|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

What Can Sigmar Polke Teach Us?

by Victor Maldonado Today, February 3rd, 2013 is your last opportunity to view eight wall works and one suspended work by legendary German Pop artist Sigmar Polke at the Portland Art Museum. The suspended work, Untitled (1989), is a mixed media on synthetic fabric double-sided masterpiece, singular in nature and unlike any of the output from America's Pop-fathers, Rauschenberg and Johns, of whom Polke was an early adopter. Perhaps Warhol's serial approach to screen printed pictures also echos in this exhibit but it is the hand-made nature of these nine pieces that imbues them with a sense of lasting power. Considering the entire group, what at first appears to be an arbitrary array of works, upon deeper study becomes a compelling pocket survey of Polke's prolific career as collected by the discerning eye of Nicolas Berggruen Charitable Trust. The works reveal Polke as Germany's founding father of German Capitalist Realism (a politically charged manifestation of Pop Art), which like Warhol, mixes the sacred and profane, the everyday with the exalted.

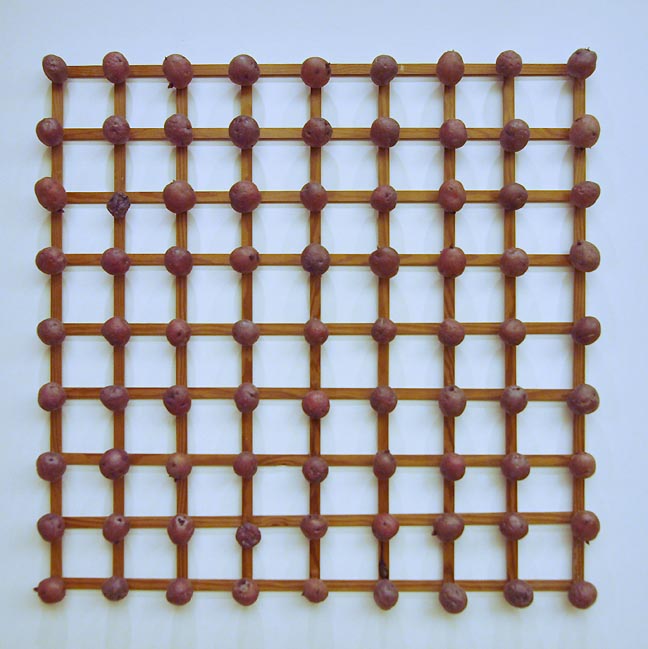

This exhibition attempts and succeeds at giving us a peek into the breadth of Polke's confounding anti-style approach to the craft of picture making. For example, Untitled (1963-65), comprised of a wooden lattice acting as the substrate for 81 potatoes placed evenly about the surface plane of the painting in a variety of small, knobby forms. From a distance they appear like polka dots but up close, reveal permutations that could only be created by nature herself with rich earth tones and patinated surfaces. The work seems like an elegy to poverty of diet and experience. I even overhead one passerby asking her companion to the museum if she thought Polke, "made a polka dot painting because his name is in fact Polke?" So seems to be the life of mid-twentieth century tongue-in-cheek pictorial humor.

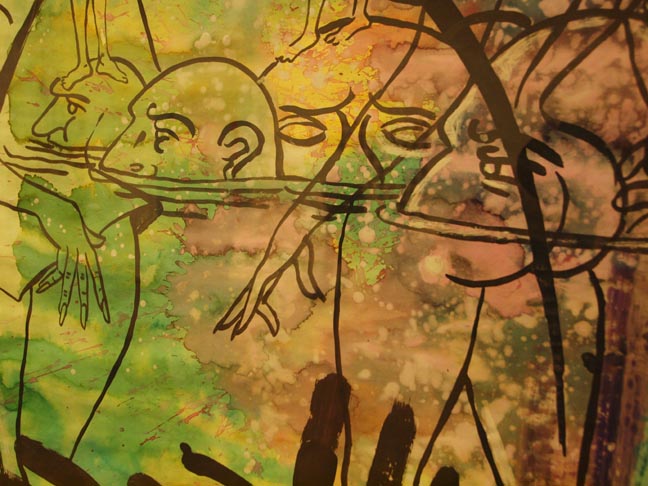

True, it's easy to leave it at the surface but Untitled (1963-65) leaves too many other questions unanswered when ascertained purely experientially. It's as if Polke challenges the passive observer to dig deep into the feast of meaning embodied both in the de-materialization of his substrate and the actuality of his subject. It is a showstopper within the exhibit, and many a visitor could not help do a double take at Polke's aesthetic paradox. Suspended from the ceiling amidst this one-man group show, Untitled (1989) is an orgy of figures built up as if enacting a human tangle. In this work Polke's informal, impossible bodies are translucent cartoons, reminiscent of primitive figurative paintings on Greek amphora. On its reverse, there is an even more rudimentary drawing in white paint conjuring a kind of hieroglyphic symbolism akin to Jackson Pollock's Guardians of the Secret (1943). Next, Streifenbuild 1 (1967) (Stripe Picture 1), deploys dispersion paint on canvas, creating an a-typical composition shedding any correlation to his earlier nearby potato piece by maintaining an abiding chameleon-like style in alternative materials. Here we witness the balance of gesture over decoration.

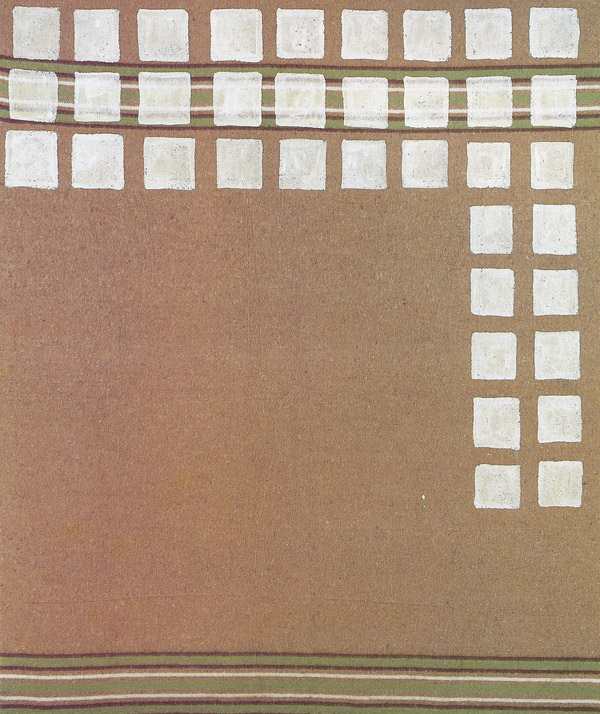

Next to Streifenbuild 1 (1967) is Wolldeckenbild mit kleinenweissen Quadraten (1968) making use of dispersion paint again but now soaking it into the pores of a cozy woolen blanket. The dispersion paint is applied in the form of semi-opaque squares of similar size, recalling his earlier potato grid, here though the surface is supplanted by brown, white and olive stripes. The picture feels like a worn façade of rudimentary architecture. Even when Polke doesn't deal with the body there are recurring calls to it. For example, he deploys and exploits the human figure with humor in Untitled (1989). It is a mixed media work that combines screen-printed, ready-made and found line drawing illustrations ranging from; partial figures, the birthing of Athena from Zeus's head, a flower (Fleur Crepon) and a rooster (Coq Tissu), a scene from a colonial battle, a white-bread family gathering around a modern dinner table, standing, climbing and hacking figures, a faceless nose protruding out from what at first appears abstract marks revealing repeating uses of the words revolution, among others, held up over price tags and 95F for "Rouleaux Papier Motifs Revolution." Moving beyond the banality of Andy Warhol's flatness, Polke conjures images built from now common methods of appropriation stacked coyly in a manner that he would become most popular for, as well as presaging a sense of virtual digitized space a decade before the internet made it ubiquitous. Where Untitled (1989) zings with common signifiers of middle class German culture, Providentia - Sleife (1986) (Providence Sharpens) zags with etherealness and otherworldly atmospherics. Here figure and ground merge in de-saturated earth tones and monumental semi-calligraphic flourishes creating esoteric, asemic writing. Here, gravity and chance seem to be in control, merging and submerging the granular minutia of mistakes and informal masses. Seeing nothing, the eye can begin anywhere, really. As Polke's contemporary Gerhard Richter so eloquently can be heard saying in the documentary film written and directed by Corinna Belz, "...a painting has to be good today, tomorrow, and always." Similarly, Polke's Proveidentia-Schleife still seems to have its way with us, like an ancient insect encased in resin suspended forever in time. Polke's tongue-and-cheek sensibility seems to enable a nimbleness usually missing from the experience of gazing onto the frozen faces of many paintings.

More sexually potent than Untitled (1989) and more explicit than the rest of the works in the show, and also the only work on paper is, Untitled (1983), juxtaposing washes of pigment with black line drawings of puckering buttocks and stylized breasts. Half submerged faces play stage to two bikini clad woman as if lifted from a New Yorker or Playboy cartoon that leave the punch-line out for our minds to fill in. Though Polke's air of mastery may not equate to that of his teacher Joseph Beuys and notable contemporaries like Richter in the mind of popular culture of cursory art history, he none the less is an adept painter of space itself with works such as the larger than life Lumpy Hinter dem Ofen (1983) (Lumpi Behind the Oven) and the paired-down and quite elegant Druckfehler (1986) (Printing Mistake). Both are similar to the space sandwiches of George Braque, another great stylist that is also relegated unfairly to second fiddle to the more popular Picasso. At PAM there is an opportunity to re-evaluate Braque's true influence upon Polke's oeuvre. With this exhibit we can sense the important lead Polke offered his developing contemporaries with his uncompromising tenacity to accept the new painting styles from New York while speaking with his own voice—truly a tough art to master for any artist of that time. Nowhere in these nine canvases is there a feeling of naive derivativeness. Always present is Polke's struggle to express something beyond the received and acceptable. His career is that of an artist whose sole responsibility was to, as Robert Rauschenberg posits, "...bear witness to his own time."

With these few works there is evidence of a painter witnessing the aftermath of war and a middle-class in quick transition to re-design itself and its values. There was a relentless desire for normalcy no matter the consequences, as well as a cognitive dissonance caused by such a violent break with tradition and the then near past. Polke is not a master of pictorial resolution, these are not static images. Instead, his canvases have a hold on loss and failure in a manner that is truly modern. It is a quality that any young artist should understand given the transient and decentralized nature of a contemporary global culture by the few, for the few. The beauty in his works is not classical in the sense of absolute truths and forms at rest, but rather of flexibility and resilience. Polke's lesson is that of a great stand-up-comic whose self-deprecation lends their audience the means to chuckle off the grind of the everyday, giving a reason to laugh off in belly rolls and guffaws the inevitable change and decay that we are sure to face no matter what false sense of security gets us through our own days. Posted by Victor Maldonado on February 03, 2013 at 12:08 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |