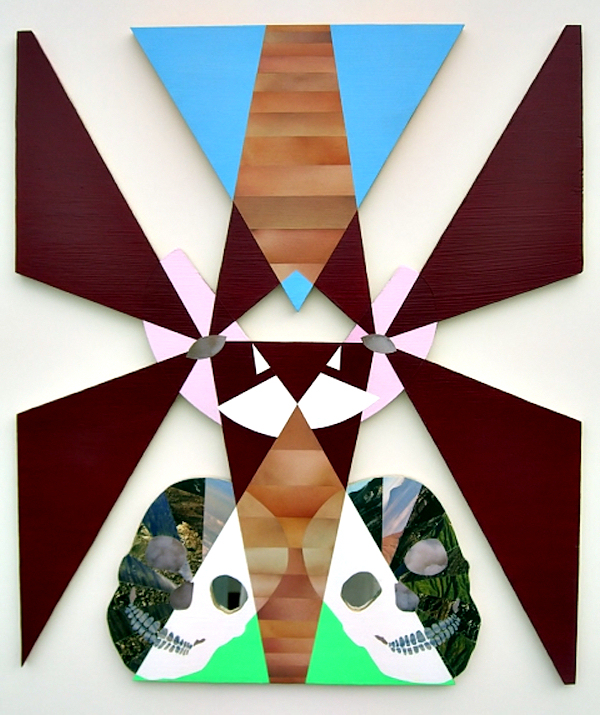

Which is all to say... to my eyes it seem like symmetry is very important in the work... not simple symmetry but you set up symmetrical situations in order to break its unifying aspects, which is also a zen principle. Where did that advanced sense and use of symmetry come from for you? ML: So after RISD I went to graduate school and in the middle of my first year I came to a realization of what kind of work I needed to make. Not exactly what it would look like but what kind of work I needed to make for myself. One of the criteria was that it have representational elements in it and use a lot of abstraction... and that it be narrative but not have what we now call a linear narrative like a story narrative. So the tried and true format to try and create that is a symmetrical composition. It's because the symmetrical format takes something from the story narrative and turns it more towards portraiture. Maybe it isn't always the portraiture of a person but it can be a portraiture of a landscape or of a face... or a portraiture of a sensation or a feeling without the story of, "the little guy who climbs across the mountain top to reach the castle."

JJ: In your last show in Portland (and later Participant in NYC), the eyes were extremely prominent in the compositions. Whereas in earlier works like Small Craft Advisory... very good title by the way, with a very loaded art commentary that refers to your own history it seems. Whereas, with these newer ones, did Max Ernst and Joan Miro's influence have any bearing on this shift to personages? Or is it a rejection of landscape that creates a proxy portraiture?

ML: Yes, in some ways all of the things you just brought up. Max Ernst, I don't think about him very much on one hand... but on the other he is one of my favorite artists and his work is so engaging for me. I just fall right into them. Overall, I think I've always done a lot of works involving heads or portraits to a certain extent. Sometimes, I haven't and I've gone more in the direction of landscape. Lately. I guess I've given myself even more freedom to do that... in a more overt way. And that allies a lot with giving myself the freedom to make the eyes more engaging. Usually, the eyes are very blank and here they really engage and speak to the viewer rather than as voids. JJ: In the past you have used a lot of skulls with snakes but now they are more phantom-like and less of a vanitas and more of a mask. Obviously a vanitas is related to mortality and a mask is more of an unknown situation.

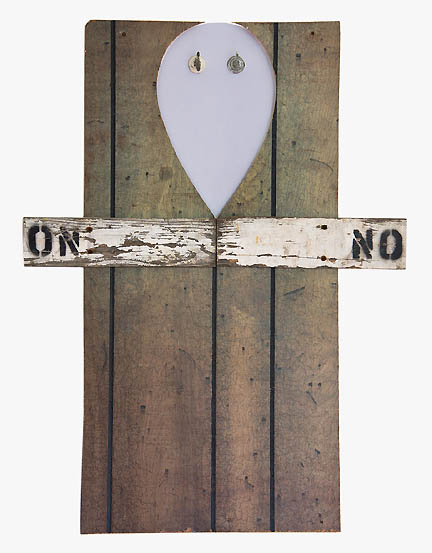

ML: Well, these are more of a return to the heads I was doing in the mid 90's and a few years ago I started using skulls for a bit and now that is out of my system. I was doing skulls when skulls became very popular in pop culture and I really didn't like that but I couldn't stop using them. I was like I don't want to use these now because they are on t shirts everywhere but I needed to keep using them. But now Im in a place where I've returned to these heads but if you look closely they do have a mouth they a half serpent mouth and a triangular nose. Though, most of these works you saw mostly just have eyes? JJ: Yes. But they still have eyes that are more like the absence of something, or maybe a reflector. Often like the one that says "Sorry" on it the eyes are cut out. Which pivots us nicely to another thing we I wanted to ask you about, your use of language? Every work in the Portland show except one made use of the word no or on? Sometimes it was the homonym of no as "know" or on and if it isn't in the title it is actually on the piece. Obviously, there it is very specific symmetry to no and on but where is that focus coming from? ML: It came through process. The past 2 and a half years I've been using words and most of them are found on signage. Earlier I did work where I photographed the signs. I printed them and I collaged the image in so now I'm using the physical signs themselves. And I've found that a lot of sign involve the word "no." So that kept on recurring in my gathering of material. Then as these signs sat around in my studio I saw them up-ended. At that point the symmetry of "on" and "no" asserted themselves. Also, in many of the titles I have used in the past I've used plays on words that look the same but mean different things. In this case it is the same signs in a different order that mean different things when it is flipped over. JJ: Which is analogous to the idea of using collage, which has seen a resurgence lately and you could what you do collage. It has its roots in Dada, something which probably is a bit of an umbilical connection to Ernst but I've also noticed you are using infinity symbols. What are the roots of that symbol in your work? ML: Yeah, where did that come from? I'm not sure. I know I've used it in other paintings but I am not certain what the first one was?

ML: The snakes definitely have that sort of aspect to them. And though I've wanted to I've never been able to use the snakes eating itself symbol (Ouroboros) JJ: The Midgard Serpent thing from Norse mythology where the snake eats its own tale? It came from the Greeks and was also an alchemical symbol. ML: It has been too loaded a symbol to be able to use effectively yet but maybe someday. So again I think the infinity symbol is this both symmetrical where one part leads into another part. That cycle fascinates me. Also the idea that two things that may seem opposed yet existing together. It is at once going out and expanding and simultaneously entering in and contracting. JJ: That is very similar to a street sign... it may block one path but it usually indicates another one.

ML: There are so many signs that are all meant to help us but at the same time so many are telling us to leave or stop... to not to do something. I started working with signs before I moved here but I have to say that Portland is very full of signage. Im not sure why. Im not sure if there is some city code that says if these steps are "slippery when wet" they must be marked. Have you ever noticed the sign across the street from Powell's (City of Books) that has about 5 paragraphs of things you should not be doing on that sidewalk? JJ: Maybe it is just that sense of civic responsibility that wants to be explicitly stated? Because in New York City there are signs... but maybe its just something covering a manhole. ML: Here there are construction barriers, twelve of them. In New York it might be like a garbage can with a piece of clothes line attached to it. I'm not complaining and some of the signs here are super helpful but sometimes... there is... [pause] there is a lot! JJ: There is that spot underneath the Fremont Bridge where they store tons of signs. Have you seen that? ML: Yes I have and all those construction barriers and all of the companies that fix sidewalks they put out a load of those but those they must do because it is required. Whereas in New York it would be a clothes line strung up between 2 garbage and it would be the only thing telling you not to walk on the wet cement. JJ: It does force you to pay attention or else you fall into a subway shaft. ML: So I LIKE seeing all of the signs here. JJ: In LA the freeways are so good and well designed and everybody know how to merge... perhaps because you will get shot at there if you can't merge but here drivers tend to be either over eager or simply not paying attention and just driving in their own haze. You are right though, there is also a ton of signage here... one reminder every mile until you get to your turn. Yet for the most crucial point where you turnoff happens there is nothing. ML: That's true... because you get to rely on those signs. You are ok this is good I've got one sign then another then another... then they are gone and it is, "wait I don't know what to do." JJ: That reliance is interesting. I wonder if that goes back to the Governor McCall days of, "Visit but don't stay." We want to seem welcoming but not too welcoming, Portlanders have terms. That's a good lead into the ubiquitous question, "what brought you to Portland?" ML: It was just a family decision but in relationship to my work as an artist, I had been in New York almost 20 years so I have a lot of good friends there that are artists. All of whom were really helpful peers to have but in terms of the art world there. I had become fairly disconnected from it on a social level so I began to question, "So why am I here?" JJ: It is sort of the thing that happened with Jackson Pollock (who moved out onto Long Island after he made it). It is an old story many famous New York artists go through. ML: A little but I don't want to make it sound that dramatic. For me it was, "Well I've been here quite a while, I'm not super engaged with being here and I've never lived on the West Coast and Portland is such a unique city and so interesting." So I felt it was time to try out life on the West Coast and see what that does to me and my work? Besides, it is so easy to get a flight to New York and LA to visit. And honestly, you often only see somebody one time a year when you live in New York. JJ: That's funny and perhaps that is part of the appeal of a smaller city, you manage it... it doesn't manage you (financially and socially). Still, I've got acquaintances in Portland that I generally only run into once a year on red eye flights to New York City. ML: Even I red eye it now. I'm gonna go in a few weeks and I'll see how I like it. If you want a direct flight they are all red eyes.

JJ: Back to the work. One piece that really struck me was the "On No" one with the two coat hangers where the wall behind it is painted lavender to complete the piece. That to me seemed like a new development because It isn't all a found object. What do you consider it? ML: That is a good question, I still consider all these pieces paintings and it is because you approach a painting different than a wall bound sculpture or a construction. So there is that. It is placed in the context of painting and I like that context. It's definitely in the discourse of painting. But then again we are living in a time now where the definition of what is a painting is expanding and expanding and expanding. So I embrace that and it just so happens at this time that my interests are going in a direction where I'm more and more interested in the quality of the object of a painting and with that comes the interaction with the space around it... and the space that is directly around a painting that is hanging on a wall is the wall and so for quite a while I've been doing pieces that are shaped or have voids cut out of them and in that way they interact with the wall. So I guess it has been the next step. Eventually, I think the next step would be to make some of the work on the wall itself. Still, it is a painting as a singular object that can be picked up and moved. It isn't site specific. I don't need to go and install it each time it. I like that idea that it is an object that can travel to spaces that I may or may not choose. Then it can interact with those spaces whatever way it may be. We don't say, "I made this painting on a rectangular stretched canvas and it must always be shown on a whitewall." Maybe there are some artists with that written into their installation instructions but it is pretty rare so when I first started cutting voids out of paintings that was the immediate first thought was that my color choices on the painting would be in response to white or white with a shadow in these voids. But it may not be white on another wall... and do I want to stipulate that is must always be on a whitewall. I decided not to and I decided that that interaction be it a brick wall or hanging on a whitewall I thought that was exciting, having these interactions that were unpredictable. Which is letting go of a lot of creative control, especially when it comes to color and I'm a very strong colorist. So I let that happen and now I've taken the opposite angle. Here it will not be on white... It will be this specific color that must be painted on the wall. JJ: there is something very succinct about your work... installation artists are notorious ramblers (though there are always exceptions) but stereotypes exist because it isn't uncommon... like photographers being highly technical and observant, of course they often are. Collage artists are often very succinct... because things get muddy very easily. In your situation you are making collaged paintings that have that succinctness that I appreciate. Perhaps it is because a lot of work in the last decade has been "piles of stuff" or a mound of material that obscures itself ...where more is more is more. It's a party mentality where distracted attention is the goal over prolonged attentiveness. Whereas in your work everything has a back story but it is like sushi. Each element is there to shine and support without obscuring another element. ML: Thanks JJ: It has a very discrete intentionality... even a discrete personality to this decision. By that I mean you didn't just go and paint a big perimeter around the work. Everything I've ever seen you do exercises a great deal of discretion. Obviously that is on purpose? Maybe it comes back to the signs, which are very much about exercising discretion and making discrete directives. Walk, don't walk... it is very explicit. ML: Well I think that is why I am so interested in signs. Because of that. Early on the gallery I worked with in new York, Hudson, he early on described my work as signs. Early on I was even using sign paint. I've always really liked signs... a sign is a paining and it is a type of painting that really emphasize being an object. Those are aspects that are of interest in my own work. I've also been interested in eastern religious paintings, which are also in a way signs because they are pictograms and pictorial in their depictions of a certain deity . They also a use a lot of the same tools at hat I do. Symmetry and bold colors. Where am I going with that? Signs... I'm interested in them. Which comes first the chicken or the egg? Am I interested in sign because my paintings share similar sensibilities? JJ: It is an engagement with the history of paintings because the cave paintings of Lascaux are signs. ML: Yeah and I really do like paintings that have more of a functional aspect. Throughout history paintings have typically had a more functional aspect to them and only recently have they become a more sophisticated type of more sensual type of experience or emoting something. I'm interested in both of those things really strongly. It think Ernst is one who does both, which is why I like his work so much.

JJ: There is an inherent anthropology that you share and expand upon... you turn the wall into a character. There it is the wall staring back at you. It is as expressionless as a wall or an idea but with the engaging presence of a personage's form. It personalizes the impersonal background aspects of culture... rooms, signs etc. ML: I don't think anyone has ever said it quite like that before... Posted by Jeff Jahn on September 01, 2014 at 11:45 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |