|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

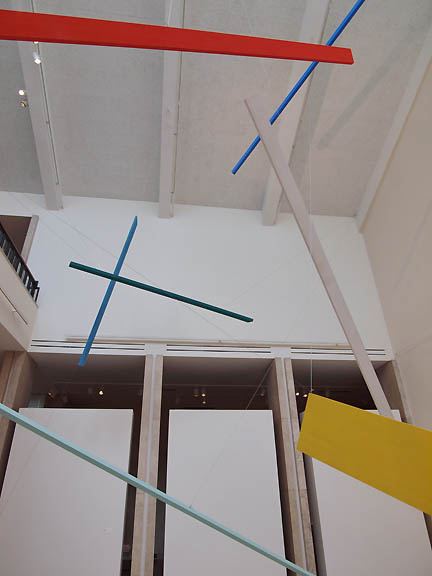

Interview with Joel Shapiro On the occasion of his latest sculptural work titled "Portland" at the Portland Art Museum I interviewed Joel Shapiro just as he finished installing his latest constellations of parallelograms. For an artist who has been developing a post-minimalist studio practice in an earnest manner amidst an increasingly ironic world, Shapiro continues to investigate the concrete beauty of form and color and the liberating pull of taking a media where it hasn't gone before. VM: For an installation of sculpture your "sculpture" isn't acting like that. I see plinths and pillars and things that should be planted on the ground having their way in the space.

JS: Right, actually no, I mean I think that this work there was a certain point where I wanted the effect of architecture, let's say the effect of gravity on the organization of form is serious and profound. If you're working on the tabletop or if you're working on the floor or if you're working on the wall it informs the way the work, the forms, become organized and I was just fed up with that. And the work began to break up around 2000. Eventually, I just thought it was more engaging to suspend stuff in space and let it not be determined so much by the structure of the space but more by the nature of the space, if that makes any sense? VM: It makes a lot of sense. JS: What I mean about structure is walls, floors and of course this is all determined, so in a way the string becomes the base and the pedestal, the string becomes the bolt that is, which is holding the stuff in place within a kind of confined space. VM: Well, without being heavy-handed I think you reveal structure not to be something girthy but actually something maybe a little bit more provisional and resilient. JS: Yeah, I mean, you know I built a model of the space in my studio that was 1:16. It was really big. I did an entire mock-up of it and kept rearranging it. And, you know as soon as I began to install it I changed it [laughs]. VM: So talk to me a little about that in terms of your motivations for doing it? JS: Originally, the yellow piece was way up in the window. You know, I was trying to expand and engage the entire spatial situation and you know this piece changes as you walk around the piece. Unlike, well, all sculpture does, but this sculpture more so because you come in to it and you participate within it and then it reconfigures. Well, you come up with structures and you see what you've done and what's not going to work. What I keep trying to do is keep conscious of the main axis of the museum is in front of us from the two main entrances and as far as avoiding that to some extent. And, actually this is the first time that I've done this stuff without actually anchoring to the ground. VM: I see that. It's a bit jarring at first. You were talking about how you wanted to move away from the necessity of gravity. Having to either install work on the ground or stuck to the wall? JS: Yeah, and these are all determined by gravity, too. They are all hanging. Nevertheless, they are not stopped by a wall or the ground, they are determined by the wall, it's complicated. VM: It's rare to experience work from both the ground floor and upstairs on the second floor open balcony. JS: If you walk around the room it constantly reconfigures. And this is a big space.

VM: So talk to me a little more about what changed between the design of this installation and making it work for the space. JS: Well, you know, I made this red piece for this space and that's thirty-two foot because I wanted something that transitioned from the entry, the under-hang, up into the vastness of the space. And, I have a yellow piece way up on top and that black piece down and the whole the whole central section seemed empty so I inverted the two. I inverted the two, I pulled the yellow one down and dropped the black one further down. And, that piece, I don't know that orange color, pumpkin color, it actually looks like papaya, that one was much more horizontal. You know we put it up and it didn't work but I left it up because it's kind of falling down. VM: The work seems to be about freedom. Talk to me about freedom. JS: In terms of freedom you just kind of stick them in space. The problem is to be free and not anchored and I think, you know, it's like anything else. I mean if you sort of, if you're attached to the page or attached to the floor as an artist, or attached to a surface, there's freedom within that but it's more focused. I think this thing is a little looser. There are any number of configurations. VM: This feel closer to the kind of constructions that Helio Oiticica was making before he passed away... JS: I don't know his work well - I should. VM: It's suspended but it gives me that same flavor. Knowing the limitations of the forces that shape the thing. But, really, being free of them. JS: There are a million ways of doing it. VM: When I look at the work you've done over the years it's refreshing that you've landed on simple, existential moves that keep yielding more and more beautiful results. Is that part of your initial training or is that something that you've really garnered over forty-plus years of making? JS: You know you keep working and you keep working and I think you're always aware of the limitations of the work. This isn't spelled out in a program. You know of certain limitations in the work and you find out that if you continue to work the more there is nothing new to discover and it's really boring. VM: So talk to me about how this work reinvigorates your investigation formally, conceptually? JS: Well, I think it allows me a broader sense of freedom. To throw things in the air and then lock them in place with string. I don't have to build an elaborate structure. Although, this stringing and all this stuff ends up being quite labor intensive [laughs]. VM: It looks effortless and simple. JS: It took us three days to do it. VM: And there again lies the trick.

JS: You have to have good anchoring points into the building. And I just think that it's interesting that it depends on the building but it's not really formed by the building. So it has this nice symbiotic relationship with the architecture but it's not an extension of the architecture. If anything it's antithetic to the architecture and I think that's what's liberating about it. And I do think that you can project color in them. I'm deeply interested in the color. And, I've built many of these things around various metaphors, too. I mean, it's not void of narrative, though I think this one is the most formal that I've done that really had an internal story, which I would never announce publicly because I don't know if it's important. But, I mean, there is a sense of purpose. VM: Share with me the part of the narrative that is important to you. I think I tend to understand what you're talking about in terms of explaining a narrative that might not help understand the work? JS: I was thinking, you know, I'd think of black as absence at one point but then I would twist it all around. Some of these elements were shown at the LA Louver Gallery. Then I added them and extended them. I was really interested in sun, moon, earth, all these kinds of things, elemental. Trying to find a color. This is more about the color than the form. Trying to find it. Or the pink one, fleshy, more sensual, the one up there, that's all stuff I think about. So you try and load up or find a color and at that moment at least it has some meaning to you. I don't know how but I would never say that "this is fire" or "this is sea" - I think that's all crap. VM: It wouldn't necessarily support your idea of freedom if you held the people or the work to the narrative. So what are you calling this piece? JS: I'm calling it Portland. I mean that's how I refer to it in the studio. I'd say I was working on the Portland model. Bruce wanted to know a name for the piece and I said, "Well, we call it Portland." And, you know I think it's more how it avoids any aspect of statuary and any aspect of joining which is I think is really difficult. And, it's not dependent on the wall and floor. I think because of that it really does have a certain sense of exuberance. VM: I've seen the space overcrowded in the past, so the fact that your work makes it feel big is a point of success. JS: This is a big space. VM: Well, it doesn't necessarily mean that it will work for everything. Also, given your insight about color how we relate to the work really extends to the freedom because, you know, we have primary colors that we can engage with but also these very fun, design oranges, and fleshy pinks, and obscured blacks. Tell me what kind of other devices you have left for us to queue into - how to get around the work? JS: Not that many. VM: That's probably where the mastery lies? JS: I don't know. I mean I was interested in black and I was interested in aspects of green and I always saw this color, originally this color was going to be up high on the wall cause I was interested in the sort of spirituality... VM: The Celadon Green color here? JS: It's sort of Dark Malachite. Would have been something derived from Copper. But you know I think that's so long ago that it's not relevant. Now I just think it's about engaging form and space and the recombination of things. So you're seeing it, it's always some kind of other and it's always circumscribed differently or framed differently. VM: It feels like a constructivist invitation to explore. JS: Yeah. VM: Do you have a preferred avenue for viewing the work? JS: What does that mean? VM: You talk about wanting to design the work so that it doesn't necessarily queue into the entry spaces. Is there a point of view that is a little more prized? JS: Actually I don't. I mean I was sitting here, way back here, in the most obscure part of the thing, totally engaged. No, there's no preferred way. But, I mean I think it looks really great from the balcony. VM: I'm excited to see from above. It's interesting, too, to sit quietly with the work and notice that you've actually ordered and organized it in terms of cools and warms. It goes back to that metaphor of dark and light that you're talking about where the black and white have their own axis and the greens, the blues... JS: You know to some extent it is about the literalization of painting. It has a lot to do with painting. I mean of course as a sculptor I have an interest in painting. It's a kind of crazy approach to it. But it kind of works. VM: So, one of the questions I had earlier was how do you keep your studio practice so fresh when there are less and less choices to take? One of the things I'm hearing is that not only are you drawing from the past but you able to let go of the past when it doesn't really add to anything... JS: Yeah.

VM: And, you're able to have a dialog with sculpture in a non-traditional sense. You've gotten rid of the pedestal part of that relationship. JS: I want my work to be fast. I'm not interested in the slow and ponderous. I think, you know, thought is, we have thoughts, they develop. You don't even know you're developing and idea. And then when their actualized, when they come into the world, there is a rapid realization so I was trying to, with this work, with this kind of work, not this piece in particular, I'm just going to project these thoughts, I was doing it, you know, I was building pieces, sculpture, I was joining part to part. And, if you were joining one element to another, attaching it say flat to flat. Not unlike the arm attaches to the shoulder. It can only do so many things. So then I began to break them apart, break elements out, and have these very strange connectors. I began putting pieces together with wire and then pulling them apart until I found a meaningful configuration. And, then I decided to just pull the parts. Locked in space was meaningful enough. VM: Goes to show how there is a way to visualize even String Theory now with this sculpture. JS: That I don't know about. I don't think about that. VM: Neither do I, which is a really difficult thing to articulate. What is this underlying structure that affects all of us but none of us can really touch or see? And, in a way the first thing you notice when you walk into the gallery space are the volumes of color. Not quite sure how much they weigh and what they're made of... JS: Right? VM: Secondary is the string. Which actually is the magic. JS: No, I think the string is a kind of armature. I did beef-up the strings. This is a public space. Normally I would use thinner string but this string is super strong and I think it's good because it's in public. VM: How much do the objects weigh? JS: Well, some are hollow. Like that red one weighs about forty pounds. This one weighs ninety pounds. This is heavy. It's solid. The string can hold up to fifteen hundred pounds. VM: This is going to give some poor guard a headache - and a heart attack. Given the relative freedom this Portland installation gives us how interactive do you see these getting? Do you see people pushing on them? JS: No. I see people walking through. No pushing. VM: Very courteously? No pushing? JS: If I wanted this to be interactive I would have made it - I would have turned it into a swing. Or made it into a slide. I think interactive if they walked around. I mean really the only one you could really walk into is this one. I seriously doubt if anyone will. These are pretty massive. VM: You talked about this installation being a part of a larger body of work and of a thinking through. What other installations connect to this specific one? JS: Well I did an installation at Ludwig Museum in Cologne. I did a show at Pace Gallery of suspended pieces. And, you know really it was a breakthrough show. And the pieces were smaller and the string was barely there. So, some people really liked it. Some people found some string more there than other strings. If I used white string in here these things would really float. I've decided not to do that. That I'm using grey because I think the string is an essential part of the work. So, I did a show at the Ludwig Museum in Cologne, then I did a show at Rice University art gallery, which is very beautiful, and I did a show a LA Louver Gallery and then Paula Cooper showed the Rice piece but I made some adaptations. Some of these elements were in the exhibition at LA Louver. I reconfigured it entirely and added certain elements for this exhibition. This was not in the show - the red one. The blue one wasn't in the show. I think it's courageous of the museum to do it. VM: How did you get connected to the Portland Art Museum? JS: Bruce saw the show in Los Angeles. VM: At LA Louver? JS: Yeah, and he really liked it. Because it's radical. Posted by Victor Maldonado on September 13, 2014 at 11:45 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |