|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

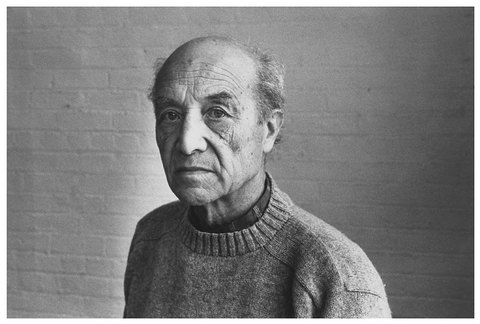

Interview with Matt Kirsch, Associate Curator of the Isamu Noguchi Museum

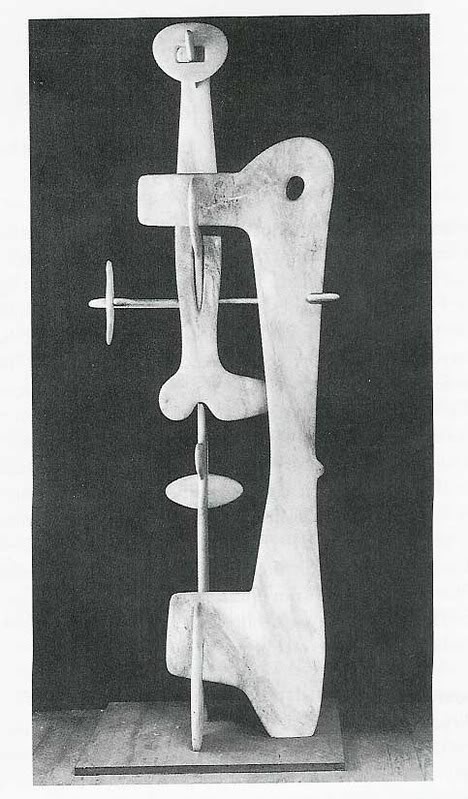

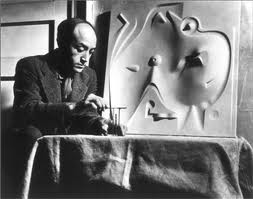

A: I wanted to ask you first a bit about your background as a curator. How did you begin your curating career? MK: I got a master's degree in art history from Temple University. I had lived in New York before that, and then I came immediately back to New York after that and ended up working in galleries for about five years. I did everything from installing shows to writing press releases. At a certain point I realized that I didn't want to own my own gallery, so I went back to school for an advanced certificate in museum studies at NYU. The director of museum studies at NYU was my advisor and also happened to be the former director of the Noguchi museum, back in the nineties. I met with the then curator, and we got along very well. It was a nice, easy transition. I have been with the Noguchi Museum for almost six years now. A: When you worked in galleries was the work exhibited contemporary? MK: For the most part, yes. The George Adams gallery's program was probably three fourths contemporary, and then once in a while there would be a show of an artist that he had absorbed from the Allan Frumkin Gallery, of which his gallery was an extension. So there was an occasional exhibition of work from the sixties and seventies, but it was contemporary for the most part. A: What do you think of the arc of the curator's role as you moved from dealing with exhibitions of contemporary work that changed every month to the Noguchi Museum, an institution solely dedicated to one artist? Do you feel like more of a conduit for the artist's work or more of a creative voice for the exhibition? MK: Well, I think this is pretty self effacing, but I don't really see myself as a pure curator working at Noguchi. Obviously our mission is to show the best of one artist and take advantage of the resources that were left behind by that artist. One floor of the museum and another entire gallery are pretty much how he left them installed when he died. We try to honor that. For me, it is almost like working as a researcher, just getting to know the work and finding associations within the work. Sometimes I get to promote work that I like and have seen in storage and really hasn't been seen that often. So, it's a different kind of curating. AB: So what is the real difference between working for an institution solely dedicated to one artist as opposed to having a continuously shifting roster of work and artists? I read on the museum's website that sometimes it takes years to realize exhibitions. You're almost like an architect of exhibitions, so to speak. MK: Our museum is slightly different. In the past, we've worked with guest curators, and we're always actively encouraging scholarship in Noguchi. Occasionally a curator will approach us with an idea for a show. And I will work with them to not only find works within our collection that fit within the parameters of the idea for the show they envision but also point them in the direction of private collections that have Noguchi's work. AB: Had you always followed Noguchi's work? MK: I probably had the same understanding of him that most twentieth century master's art history students have before working at the museum. I knew a handful of sculptures from visiting museums in New York, and I knew some of his public projects. But I really didn't know fully what he did. I didn't really know about his theater set design or some of his larger landscape projects. I really only knew public sculpture and "Kouros" at the MET and a couple of pieces at the MOMA. AB: The arc of his work is pretty amazing. MK: Sometimes it's nice to come in without any strong preferences or a strong understanding of an artist because you get to learn that much more about them. AB: Absolutely, and you bring such a fresh perspective. How do you see Noguchi's life's work in the context of the contemporary art world? MK: I feel that Noguchi was very ambitious very early on in his career, and some of his ideas were taken up much later and realized in a climate that he didn't have access to. I find that really amazing; he wasn't really tethered to the limited range that a lot of sculptors were in his generation. He was a very young sculptor in the 1920's, and he quickly realized that he wasn't interested in doing work for someone's home. It was hard to sell sculpture. It was harder then to find collectors. And he ended up storing his best work, and that is why we exist as a museum. It is amazing to see that he really anticipated a lot of the earthwork and landscape art of the sixties and seventies. AB: How do you think his work was influenced by history? MK: His mother was very well educated Bryn Mawr student and got him interested in mythology at a very young age. He was also exposed to Japanese culture from the age of two to thirteen. I think that he was able to draw a lot of inspiration from very disparate cultures and make connections between them. I mean, the fact that he became friends with Joseph Campbell. . . AB: I didn't know that. . . MK: I could imagine where the origins of their conversations would start because he was a voracious reader. I don't know how he had time to read, because he was always traveling or working. For some reason, India captivated him before he had even seen it; he had only known it through photographs. He spent a great deal of time there in 1949 or so and went back once or twice after that AB: What was Expo 70? MK: In Osaka, Expo 70 was one of the international exhibitions that popped up throughout the world in the twentieth century. And his friend, Kenzo Tan, I believe, did the design for the entire site. He asked Noguchi if he would contribute in some way, and instead of creating some sort of monumental sculpture, Noguchi became more interested in working with water. So he designed a series of five fountains within a large pond that were all automated, each with a unique spray patterns and applied technology in a way that a lot of people hadn't thought of. AB: Noguchi's ideas and intentions surrounding myth and the calm amidst chaos seem to be a recurring motivation in his work. Do you think the work still relays this even after his death? MK: I don't know. I think he was very interested in Jungian philosophy and imagery, and he was very well read in that. But I think we live in a very different era now where we have just absorbed that as culture, and I think that most people don't really take the time to read about it or explore what captivated so many artists not only like Noguchi, but anyone who was say doing automatist art. AB: In my reading about Noguchi, he really believed in the social significance of sculpture and the historicity of all sculptural monuments relating to each other. MK: Yeah, I think a lot of artists tried to produce works that had commonalities across different cultures, and I think that Noguchi, in particular, was a conduit for everything that he absorbed. I don't think there was a precise and intended result for each piece. And I believe his titles came after the fact. He was often just as surprised by the final product. There were pieces that were very intricately planned because they had to be. And he created paper models to figure out proportion and stability of what might be a small architectural piece. But especially during the last 25 years or so of his life, he was very open to a sculpture evolving. Sometimes a sculpture would take ten years to complete, and he would just step away from it and return to it to see if it had any deeper significance that was more immediate to him at that time. AB: I always consider that kind of artistic decision as being incredibly subversive.

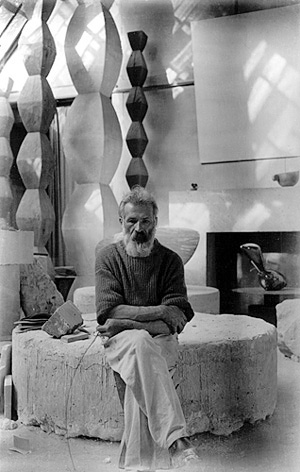

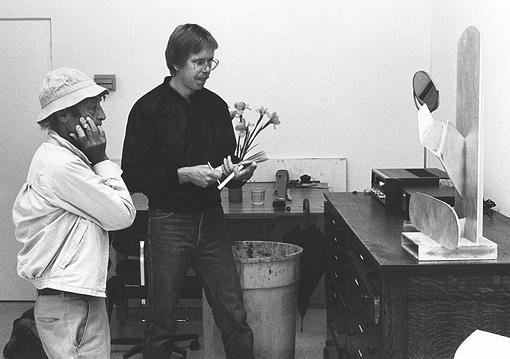

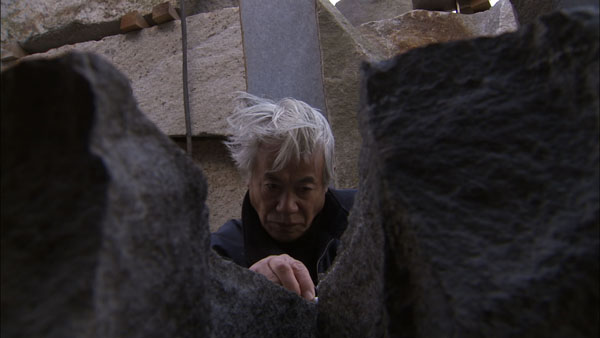

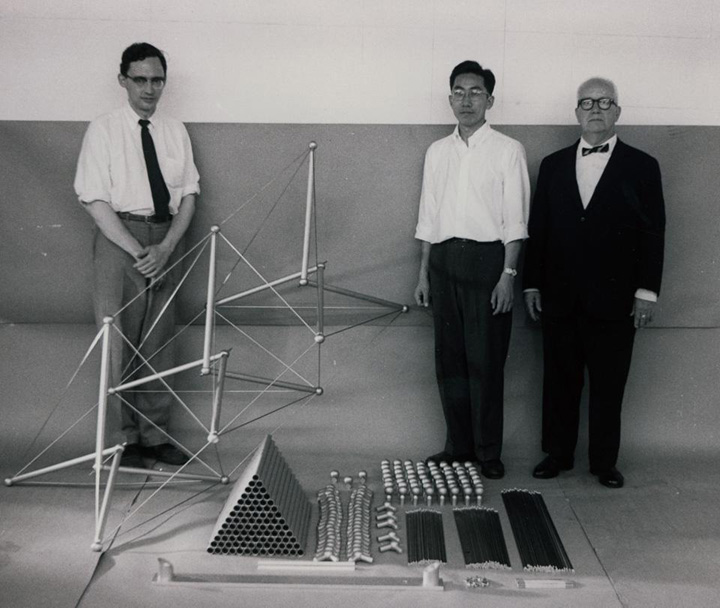

AB: It seems that Noguchi and Koons are coming from opposite ends of a spectrum of ideology. Noguchi's work seemed to be very much about his sort of spiritual self and his work living in a social space to inspire humans in a spiritual and intellectual way, whereas Koons is commenting on a culture in a very complex web of materialism and capitalism. But in the end, you have these enormous works that both become the products of an American experience and thus become the culture themselves. Do you know much about Noguchi's process? Like how a piece would begin to be realized? MK: I actually just curated a show called "Hammer, Chisel, Drill", which comes down very soon and is all about Noguchi's studio practice. Originally, we wanted to do a show exhibiting just Noguchi's tools, but we quickly realized that his best tools were pretty well dispersed throughout the world. What we had on site was just what had accumulated over time, just like his sculpture. In the end, I ended up concentrating on his five most productive studio periods in his life. During one of them, from 1969 until he died in '88, he kept a studio on the island of Shikoku, in Japan, which is now a museum on its own that we are distantly related to. At that point in his life, at the age of sixty-five, he had finally accrued a reputation in the world, designing gardens for UNESCO and major projects with architects in New York. But he came to Japan to do one sculpture, which is now in Seattle, and while he was there he met a stoneworker who was the youngest son of a family of stoneworkers in Japan. And they had an amazing rapport. And that is kind of the origin of the last part of his work: finally having access to some of the finest and hardest granites and basalts in the world through this family. AB: Was the stone from Japan? MK: Mostly from Japan. This family imported a lot of stone, but Noguchi prized Japanese stone over all others besides Greek and Italian marble, which he also liked quite a bit. But he had already spent a good ten years working with marble at that point, so the challenge had dissipated for him at that point. Marble is a soft stone, so he wanted a harder stone, but his age was a bit of a factor at that point, so this assistant, Masatoshi Izumi, helped him realize some of those ideas. It was an amazing collaboration because Izumi was basically the yard boss for a crew of other people. Noguchi oversaw this work fabricated by the team, and it allowed him to be incredibly productive. He enjoyed this immensely. He also had a deep philosophical attachment to stone, because he saw stone as the bones of the garden and the rest as the flesh. The flesh wears away but the stones are always there. He felt that stones were the link between humans on earth. MK: Many people that have written about Noguchi write about his not fitting in to either of the cultures of his birthright. He was born in Los Angeles but lived in Japan as a child and then returned to the US at the age of thirteen. So he was already living outside of that culture and then being reimmersed in it, having to try and catch up and become part of it. He had a very complicated relationship with his father who he never really was close with. He never really felt accepted in Japan until his return trip in 1950, and that was an acceptance by a group of younger, avant garde Japanese artists. So, he was still treated differently. He was kind of a wanderer. He never felt completely at home. AB: I mean as an artist, did he ever become disillusioned by art itself? MK: Yeah, I think pretty early on, which is what I think drove him to work outside the traditional modes of sculpture. I don't think he ever liked the idea of making work to have it be stored away in museum storage. He always enjoyed making sculpture, and that was a very personal thing, but I think he always wanted to be working on a grand project. AB: Do you think that was because he believed in the social significance of what he needed to do? Did he believe that industrial design or art had more social clout? MK: He really believed that sculpture could be anything. He liked certain materials, and there were meaningful associations with those materials. He always thought that stone was the best, but he wasn't afraid of working with aluminum or stainless steel. I think he really disregarded a lot of people's opinions on what could be art. In the 1930's he started working in industrial design, and he never separated that from his other work. He saw himself as a sculptor, and on a particular day, he was going to work on the housing for a baby monitor. Or next week he would endeavor to design a playground system that might work, and coming at it from different directions. He failed two or three separate times in attempting to make a playground made of earth. AB: Speaking of playgrounds, I know that those designs still exist. Does the Noguchi Museum ever consider actually having them built? MK: Part of the role of the foundation is to try and protect his ideas a little bit, and if it wasn't already in progress when he died, we cannot attempt it. There was a park in Sapporo, that Noguchi was working on with Shoji Sadao in the last year of his life. Sadao was an engineer and architect who really helped get a lot of Noguchi's ideas off the ground. He also worked with Buckminster Fuller as well. He was kind of like a shared staff member between the two. The city of Sapporo approached him to design this park, and Noguchi used the opportunity to create sort of an anthology of a lot of his ideas. Unfortunately, he died a year into the process. Shoji Sadao carried on the process and did his best, based on his experience in working with Noguchi, to remain true to how he would envision it. After that, we really shied away from trying to realize his projects. Occasionally, we'll make a model based on his ideas and using another fabricator, but it's really just to advance the study of Noguchi. If we take it upon ourselves to recreate something that he didn't do in his life, then that opens the door for other people coming to us and wanting to do it. We kind of have to protect his legacy in a way, as much as we would all love to see that playground. AB: In some of my research, I came across that particular playground that Noguchi had worked with Louis Kahn on to design. They collaborated on it for such a long time, six years wasn’t it? During that time, play was thought to be the birthplace of creativity. I think we need more of that type of environment in this country. MK: Oh, and how we wish we could build it, but there are so many hurdles. To have Noguchi's personality and attempting to charm some city official would be the asset required, but we're just one step removed. AB: That's so unfortunate!! Such a shame! I can barely stand it. What do you think was Noguchi's ideal experience for his viewer? MK: I think it comes back to an attitude he embraced from the beginning, which was to have the viewer bring his or her own self and assocations to it, to bring their own intellect to complete the work. In making his work, Noguchi often stood back until the very end. I think that is a very encouraging part of the process for the viewer as well. MK: I know he thought so. A lot of people approached him once he was a known figure to make commissioned projects. You know, they wanted a Noguchi for their courtyard. He didn't really want to give you a piece and let you do what you wanted with it. He would rather have the setting to work with as well. I think it was mostly because he understood space. He had an amazing grasp on how it worked, how if you offer the viewer many different options on how to enter a space, then their experience can change endlessly. AB: What are your hopes in terms of the way Portlanders receive this exhibition? MK: Well, I think it is a great setting to see his work. I worked with Diane Durston closely in selecting the work for this exhibition, and I think in the end, it was a fantastic collaboration. There was a very intuitive rapport in our conversations. We wanted to show both sides of the coin, but I think that a good deal of it is work that responds to the idea of natural materials and references landscape quite a bit. My ultimate hope is that it's a nice compliment to the garden. I hope it seems like an intuitive fit for the garden for people that might be visiting the garden without knowing that Noguchi is here and vice versa. I hope that Portlanders will visit the garden because they hear Noguchi is here. Posted by Amy Bernstein on May 03, 2013 at 10:19 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |