|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Interview with Dana Schutz and Ryan Johnson Last November, I sat down with the Brooklyn based, internationally renowned,

figurative painter Dana Schutz and mixed media sculptor Ryan Johnson before

their joint lecture for the Oregon College of Art and Craft's Connection Lecture

Series . We spent an hour talking about their visit to Portland, exploring what

motivates each of their distinctive practices, as well as their mutual understanding

as individual artists (married to each other) as well as the professional skills

necessary to navigate a career as working artists.

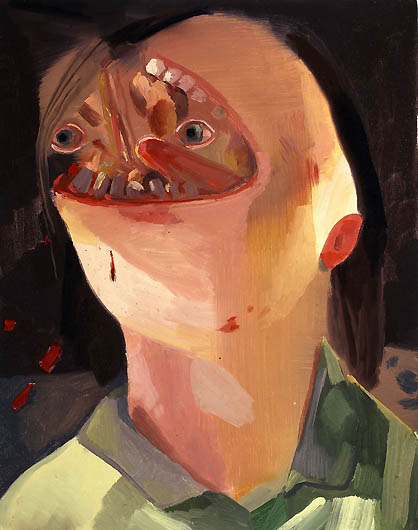

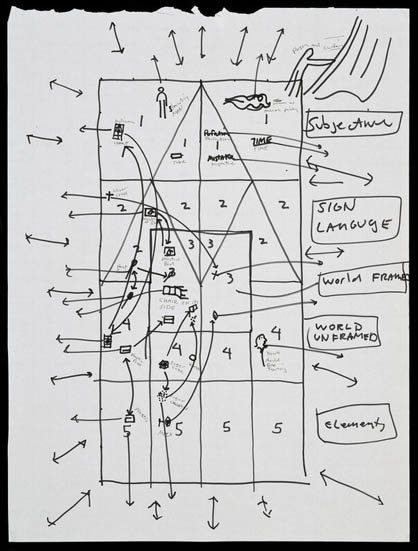

Ryan Johnson and Dana Schutz (photo Victor Maldonado) Victor Maldonado: Thank you Dana and Ryan for joining me today. I know you're both pretty tired having flown in from Berlin. When did you get into town? Dana Schutz: We got in yesterday evening. VM: Wow, that's not much time to enjoy the friendly confines and the beautiful weather. DS: It's so beautiful here. I'm struck by how it smells really fresh. We just went to the bookstore... Ryan Johnson: Powell's. DS: Powell's bookstore, which is amazing. Insane! VM: What rooms did you get to explore around Powell's? DS: We went to the art section. VM: The Pearl Room? DS: Yeah. RJ: Some good biographies. DS: Yeah, Ryan got a lot of books. RJ: We heard some interesting... DS: Intercom... RJ: Intercom action about a lost bandanna that was very Portlandia. DS: I know, it made us so happy. VM: If that show wasn't so true it wouldn't be so funny. So besides Powell's what else have you gotten to do? DS: Last night we went to an Italian Restaurant... RJ: And then we went to bed. VM: Perfect. What else is there to do? Well that leads me to some questions I have about both of your creative practices. I want to dig in and understand what values motivate each of your respective practices. I'll throw some questions out there to get started. Feel free to start anywhere. In a general way what motivates you? What gets you in the studio? What gets you making? I'd love to hear about any artists that inspire each of you? Where are you looking? What are the different ways of handling your work? What is it that you are hoping to activate? What do you want to express or even to change the operation of? How did you two meet each other?  Ryan Johnson, Pedestrian (2007) Courtesy of the artist and Suzanne Geiss Company, New York RJ: Dana and I met in graduate school. She was on my admissions committee, actually. DS: I thought he was depressed. I mean, I loved his work before his interview. I remember Ryan walking in after lunch. Sometimes Ryan does this thing where he breathes, which sounds more like a sigh, but he's actually trying not to pass out. I know that now, but back then I thought he was completely depressed. I remember I asked him a question about his paintings and then he sighed like he was really bummed.  Dana Schutz, Face Eater (2004) Courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York RJ: I mean, I think I really was depressed at that time. I wish someone had told me, "Oh hey, this is admissions, you only get one shot, so...try to present yourself in the best possible light and be excited." And I was just like, "Here's my slides, like, you know." DS: No! You were great. It was just that sigh. The sigh sounded like... RJ: I don't think I came off that well, but it all worked out. VM: That's a lot of pressure, when you're going through the interview process. Did you know Dana's work already? RJ: No, I didn't. VM: So, you just knew she was second year? RJ: Yeah. VM: And, Dana, you just knew Ryan's work from his portfolio you were looking at? DS: Yeah, and I thought his work was really funny... the way the subject matter seemed to point to a reality outside of the paintings. They were self-referential but at the same time not dry. They were really, really funny paintings. VM: Ryan, do you remember what you submitted that Dana is responding to? RJ: Yeah. It was mostly work from my senior year at Pratt. I was trying to make the most straightforward paintings possible, simple, everyday subject matter painted in flat areas of color. The figures were usually in strict profile and there was no perspective or shading. I don't think I saw the humor in those paintings then, but now I can appreciate it. But after undergrad I made a conscious decision not to make that work. When I got into Columbia I was like, "I'm not making that work. I'm comfortable making that work and I want to try something totally different." It was necessary for me to start over. Of course now, looking back, I don't really like the paintings I made in grad school. I like the work I made in undergrad. DS: I liked your graduate school work, too. He started making oval canvases, which was a big tip-off that you wanted to make sculpture. RJ: Yeah, I mean, I think that was the thing. By the end of grad school I was making sculpture. And then after grad school that's all I wanted to do. VM: So you'd gotten to a point where you really saw painting as a kind of semantic exercise? Using the sincerity of the object, the flat plane, the sizes, the size of things, a dry sense of humor about the painting's surface. Moving away from painting as a picture plane to painting as an object. RJ: That's exactly the move. I didn't know what to do with the ground part of figure/ground. Painting is so great at inventing space and I wasn't so interested in inventing space. VM: So since graduating do you feel your work has been focused not on this pictorial space but on a space that allures you and that calls you in is that a physiological space?

Ryan Johnson Cart, Red (2006) Courtesy of the artist and Suzanne Geiss Company, New York RJ: I have no idea. I've done a lot of different kinds of work since grad school. Some I'm not too into and some I like...but making sculpture felt natural and really exciting for me, much more so than painting. Even though I love painting. I look at painting now as much as I look at sculpture. I did both in undergrad. I applied with painting to Columbia, so I felt like I should make paintings. VM: I find that most artists are more dexterous than the public persona they portray. I think the work emerges from a much deeper and richer palette of values and then by the end when I get to read about it...it is cooked down. So I think there is a real value to know that it was neither painting or sculpture but that you had these two skill sets. A lot of times not settling was a symptom of this. And that not utilizing both of the skill sets was evidence of not being satisfied with the work. RJ: That's right. VM: Dana, what about you? Did you always want to be a painter? DS: Yes, for the most part, but in undergrad there was a short moment where I thought I could be a sculptor. Back then I was making paintings that were more sculptural-like relief objects made out of oil paint. Usually they were symmetrical and personified, resembling something like a face. They would have indexical indentations and gouges that seemed like orifices. I was also painting terrariums and subjects that alluded to objects as well as pictures. I was always interested in that kind of objecthood and probably still am in a way, as I'm always conscious of the framing edge. Early on, in art school, I didn't feel comfortable with subjective pictorial space. Maybe it felt too open, but I feel completely differently about it now. To make a picture can be radical and there is the feeling that anything can happen, at least when you are first beginning a painting. VM: There is an excitement. There is a feeling. DS: Yeah. VM: Especially in front of that empty canvas? DS: That is always exciting, although as you go along the painting has its own logic, so your choices do become more limited. VM: Both of you give us a lot to be critical of... A lot to engage with our senses. There is the temporal, metaphysical, psychological space of the picture but then there is also the tactile space of the material that is in front of us that has a pressure on us. Walk me through a scenario of making. What motivates you to start making new work and what are the values that drive it forward? DS: It begins with a very open process. I'll really entertain anything, but some subjects seem stickier to me and they can open up into larger issues than what they initially present. With those ideas it usually begins with a question, "If this were to be a painting, how would it be?" I'll draw thumbnail sketches beforehand just to figure out the structure, and in the act of painting there is usually a lot of back and forth. Recently, I have been wiping off areas, trying to work the whole painting wet into wet. I've been really interested in each gesture registering, to have its own kind of space and energy to it. I'll know that its done when it feels like an itch that stops itching. VM: What a great metaphor. You feel it? DS: Yes-it is a feeling. It is very physical. By the time I start a painting I'll have an image in mind. Whether it's a problem or something more basic... it is often like, "I want to see this thing painted," and it goes from there.  Matt Mullican, Untitled (2004) RJ: You also use language a lot, too. Dana writes lists all the time. It's like you picked up that great Matt Mullican book at Powell's and was just like, "Wow, these are really startling sentences, poetic sentences, that you can interpret in a lot of different ways." DS: I like the simplicity of those lists...a very simple sentence that could spark an image. I think Bruce Nauman does that. Sometimes the subjects come from language. An image could start with a verb or a phrase. I made a painting recently of people assembling an octopus and it may have just started with even the word assembling. It had all these s-type forms in it. It started to make imagery and even began to inspire a narrative situation and structure the piece.  Dana Schutz, Assembling an Octopus (2013) Courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York VM: It's amazing that even just the word assembling could inspire the notion that the word could be a kind of animal. DS: Yeah. RJ: Yeah, yeah. VM: Like you were saying, getting to the simple sensory experience of repeating a word so many times you forget what it means and then you forget how to pronounce it. And then all of a sudden there is magic. And it seems like there is a lot of putting on and working through. What about you, Ryan? RJ: In terms of generating ideas it almost always starts with drawing. I do a lot of thumbnail sketches and put them up on my wall and the ones I keep going back to are the ideas I know I should try to make. The thumbnails never show exactly how the piece would look, though. The best-case scenario is when the idea and the making of the idea kind of happen together. I feel like I am getting better at recognizing the ideas that will hold my interest the longest, the ones that stick with you. In the end you're trying to surprise yourself. VM: I know that your studio practice can be compulsive. Things that you know how to do well, tricks, the trade, so the surprise you're talking about seems to draw a lot of artists back into the studio. There are a lot of "knowns." A lot of things you do know. But it seems to me that what is going on is that there is an idea that you might not think at first as being very sticky is drawing you back into the studio. Is that a common occurrence or is that something new in your work? RJ: It's always been there. I mean I think it is more likely to happen leading up to a show because you have a different mind-set when you're on a deadline. You have to trust yourself and let things move very quickly. You're almost disassociating, just trying to make the work. Oftentimes you don't know why you made the moves you did until after a show has been up for a few weeks. VM: So much of what I feel is motivating you, in different ways, is the work ethic. How each of these disciplines gives you a manner of abiding. Not confirming your biases and also not prejudging an idea before it is fully cooked is that something innate that you brought to the table or is that something that each of you garnered in your educations? Or, is a combination of the two? DS: It's something that just feels good. You feel like you want to be working. If you're not, you feel off. We've been traveling a lot recently and I started feeling a little antsy.  Ryan Johnson, Rocking Horse (2012) Courtesy of the artist and Suzanne Geiss Company, New York RJ: I feel like it is such a mental exercise in a way. The big picture, the most important battle, in terms of getting better as an artist and challenging yourself to get into new territory happens in your head. I can understand now why so much of the work I'm attracted to is people's later work because I imagine you really do get better at making, at navigating... DS: Your own habits? RJ: It's all about contradictions. On one hand you have to be super confident and on the other hand you have to be your own harshest critic. Being an artist means holding these contradictions in your head but still being able to operate. DS: Right. RJ: And, it's such a fine line. DS: And sometimes it's not natural. Nothing feels right and you don't feel like working. Sometimes it's like, "Okay, don't stop until these five cds are done playing," and you just work until something catches. And even if nothing does, the process can lead to something else, and at least you've gotten into the headspace of making. Then there are times when you actually do have to get out of the studio and go for a walk, you know? VM: It seems to be a balance. I think that's why I was interested in. Not only this value of the work ethic. Generally, I think, both of you being interested in making and it making you in a way as well. But beyond that I think what I hear about you can't get out of the studio until all the cd's are done speaks of a discipline. So balancing that work ethic that maybe is generative, maybe humorous, maybe not. Maybe it serious. On the other hand that discipline of not letting an idea that is not that good and not giving up on it. How else do you find balance in your lives? Being married to another artist you're probably always going to each other's shows and openings and I'm sure you also have friends who are artists who also have openings. How do you balance the work of being in your studio but then going out and being omnivores of your life, gathering inspiration, what is that inspiration? Are you guys pointing? I mean, I'm sure you're pointing out things for each other all the time. Tell me a little more about the balance that you strive for in your life or that you have already? DS: I think it's pretty great. It's nice being with another artist because they understand the need to be in the studio, and we tend to have a lot of the same interests. There is this idea that you should have hobbies. Sometimes it's natural; you'll want to do other things, but making work-it's what we really enjoy. And we like seeing shows and going to museums. RJ: Our lives are pretty art heavy, but that's how we want it. DS: We watch DVDs at night. Okay, now this is sounding pretty sad. VM: I don't think you're alone. DS: But then there's moments when I think that we should start cooking. Something besides spaghetti, something that's normal, that's healthy. I'll think, "We should get a juicer and start juicing. Let's juice our breakfast." But that's more me... that's not you. You're always like, "No, I'll just have spaghetti." We usually fall back into a natural rhythm. We tend to wake up late but work in the studio until late. There are a lot of artists in our neighborhood, and we'll go out to dinner with them often. RJ: There's a community. I feel like it's easy to underestimate the importance of being part of a community when you're an artist. Being able to have studio visits with each other whenever you need it. We definitely have that. VM: Where do you live now? Is it a live/work space? RJ: In Gowanus, south Brooklyn. We each have our own studios and we live a couple blocks away. VM: That's pretty great. Talk to me about community because it seems like it helps you find a balance because it doesn't seem like either of you have one size fits all answers. It seems to be granular and in the moment. Does your community help you cater to some of that balance? RJ: Definitely. After grad school, a bunch of us built out studios in a raw eleven- thousand-square-foot space in Gowanus, so we kind of had an instant community. And we've been in that space for eight years, and just a couple of years ago Dana got a new space a few blocks away. It is a bit bigger and a bit better of a space. DS: I love that space. RJ: Yeah. In the new space it's just more obvious where the painting wall should be. DS: Yeah, I had a hard time in the other space. There were windows and I kept on blocking them up. Which was weird. It was an off situation. But there is a great group of artists in that building. Having a social community right there was amazing. You didn't have to leave the studio to socialize, and in that way it was really fluid. Everyone there is really funny, too. RJ: You get so much out of those conversations. Even passing people in the hallway and briefly talking about shows that are up or bouncing an idea off of someone. I mean, that kind of conversation is different from a full-on critique, but you get a lot out of it. DS: People would ask, "Have you seen this show?" or say, "You should read this thing." VM: It seems that so much of the benefit of going to a place like Columbia, or any great art school, is that you understand the importance of a support system around you. You talk about your shared interests but also having each other, that village around you. Is that something that you brought with you to grad school or is that something that you picked up before school? RJ: I think we got lucky. It was an amazing group that we were there with so I think we just wanted to maintain that feeling, and it is also, on a practical level, much cheaper to rent a large space and then divide it up. DS: I went to undergrad in Cleveland, and there was a really good community. I think after undergrad people tend to scatter. Some people went to the West Coast, some people stayed in the Midwest, or some people 0went to Germany. In New York, after Columbia, life felt easier, partly because most of our friends stayed there. VM: As both of your careers gather more acclaim and grow more successful is it more difficult for you to receive the critical feedback that you're after, sincere, candid, critical feedback that really pushes your work or do you find that people are willing to speak truth to the work? RJ: Well, I think that one of the benefits of having a group like the one we do in Gowanus is that we've been close friends since 2001. And we all understand that the career thing is a separate conversation from art; they are two different animals. You can be a great artist and have a great career or you can be a great artist with no career or you can have a great career and be not such a great artist. The two are not connected necessarily. VM: What about you Dana, do you feel the same? DS: Definitely. A lot of people we know are also teaching, so they are in touch with new information from a younger generation. But I also think that there's a certain point when you feel like you don't want feedback. You feel connected to what you are doing and you just need to work through it. There was a time when I was asking everyone their opinion in the building, and it was getting nuts. Now I'm working alone and it feels really good. I do still ask for Ryan's and a couple friends' opinions, but less frequently now. VM: Do either of you have any assistants that help you do what you do? DS: I have an assistant who helps organize things...? VM: Which is important, right? RJ: Anthony is great. DS: Yeah, and he also helps clean brushes, which is huge, because I use a lot of brushes and they can really pile up. VM: It’s interesting because so much of what you’re talking about is the work of getting to work. The work of separating the studio practice from the career and then just the logistics of having to tend to those things. If we could begin to end things by talking about how you keep this balance that you talk about, how you learn to separate the careerism that can go along with being a successful artist, that not everybody affords, and when you just need to shut the world out of your studio to work through an idea. Do either of you feel pressure to open up at a time when the work isn’t where you want it to? Both of your work is in demand how do you upset someone and keep them out of your studio? How do you manage that career in a way that feels feasible to you?0 DS: You just keep them separate. But collectors usually don't come to the studio. I think there are moments when you do want feedback and when it is okay to have people come by the studio, like student groups. RJ: Unless it's right before a show... DS: Yeah, right before a show it's usually so hectic that you can't have anyone come by. Then headspace is really important, and you can feel so fragile that you don't want any kind of feedback unless it's from friends or other artists. Anything can throw you. RJ: Studio visits are bizarre. DS: They're so weird. RJ: Because if it's not a friend and it's a class or a group of some kind, they can visit your studio for fifteen minutes, and then you feel like you have to go on a walk for an hour just to clear your head. VM: It is such a private space it feels like an intrusion? RJ: It's like I always forget that somehow.. .you can't just get straight back to work after a studio visit. VM: So for you Ryan that buffer zone is making sure you don’t step straight from one space into the other? So there are business meetings or business visits and separating them by having another activity to prepare your self mentally? This seem like professional practice skills that you have to learn along the way did either of you have mentors that you really turned to in your life not only for making work that you were excited about but also not getting in your own way as a business person? RJ: I think everyone figures it out. I mean, I remember visiting the studio of one of my professors when I was going to Pratt Institute. Just seeing his studio was really eye opening as I realized that there is no one way to set up a studio. It’s just about figuring out what works for you. DS: I learned a lot from peers, mostly at Columbia. There were some students who were definitely savvier than I was. I remember trying to send these paintings off to California by packing them in a giant refrigerator box filled with Bubble Wrap or pillows-- I don't know what else was in there. That's just how I thought you packed art. It was basically a boulder of cardboard and duct tape. But then I met Ryan, who knew how to handle art, and I saw how it should be done. RJ: I remember one time you took a painting to a gallery on the subway with nothing around it, and the gallery was like, "How did you get this here?" And we said, "On the subway." And they were like, "You didn't put anything around it?" DS: Yeah, I don't know. We put ourselves around it. RJ: We were paying attention and it worked out fine, but we never did that again. DS: Most of it we just learned by making mistakes or from other artists. Having community was its own kind of survival system. You had a support system that was made of your peers, and that turns out to be more powerful. At that age, all the professional stuff can feel alienating. But organizing shows with your friends, working around them, sharing information can make it feel more manageable and fun. There is a momentum to a group that shares similar interests and are of the same generation. You'd go to a friend's show because you wanted to, or visit a gallery because you liked the group of artists or the feeling there. It didn't feel like networking because it was what you would do anyway. RJ: It's rooted in the art. DS: It's rooted in the art, and I think people grow together. VM: It can get creepy very fast and alienating very quickly especially when success enters into it, right? DS: Yeah, but artists are always sharing information. Someone can say, "That guy's a creep," and another, "Yeah-that guy is a creep." And then you're like, "God, okay." VM: "I'm not alone." DS: Right. VM: Besides having each other and this community that is so stimulating to your studio practice that gets you in and out all the time what kinds of inspiration are you drawing from art history, if at all, specifically in the works you're doing currently or in the recent past that are really driving you forward and making you ask questions anew about your work? DS: In terms of art history? VM: Yeah, because when see your work, artists like James Ensor, who had this wonderful paint handling and almost a creepy and absurd sense of humor... it echos in your canvases? DS: Yeah, Ensor is incredible. It changes all the time.... I have been looking at Milton Avery recently, mainly because of his really nice palettes. But I think it's intuitive... what you need, or what looks good, or what feels good at that time. RJ: That's kind of a big thing when we were getting out of undergrad, when we first met we were talking about painting issues and where we thought painting was at and the importance of having an intuitive relationship with art history versus a referential one. DS: That intimacy is also closer to how people read art. When you're in front of a painting it's a very diffuse experience, so you can look at one part and it can set off a stream of associations. The reading can be particular and aberrant even with an iconic, canonized piece. While making a painting, you can have a literacy of images and use them almost like a material. The act of making can lead to something really unexpected. You could be like, "This part reminds me of the feeling that this other painting has." If it works for the subject and the logic of the painting, then I think it can be kept. RJ: That's the thing... it has to support the subject. VM: Are either of you teaching right now? DS: I'm teaching at Columbia. I love it. I have this group of fifteen graduate students. Basically, we meet one week each semester and do whatever we feel like doing. We see shows around the city, take field trips, invite speakers, and there are studio visits. It's really fun for me to see what they are doing. VM: So what drew you to OCAC? What made you say yes to deliver this lecture at the Portland Art Museum? DS: We were just excited to visit Portland. RJ: Yeah. DS: I had never visited the school, but I had visited Portland once before and had a really good time, so I thought this would be great. VM: When were you here before? DS: 2004. VM: Wow, so it's been almost ten years? RJ: That's wild. VM: I bet things haven't changed at all since you were here. DS: Yeah, today we were driving and I thought, “Hey, that is where I got coffee ten years ago.” But it was a very brief visit. RJ: I remember a lot of people we knew moving to Portland around 2000 and knowing there was a great music scene and a lot of artists moving there, so I've been curious about the city for a while. VM: Do you two have a sense of what you're going to talk about in your lecture? RJ: I'm going to go through my work more or less chronologically. I mean, I'm taking some stuff out, obviously. At Columbia we had a lot of people come through to give artist talks and I found it so useful when an artist would just go through and explain what they were thinking about when they made certain works.  Dana Schutz, Swimming, Smoking, Crying (2009) Courtesy of the artist and Petzel, New York DS: I'll be talking about my work. I keep on thinking I should speak about something else. But the relationship is always changing with my past work, so it can feel new. VM: But, your attitude about the work can change? Like Ryan was saying watching all those slide shows you realize that artists change their mind about their work all the time. Give me a sense of what the next six months to a year look like for each of you. DS: We will be teaching at the Atlantic Center for the Arts, a residency in Florida. And then I have a project at the ADAA fair in New York this March. I'm making only drawings for the booth, which is new for me. RJ: I'm just doing some group shows in December and then in January I have another group show. And then I'll start figuring out the next solo show, which will probably be over a year away. VM: Is that typical of how long you have to prepare? RJ: Usually, it's more like a year and a half. But there's no set date. DS: It's usually about a year. RJ: You're faster than me. VM: What are the questions in your work right now? What are the questions that you're asking the work you're looking at? RJ: I mean, I feel like it always works like a pendulum. It depends on the last thing you did and a lot of times you end up going the other way. Like, if the last show I did was a full installation, then I might find myself wanting to pare things down for the next one. It's always an evolving situation. Which is why I think it's so important to keep showing your work. Even if it is just setting up a show in your studio and inviting friends over. Showing changes the relationship you have with your work, you can see it from a different point of view, and you can move on to the next thing quicker. VM: So this pendulum swing is constant for you? It always seems that both of you are always questioning the material. DS: I agree with Ryan. It's true that I usually want to make something in response to the last painting I made. Recently, I've been interested in that space directly in front of the canvas and the exchange between the subject and a viewer. I have just finished a series of paintings that are very large and vertical, but now I would like to make works much closer to my own physical scale, and I'm thinking of subjects that engage a more local exchange. I've been thinking about people in bed, maybe because I have been so tired lately! But a bed is a very specific, soft space that can possibly mirror the canvas. You can drag anything into it. 0 VM: One of my favorite paintings is by Laura Owens of a couple in bed... DS: Oh, it's a great painting... VM: She painted it beautifully. I remember walking up to it when I was a grad student at SAIC and she was having a solo show at the Milwaukee Art Museum and I walked up to it and said to myself, "That's the biggest coziest paintings I've ever seen." I realized how bad ass she was. She had great handling of the material. I could tell she was alive with the material. Not to pigeon hole you but there seems to be that spirit in both of your work, too. Of being alive in the work and trying to make the work that brings your skill set out but also challenges you. RJ: I think subject matter is so important. That's the thing I have really been focusing on for the last year and a half... trying to put my life in my work. VM: If it is something that matters to you, you’re more adept at it, more patient with it, or, like that idea that you’re not quite sure about. And if it’s something not close to you it is somehow easier to let go of? RJ: Yeah, I think you have to make work about things that really matter to you because those subjects will have traction. It may sound clichéd, but I think it is important to put as much of yourself in the work as possible. DS: I think there's a kind of impulse and urgency to make a work that feels like it needs to exist. To add a physical thing into the world, something that has consequence, is a big deal, especially in a time in which we are bombarded by so many ephemeral images. The making and contemplating of a painting is much slower than how images typically circulate. Not that paintings can't circulate, but I think they can have this double life. VM: Especially, after the middle of the last century, with the dehumanization of the picture plane, when there wasn’t enough room in art for our human follies? Human concerns are for the news and advertising... not art. Both of you seem interested in letting it be part of the conversation and dialog, what we scrutinize. I’m always being surrounded and bombarded with images that are made very far away from me and getting to that local or even that communal experience that you bring up... that cult exchange is so rare. That seems to really be very necessary for independent, thriving activity. I tend to agree with both of you. I think you’re coming from different points of view though. Interviewing you both at the same time I keep trying to find correlations, but both of you think very differently about what you each do. DS: Well... I do mostly agree with Ryan. RJ: We do. But I think both of us are very idea-based. I realized this recently. I don't really start a piece until there is an idea. I can't work in series. I have to be really excited about the potential of a new idea being brought to light with each sculpture. I can't just start on formal grounds or on materials or style. I don't care about those things. Those things can't make me start a piece. Posted by Victor Maldonado on May 23, 2014 at 18:51 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |