|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

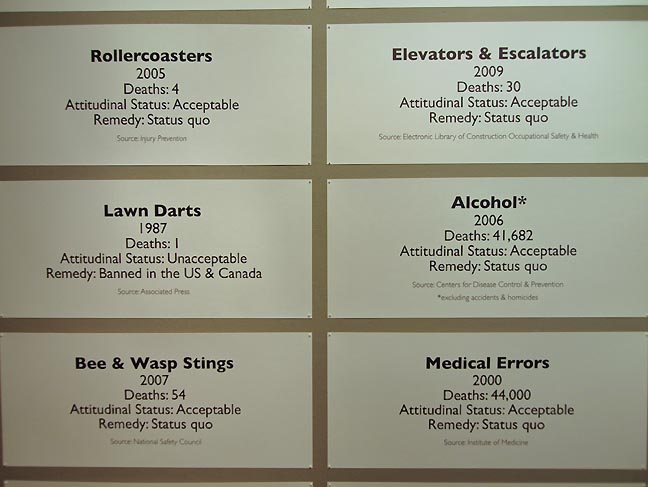

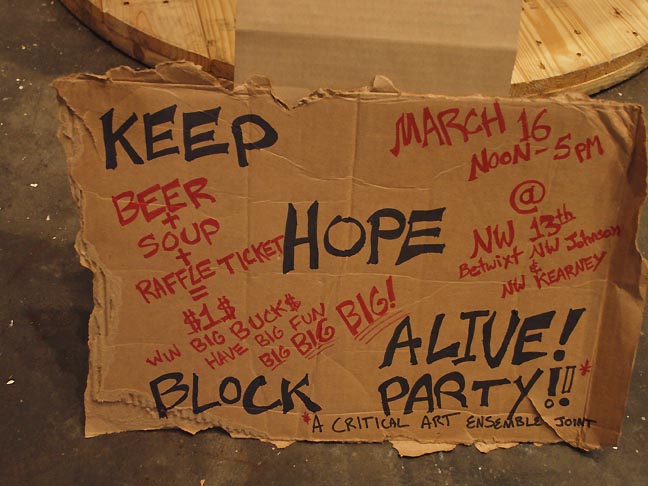

Interview with Critical Art Ensemble  Critical Art Ensemble's Acceptable Losses (detail) at PNCA's Feldman Gallery On March 15th around Noon, I spoke with Critical Art Ensemble members Steve Kurtz and Lucia Sommer. Tori Abernathy: You've been in the planning stages for Acceptable Losses over the past four years now, but the show seems strangely appropriate in light of recent happenings. What led to focusing on themes of death and suicide in this location, Portland, or in the Feldman Gallery? Steve Kurtz: Current events. The original idea was to talk about human sacrifice in relation to war-what's acceptable and not acceptable. It took years to get this show organized (mostly due to funding problems). Fortunately, by the time the show was finally possible and the budget appeared, it seemed even more appropriate in spite of one of the wars being "technically" over. Newtown had just happened, and the VA announced that the military was facing its most significant public health crisis ever, given the soaring suicide rate among veterans. For the first time we are losing more combat vets to suicide than we are to the enemy. Just presenting the numbers related to suicide gave us an avenue to talk about the war, to talk about military service, and in some ways to talk about the political economy of war. So all the elements just fell into place. We took the edge off with the block party, though.  CAE block party sign TA: Which is hopefully going to be a lot of fun... When dealing with hard data, there are many different strategies that one might employ in order to display that information, or make that information public. The way the data is presented here is sort of cold, liminal, but also comical in its juxtapositions. I'm wondering what motivated your aesthetic choices. Lucia Sommer: We were inspired by the Guerrilla Girls' early, very minimalist use of statistics to talk about gender inequity in the art world. Part of what we're trying to do with this show is encourage people to think about the way statistics are presented, particularly statistics involving human sacrifice and death. Statistics always, in a sense, demand narratives by the way they are selected and by the context in which they are presented. The minimalist presentation hopefully allows people maximal space to insert their own narratives and begin to ask questions.  Acceptable Losses at PNCA SK: The other thing, in this case, is that showing in a white cube or a gray cube somewhat determines the aesthetic for you. What goes in that space and what blends with that space? It's modern minimalism-it's what it's always been, and it's what you always get. It's clean and cold like the space itself. So both the context and the content of the presentation took us to minimalism. TA: I like what you were saying about letting viewers build their own narratives around this information. Putting the data out there lends itself to filling in the holes and gaps, in a way. I'm curious whether you're worried about whether the narratives that come out of those statistics might not be the narratives that you had considered or hoped to champion? There's a chance that someone might see the work and not leave concerned about authoritarian governments, let's say. They might instead just be interested in the fact that so many people are not dying right now from lawn darts. [SK laughs] SK: Lawn dart deaths... TA: When you leave a narrative so open, there's a chance that the narrative could move in directions that you hadn't considered. With your own particular subjectivity in mind, it's hard to gauge what others might see. SK: That's very true, and that's the chance you take. In this case, the deck is kind of stacked. We're in an art school; it's in an art school gallery. I think we've got a pretty decent idea of how people are going to make links. I don't think too many of them are going to find themselves in a narrative that's actually contrary to ours. This social sphere fosters a disposition that connects to the critical trajectories that are interesting to us. It's not like we are trying to do this at the CPAC [Conservative Political Action Conference] or some place where people are coming from a completely different perspective involving narrative possibilities that we would likely find incomprehensible or dangerous. However, even in that circumstance, I wouldn't be troubled by it. Say it's only ten percent that see the numbers outside of their normative interpretive grid, we're ahead! LS: When we say we're constructing a narrative, which of course we are-anytime you present a fact, you're already constructing a narrative—we try to keep the narrative that we're presenting porous and open. It's not totalizing like on Fox News or a didactic exercise. There is no "This is the data and this is the only way you can read this data." It's more of a conversation starter. We present these different statistics next to one another, for example, lawn darts: 1 death, which leads to them being banned in the US and Canada; and motor vehicles: 30 thousand deaths, which is basically accepted. We all more or less accept that allowing people to drive cars means there will be car accidents. And yet, on an existential level, when we get into our cars, we do not think, "I could die today in this machine" (although cyclists might have being killed by a car on their minds). The car remains normalized and practical, while the lawn dart is transformed into an abject object, one that is existentially associated with death. This is why they are banned, even though only one death was associated with them. It's that contrast that we're after. How you read that contrast, or how you start to think about it, or question it, is pretty open. Luckily, the ideology of death is not that well developed; how death is viewed is really ruled more by affect than by politics. TA: What brings you to the types of social ills you focus on in your work? It seems to me that they are impressively encompassing and applicable to a lot of different people - especially in North American and European contexts. Is that something that you specifically hope to accomplish? What might it look like if you were to focus on more local or specific concerns in the spaces where you perform your work or present your projects? SK: Sometimes we do; it all depends. Here we're doing something kind of generic, a gallery show, so you're going to get a more or less generic project. When we're brought somewhere for an interventionist workshop, where we have the knowledge resources of a local group that is invested in a particular area, we can do a project that addresses local concerns and that could only exist in that particular place. Again, these things are context driven. We don't come in with a set method, we have to look at who are we talking to, and where are we talking to them. Once we figure out the sociology of the situation, then we can decide what kind of project we can make. TA: [In that vein] Flesh Machine had been exhibited in many different locations and contexts. Did people have different responses in different spaces? SK: [laughs] It was remarkably reliable in the manner that people reacted to it. It produced this realization of how eugenics is still a part of Western culture. It was never really purged; it was simply latent. It went underground, and now it's emerging again. You couldn't go through the performative process and not get that. The kind of conversations, concerns, and anxieties that it produced were very much the same wherever we did it. TA: It would be nice to talk a little bit about what it is like for you all to work as a group. Working collectively can be a really powerful strategy, but at the same time, it can be difficult to sustain... SK: Yeah, other people. [all laugh] SK: In a word, there are other people involved in the process. TA: Right, and they have their own schedules or commitments, or maybe other points of view, or other strategies that they're interested in exploring. I'm curious how you resolve some of those tensions. LS: Well, we pretty much agree... [Steve and Tori laugh] LS: ...on the subject matter that we want to tackle. I think Steve could talk about that more as one of the founding members of Critical Art Ensemble. They specifically started working together because they all had a very strong anti-authoritarian... SK: Streak. [LS laughs] LS: Yeah. When you look at other groups — and we know a lot of people who work collectively — there are many different reasons why they fall apart. Sometimes it's the subject matter that they want to tackle, but CAE already has that figured out. However, the main thing that seems to get in the way are the nonrational elements of working with other people. SK: I think that's true, and I think that's what destroys collectives more than anything else. That's why so many groups can't function long term, they can only exist project by project. Many people have a hard time dealing with the affect that is produced when working side-by-side over time in such an intimate way. You have to love your fellow members, and you have to trust your fellow members. If you don't have those two things, it's just not going to continue for very long. That's what needs to be at the foundation of the group. LS: And you have to enjoy the process. SK: That's another thing, we've always been very big on pleasure. We'll do a more depressing and pessimistic show like the statistics show, but we'll then couple it with something like the Keep Hope Alive Block Party where we can be much more lighthearted. Even if it is kind of a gallows humor, we still get to have an approach that's a lot more playful, and that creates existential territories that mobilize so many varieties of encounters, conversations, and relationships that are counter to the limited sources of pleasure and sociability allowed by capitalism. Dancing in the streets has always been an emergent resistant form of behavior disturbing to authority. TA: Something that really struck me about the talk yesterday was the way you addressed "self-censorship." When discussing "Target Deception," you said that all of the self- induced micro-fascisms ended up being the greatest enemy of the project. I'm wondering what advice you might have for emerging artists who want to take risks or tackle certain political issues in which they might be confronted with self-censorship. When you are starting, you're just working things out. You're exploring. At that point, you might not have the same institutional support that CAE has to back you up. What are your thoughts? SK: Well, we didn't really start out with that institutional backing. That was something that came in the latter half of our experience. You could say that this is one of the really great things about working in a collective. You have each other to embolden one another. We can say to each other: "We shouldn't be frightened. We can do this together, and regardless of what happens, we're in it together." Just like being in affinity groups, that solidarity really helps a great deal in battling self-censorship-especially if you're doing provocations and interventions. It's better to be in a group than to try to do things on your own. As for the lone artists, I don't know what advice I have for them, because I've never really worked that way. CAE is the only way I've ever worked. LS: No one wants to censor themselves, but avoiding it is easier said than done. At least if you stay mindful of the problem, you can continually reflect on the process and ask, "Am I censoring myself out of fear, or because of a belief that something isn't possible?" SK: Also, always try to determine the difference between false barriers and an actual risk. For example, thinking "Oh, well, I can't work on a molecular level because I'm not a scientist" is a good example of a false barrier. Why? Because the equipment is available, and it's perfectly legal to have. It's fairly easy to use. Most of the processes are optimized. It's your own thinking that science is such a specialized domain that no one else can enter it that stops you from doing it. Those are the ones you've really got to watch out for. As opposed to, "If we go into this building and do 'x' we could be arrested." That's a real risk and you have to think about those in a much different way. When you're assessing a possibility or potential, it can be difficult to separate self-censorship from self-preservation. TA: Speaking of working in science and biotechnology, it seems like you all really embrace the prospect of working as amateur scientists... SK: As amateur everything. In some ways I think we're still amateur artists, because we just float around and do what interests us until it doesn't any more. TA: I think it's great. My feeling is that we should be treating our art practices as, well, a practice rather than... SK: A professionalized standard, yeah. TA: Definitely. Can you say more about the idea of the artist as amateur everything. Certainly, not everyone feels the same way... SK: I have no trouble with people who want to be specialists in order to turn out a certain product that has a certain quality to it. We need them, particularly in research-saturated endeavors. We support a plurality of methods, but specialization wouldn't work for me. I can't be an artist who finds a niche and produces different iterations of that same thing throughout their entire career. That would be really boring. One privilege artists have is that we're allowed to be kooky. We get a lot of license to behave in ways others can't. We're the only discipline that has speech authority for no reason. We're allowed to comment on anything. This is one of the few good holdovers from modernism. We get to keep the privilege, but can jettison the "genius" part (the original legitimizer of this privilege). TA: It's exciting. SK: Molecular biologists have to talk about molecular biology (and probably only some subcomponent at that). They can hardly talk about anything other than their small part of the universe with any authority. I just embrace this privilege that artists have been given. You can comment on anything and say "it's an artistic expression." To my mind, why wouldn't you do that? If you want to enrich consciousness and your life, you do that through the differentiation of experience. You do it by creating contrast, not by creating sameness. So take that amateur standard, and run with it wherever you want to go. LS: For me, also, it's what makes life interesting and fun, to always be learning something new. It gives you that license to embrace a subject or something that you want to explore and just learn. SK: I just want to emphasize that because we advocate this and think it's good for us does not mean that we are speaking against other methods for acting as a cultural producer. TA: I agree that its awesome to act as the playful amateur. However, some people take a lot of issue with that in terms of deviating from existing IRB (Institutional Review Board) sanctioned methods and strategies in fields like sociology, anthropology, and the hard sciences that were put in place to protect people [well, possibly in order to control information...]. Some people feel that going through human subjects boards, for example, is important in order to protect the individuals involved. Something you mentioned in the lecture yesterday that struck me was that most people don't care about transgenics, but when you put it into their world, they have to think about it, and they have to reckon with it. I think that's an interesting stance that resonates with me deeply. What about the people that don't get included in that framework? What about those that don't end up thinking about it deeply or creatively in the way that you had anticipated? In the case of "Target Deception" for example, in this theatre of the absurd, it seems like people could be harmed by interpreting that work in a different way. The gesture might just reproduce or reinforce the ills of the same regime that you intended to criticize. Target Deception, Germany 2007 LS: It could reinforce the spectacle of fear? TA: Right. LS: That's always the risk that you take. When you make a theatre that is presenting a certain face of authoritarian culture, in order to critique it, there is always the possibility that the critique won't come through, and the presentation of the authoritarian ideology or voice will dominate. SK: That's why you set the parameters in a manner that keeps people in a dialogic atmosphere so that you can undo that perception. I think that if the piece is working right, misperception is not a great danger- "Flesh Machine" was very reliable. The greater fear for me is that an authoritarian agency can take what we've done, recontextualize it on Fox News or some other media and say, "This is why we can't have amateurs. This is why no one should do science but scientists, otherwise you get these nuts running around spraying bacteria everywhere, and it could kill people." The recontextualization is not true, but they can say it in an authoritative tone and show pictures of us spraying bacteria. That's the scarier danger of what we do, but cooptation is always going to happen. That is what we must consider when assessing a project. How do you make it so that it is less interesting for the opposition to take, but still functions as critique? No formula exists, so you do the best you can. I would rather do an action that may fail, than embrace inaction, which always fails. TA: What other words of advice do you have for artists interested in working with your strategies? SK: My advice is to always make sure that when you engage a public you have a mechanism in the project that shows that public (whatever that public might be) what their stake is in what you're talking about. You have to qualitatively and personally connect them to the issue. If you fail to do that, they're not going to care, or it's just going to look like a bunch of didactic dribble. The other thing to remember when doing public projects is that operationally there is no such thing as free speech. You only have the rights that agents of authority allow you to have. Any action in public is illegal if police or other enforcement agents say it is. They have numerous laws to book people for completely arbitrary reasons such as disorderly conduct, loitering, blocking public pathways, public nuisance, public mischief, as well as very serious ones such as inciting a riot, vandalism, or causing a false public emergency. The Bill of Rights is not a guarantor of free speech. The closest thing to that is your lawyer. Free speech only exists in struggle. TA: Thanks. Acceptable Losses is on view at PNCA's Feldman Gallery through June 2, 2013 Posted by Tori Abernathy on May 22, 2013 at 23:16 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |