|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

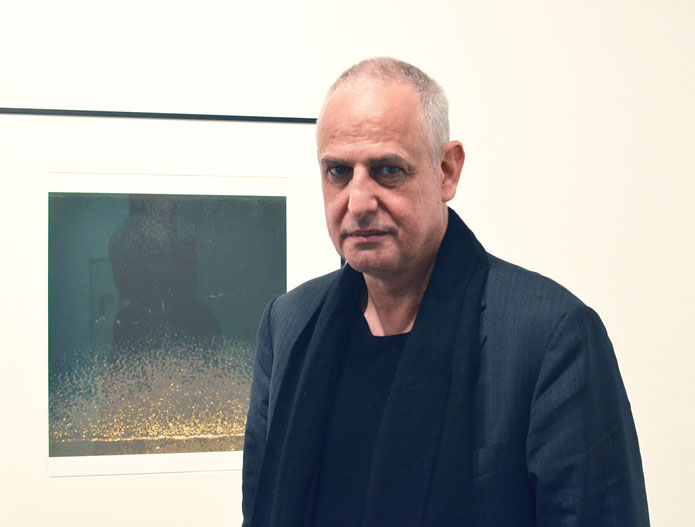

Let Them Look: An Interview with Luc Tuymans

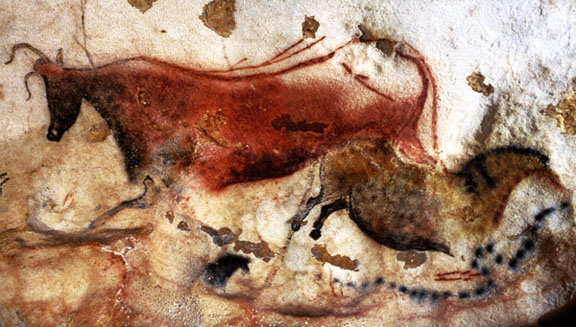

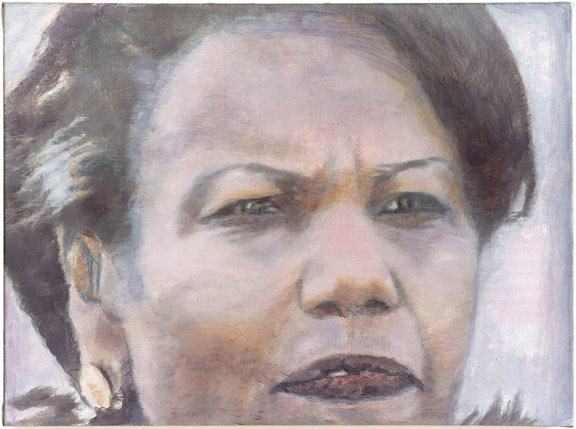

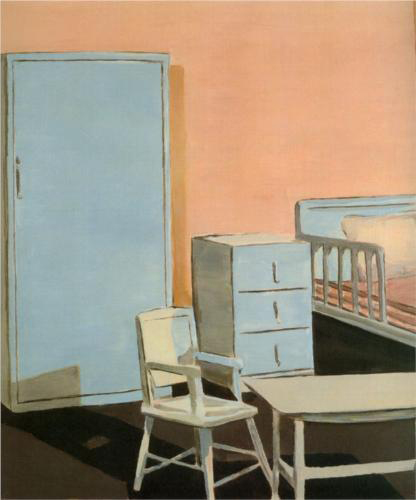

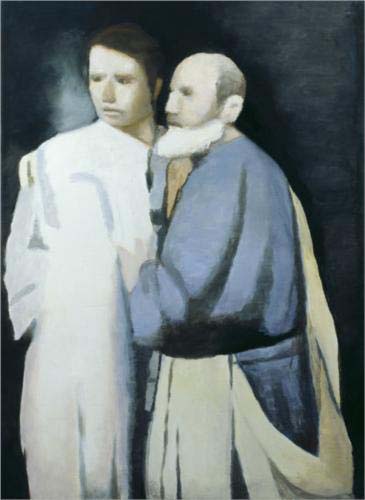

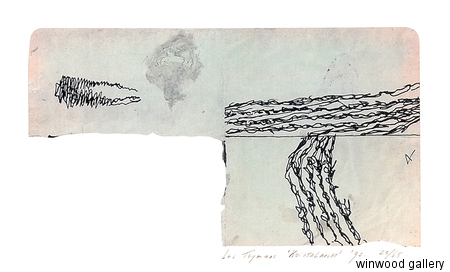

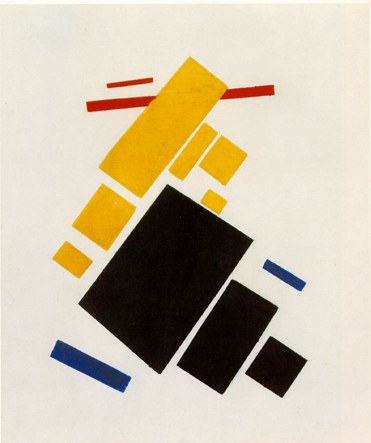

AB: You've often been cited as reviving painting, which has been deemed a 'dead' art form for many years now. How do you think about that? Did you/ do you think of painting as a dead art form? LT: No, never. The question often posed to me is "Why do you still paint?", and the answer I give I consider standard in the sense that I am not naive. Painting is the oldest and the first conceptual visual ever made, from the caves of Lascaux up until the grandest tableaux. Painting is also a much faster mode of expressive picture making than any technical tool because it is not bound to the same sorts of limitations. It is only bound to the physical capabilities of the painter. LT: There are tons of people that paint. As for me, having "revived" painting: I don't know. I was never busying myself with that to begin with. I was definitely painting at a time when lots of people were. And I was also working with figuration at a point when not many people were. Therefore, my first chosen small gallery exhibition was one that I paid for. It was a colleague's artist space that still exists, in Antwerp. He made post conceptual art. The gallery space was on the same street as a giant colloquium for the museum of contemporary art. People didn't talk about paintings then. They talked about conceptual images, which were paintings. (chuckling) AB: I read somewhere that you had abandoned painting for some time to study art history when you were younger. LT: That had nothing to do with the medium itself. That had to do with myself. I actually started out not as a figurative painter, but as an abstract, gestural painter. I used lots of color. Then I started to add figuration, but abstraction became very existential. AB: How? LT: Well, it was existential and tormented; you feel suffocated by it. You are too close to the thing. And then, by accident, a friend of mine shoved an 8 mm camera in my hands, and I started to film. That was from 80-85. I shot mostly Super 8, 16mm, and in the end, 35mm as well. Then I returned to painting. This was important, because this time period of four or five years allowed me to distance myself from the medium. And it was the distance which allowed me to make the image I wanted to make. I already wanted to make paintings with a sort of diagnostic view, but I couldn't because I didn't have the distance. Otherwise, filming continued to inform my paintings long afterwards because of the vocabulary I gained from using it: cropping, closeups, etc. Ideas came from looking through the camera, and I began to understand and accept that a detail could be blown out to become the image itself. That helped a lot. . .to come back to painting. AB: What does an image need to be to become a painting? LT: Well, my toolbox is very big now because I make either drawings, watercolors, tiny maquettes which I take polaroids of, my Iphone, websites, Photoshop, etc.. . . But the aim is to analyze the imagery in such a way that it becomes relevant to paint and that it will, through the act of painting, go through a transformation more dynamic and complete than any bound by just mechanics. AB: Can you describe the elements of an image that would be relevant enough to paint? LT: Well, to give you an example of what I am working on right now, I have a big show coming up in 2015 in Qatar. The exhibition space is 5,000 square meters. I am also going to make three mosaics for the Nation Museum of Qatar which will stay there. But during the last visit, the Emir asked me to make something having to do with the region. This new work would be combined with older works to produce what would be seen and considered as one body of work. The request from the Emir came as a surprise to me, because it's very complicated. It's a very difficult political situation in that region, and the Qatarians have a special role that they play. So I told them that I wanted to produce the a body of work solely with the region in mind. AB: There is a very delicate line between severity versus the mundane in your choice of imagery. Is there ever an aspect of irony or kitsch that plays into the images you select? LT: Sure, but one thing I have never succeeded in doing is making a happy piece. That I can't do. There is lots of irony in the work, yet not predominantly. I also don't think the work is overly serious. It is not happy. That's for sure. But on the other hand, it has impact. It was like I was saying before, the rabbi once told one of his sons, "Happiness is about thirty seconds. Suffering goes on forever." And also creates much more imagery, basically. Maybe irony is a bad word. . .sarcasm, or sardonic maybe is better. AB: There is something about it that makes me think as if you are endeavoring to create a more self conscious society, as if you wish the world to be more aware of itself as an act of morality. LT: Well I think, and this may be personal, but the reason we show artworks is in the least so that people should start to think and to distrust what they are looking at. AB: There is something about painting in particular, at this point. . .as if the proliferation of images is so profuse that choosing to paint something is an incredibly loaded act. LT: Because I am already working with appropriated imagery, it is very important to me that I know what my intention means. That is not to say that the viewer must see what I intend. But for me, to have the kick to make it, it must be meaningful. In terms of a moral stance, I don't really think so. Even in terms of my portraits, like the one of Condoleeza Rice, who is of course a major political figure, it is much more about the enigma of what the person is and what it meant to paint her when she was still the Secretary of State. Of course, a lot of people would see that in itself as a political statement, which they did the first time it was shown. AB: Yet at the same time, as much power as these images retain as paintings, there is also an aspect of remove. They seem as if they were images made underwater, as if the objects therein were the relics of a sunken ship. LT: There is always an element of distance because for me, it's very important what an image does from across the room. There is also the distance you measure between yourself as a spectator and the image itself. AB: Do you think this distance has anything to do with technology? A lot of the images are paintings of photographs of photographs. . . Do you think that kind of distance is necessary to be relevant in this age of images in general? We pay attention to photographs. We pay attention to things that are dissected and graphic, as you say. Do you think this quality is necessary to be relevant in this time or is it a quality that just developed as you were working? LT: Not necessarily. I know a great painter in China who stopped painting after that famous photograph was taken in Tiananmen Square because he didn't believe in photographs anymore. He was the first guy to make ten meter long paintings of displaced people working at a dam. But he went to the actual dam and painted the workers on the spot, and that was also a statement. It can go the other way around: how you actually apprehend your reality. And for some people that's always different, but what is certain is that you have a total abundance of imagery. AB: It seems as if there are also themes of horror and abuse that run through your work, as if you would like the public to fear what normally it finds acceptable. LT: I think that a lot of violence is hidden in the banality of what is existence itself. And this banality is not solid. There is also the filmic element. Anything lit in a certain way and positioned in a certain way can give an element of danger or can spell danger. Most of my imagery has the quality of the silence before the storm. It is sort of like an annunciation. It is never the endpoint. That is probably due to my own personal character and my education. I was raised by a mother who said that, "It's going pretty well now, but in thirty seconds, it could be pretty bad." (laughing) And I was also bullied in school like there was no tomorrow. From a very early age, physically and mentally, I was aware of all of those things, took them all into account. Of course, there is fear. If you're bullied as a kid, there is constant fear, because it can happen at any time. But you learn to attack in certain situations like that. You learn to keep low. And of course, it forms you as a person, because you will come back at those people. And I did. AB: What happened? LT: Well, nothing really crazy, but it forms strengths surrounding those occurrences in your life. It gives you the drive to prove things otherwise. The greater thing though is about this inner violence and a quite high suspicion of human nature, basically. . .which I think is healthy. AB: I feel as if this leads me to my next question because I want to talk about religion as a point of examination in your work. As well as fear. LT: Any form of nationalism or fundamentalism is, in my book, exceedingly dangerous. I did a whole series in '99 about Passion plays, but that was like turning religion into cosmetics. It was based on an old brochure of the actors in a production I saw with my parents in 1974. Yet in 1999, I never would have thought that we would yet again evolve into another era where fundamentalism in terms of religion would be so opposing each other as it is now, which means that religion is quite important. AB: Is there the examination of human practice or belief in this work? LT: There are many more images devoted to spiritual exercise, but I chose the more emblematic ones. I immediately thought of the color blue, the sort of blue that expands in a space. You first see the color and then the image. AB: Do you maintain a spiritual practice yourself? LT: Well, no. Are you asking me if I am a religious person? AB: Yes. LT: I have my takes from it. I have things that I feel I have to do out of compulsion, that have become ritual. Somewhere and somehow, I probably believe in something. I don't think of it necessarily in regards to religion, but more like the overarching feeling that you have to be careful. You have to stay sharp and open. There are stupid rituals, like the ones for each painting I make. I could easily buy enough paint to make three paintings, but no, I have to buy exactly enough paint for one particular painting. And then I have to go back to the shop to get another truckload of paint for the next piece. One at a time. AB: So not a God fearing existence. LT: No, it's more habit and maybe some kind of superstition. AB: Do different appropriative sources have different qualities visually? Like video still versus polaroid, etc? LT: Well once I know what I want to paint, then I will know how to paint it. The how is never first, always the what. Then everything is attached to that. AB: I am intrigued by the images in the other room, the Walt Disney inspired versus the Mormon inspired. Can you relate them to one another? LT: The Walt Disney series was right after the Jesuit series. My assistant found an image on the Walt Disney website that they were about to delete. It was the entrance of one attraction in Disneyland, an old photograph from the opening day where everything went wrong. It was the entrance of Alice In Wonderland. I thought that that was great, because it was also a symbol of utopia. The Jesuits also use the lure of utopic ideals yet still maintain a humanist aspect to their philosophies, but of course, with a hidden agenda. Now, here comes Walt Disney, who is a bigger than life character, who is utilizing the idea of fantasy, even making a park about fantasy. And of course, this man is a genius but also a control freak and something very scary in this controlling domain. I didn't want to make something about Mickey Mouse. I wanted to make something about this guy who had made a territory. That's why the title of the show was, "Forever, the Management of Magic." Disney saw himself as an entrepreneur, not an artist. Since he is such an icon, I thought that this was already a rather linear relationship, and yet a step beyond the ideal. AB: Those entities seem to very much relate to one another in terms of the grandiosity and brainwashing capable behind such utterly fantastic ideals. Fantastic relating to fantasy, not value. LT: They do indeed have all of these utopic elements in mind. AB: And then you have the image of the sea. LT: Yes, the sea, "Shore". It is an image which was made in preparation for a larger canvas which does exist. It has to do with my fascination with the border of the sea. From my hometown in Antwerp, it is a one hour and fifteen minute drive to the shore. As a kid, your first vacations are at the shore. There are white sand beaches and grey waves. The sea is a natural force. And it's also a natural barrier, especially at night. And that, I find, has quite a magical element to it. AB: You talk of borders and forces. .. The Kristalnacht image is something entirely different but depicts a forced boundary. Do these images relate to one another? LT: I think that a lot of the imagery that fascinates me is not only about boundaries but also about power. Not so much the having of power, but how power is organized. That probably has to do with how an image itself can hold power as well. AB: Do you write about your work at all while you are making it? LT: No, but there is a book distributed by MIT press called "On and By Luc Tuymans" which is comprised of texts and lectures of mine in the first half of the book and then texts about my work in the second half. AB: Do you see writing and painting as being very different things? LT: Absolutely. And I have to say that writing is more difficult. I wrote some decent things, I think. But it's such a pain in the ass because the idea of formulating ideas into eloquent sentences is SO difficult. . .I have a great respect for writers. AB: How does a body of work come into being? Is it visual or is it more of an impetus to convey an experience? LT: The very first impact is visual. It is an image that grabs me. The images usually have the characteristic of being either frightening or arresting and end up recurring. These are usually images that I don't understand at all, that I can only understand by making the body of work. This appeals to me as a challenge, a sort of symbolic puzzle, if you will. For example, this morning, I walked from the hotel all the way to the university campus, and I passed the Oregon Historical Society. I saw this incredibly strange wall painting on the back side of a building, the one with the trompe l'oeil and the scary figures and the cars. It was fantastic. This is the kind of image that will stick in my mind and begin another body of work, this absurd, human thing, that people pass by every day and not question. AB: You said that before you were making this work, you were making abstract paintings? LT: We all have to, that's one thing. I still remember the moment when I stopped doing that, which was in a painting class. AB: What happened? LT: I painted an SS officer, which created a massive amount of havoc. AB: Do you think there is an aspect of the abstract that you find necessary in these figurative works? LT: Well I must say that I don't think there is such a wide border between figuration and abstraction. I mean, without the Russian icon, Malevich would not have had this type of imagery to begin with, or even this type of thinking, which is very much about the subliminal. Malevich's work is also still quite religious to a point. AB: Because that, your own history, is real. LT: Yes, and I think art comes out of reality. Even Rothko. Many people may deny it, but it's true. So I don't see the distinction between abstraction and figuration. People may make the distinction and turn it into a style or an ism, but those are distinctions made by critics, never by artists. People like Rothko loved Edward Hopper. Unfortunately, Edward Hopper was such a conservative asshole, that he couldn't half understand that Rothko was interesting. AB: When you think of the future of painting, do you think of criticism having the same role that it once had in terms of isms or movements? LT: The important thing with painting is that it is still very much something that people want to see and experience. In one day, my show in the states will accumulate I don't know how many visitors. When it got home to Brussels, in three months, it accumulated close to 90,000 people, which is the same amount as a Lucas Cranach exhibition. This shows you what the impact is. Although there are all these different techniques, and even though painting might not be in the center of the mother of invention, in the periphery, it is even more powerful. AB: Do you think that when we discuss these topics, they are mainly for a Western audience? LT: I undeniably come from Europe. I am undeniably a part of Western culture. I am not ashamed of it. It is simply what I am. So, sure, of course. There is a different way of looking and making in say, the Maori culture of New Zealand, than that of Western Europe. There is a different visual language, a different apprehension of visual symbols. However, there are also red lines that connect different cultures. Even the cave paintings in Lascaux are included in this, which were long thought of as being only for the initiated to become educated in hunting. It goes further than thinking of the educational or instrumentalized imagery that is passed out; it is really an experience, and that experience is similar in any visual language. AB: Do you ever see images as being off limits? LT: Of course, yes. Then again, these flowers here. . I would have never had the instigation to paint these flowers ten years ago. I would have thought it ridiculous. And the one beautiful thing about painting is that you can’t go back. You can't go back. I could easily repaint what I painted in the past, but it would be totally dead. It would be without intention and repetitious. AB: What is your advice to students about being painters? LT: Art, I think, is very very difficult, because it's incredibly subjective. I know a couple of things and can advise people only in a constructive way, not in a negative or judgmental way. As a teacher, you must always look for the opportunity for this constructive advice. Sometimes, this is very difficult, because things are just bad and people are not gifted, and you should prepare them for that type of disillusion. AB: Do you think there is a place for published criticism in the art world right now? LT: There is high need for it. The people that still do look, and the people that try to comprehend and understand are older than me. I am referring to guys like TJ Clark and Hans Belting. TJ Clark is in his late sixties; Belting is surely in his seventies. Gottfried Boehm is another one of these people who is also close to seventy. .These types of figures are the only ones, strangely enough, who I consider authorities. There are some younger people too, but I don't see how they will exist with the same stamina or influence. There was this one guy in New York who wrote an amazing essay on my work, a brilliant guy, but he just gave up. A lot of these young scholars don’t get the follow up they need. They become academics or something, and maybe that is not totally uninteresting, but most of them are swallowed by a network that is dealing with its own discursiveness, and that discursiveness is fully based on the sociology of the eighties, in which we don't live any more. And then you get this whole facet of art making: lots of images adapted to concepts on paper which no longer have any consideration in terms of their visual impact. And the same goes for curators. Just a couple days ago, my very good friend, Jan Hoet, died. He was in the camp of Arnold Sellman, Kasper Koenig (who is still alive), these sort of lonely, at the top curators who decided very individually what they were going to do and what they liked and what they didn’t like. They had a vision. That era is over. AB: Why? LT: Because we have become so extremely democratic. Everything has to be explained. Everything has to be incarcerated in whatever. Then you just totally kill every pleasure. You totally organize everything to death. What is left? That is actually not what the people want. AB: Yet, it seems that the general public has some sort of need for this. LT: I think that it was a need that was created in terms that they were totally and constantly underestimated. Which I think is a very foul thing to do. One should never over or underestimate circumstances nor people. This is truth. AB: And it's condescending. LT: Yes, it is condescending, and then it creates an educational system that is ludicrous. Let them look. The biggest compliment you can get as an artist, is a little kid, seven years old, who saw your show in the Tate Modern and was so shocked by it, that when you are in the bar years after the fact, the little kid makes you a drawing and brings it to you. That is what it's about. That’s what it's about. And the rest is bullshit. Posted by Amy Bernstein on June 02, 2014 at 10:18 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |