|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

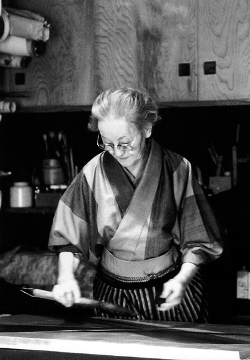

Toko Shinoda: Grande Dame of the Understated

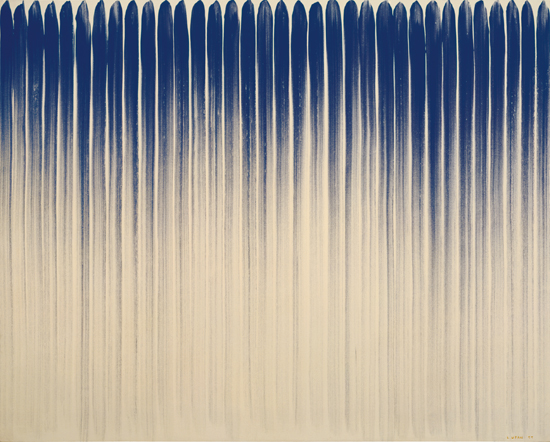

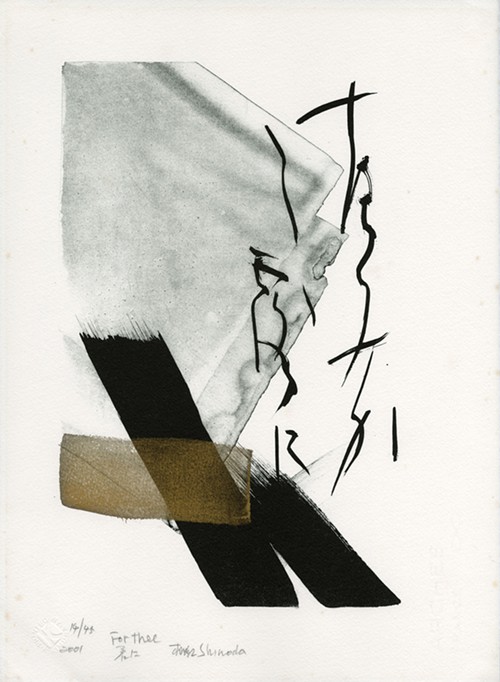

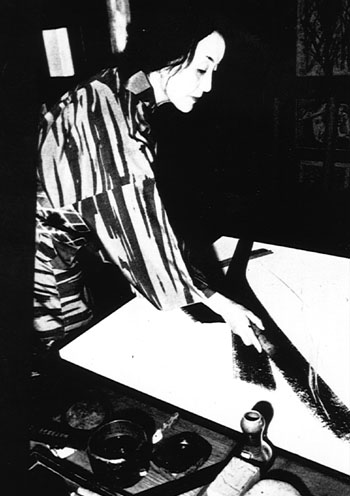

The white space in Toko Shinoda's prints and paintings is a mark whose character is defined by the other marks in the composition. Her elegant marks stretch and pop with the power of the elegant nothing surrounding them. Their very existence is defined by the nothing; they become significant characters, personalities even, as they sit, confronted and foiled by the expanse of white. In essence, each mark is made portrait by this empty space, situating each form's function, and relaying the nature of their meaning. Norman: I went to Japan in 1955 on a Fulbright. After the Fulbright, I went back as a diplomat, and when I was a diplomat, I decided I didn't want to be a diplomat anymore. On my Fulbright year and during my diplomat career, I realized how much I liked Japan. I have been in Japan most of my life now; I went when I was 18, and I am 77 now. I have been there as military, student, diplomat, businessman, and art dealer, all the levels of life I've experienced. I can speak Chinese and Japanese, and I suppose it's the language, but I have been there for such a long time that I consider the people of these countries as my people. I know everybody who everybody wishes they knew. I know the empress, movie stars, t.v. personalities, baseball players, and kabuki actors. And these are the people who I invite to my house and who I do things with. It makes it quite fun. People love to come to my house, because they never know who'll be there. A: Were you on your Fulbright to study art? Norman: I am the only person who studied Chinese linguistics in Japanese. I studied Chinese linguistics at Yale. Then I got the Fulbright. And my mentor asked me, "Why don't you study Chinese linguistics in Japan and see what their view is? You already know this material in English; why don't you get the Japanese perspective on late Tibetan and early Chinese?" Talk about esoteric. A: Wow. Norman: I had two children by this time. And, in 1964, I was one of the highest paid students in the world. I had eleven scholarships and fellowships that didn't overlap. My advisor at Yale was a genius. He told me to apply for this and this and this, and I got everything, because I was a hardworking student. A: So how did your path lead to art from linguistics? Norman: I quickly realized that there weren't going to be that many people interested in the relationship of late Tibetan and early Chinese. So, I thought it would be interesting to do something that could use my Chinese and my Japanese, so I became a diplomat, and I went to Hong Kong. While there, I began to collect, and as I collected, I realized that the Japanese prints and the collecting meant more to me than what I had to do for work. So I thought, why not do that? And my wife was extremely supportive. She said to me, "You decided what you want to do, and I'll help." A: How did you become acquainted with Toko Shinoda? Did you know of her work before you met her? Norman: It's a very interesting story. I left foreign service, and some very dear friend gave me the use of an apartment until we sorted our life out and found what we were going to do. It was a very elegant building in a lovely part of Tokyo. We lived there for a few months, and in the hallway, we would see from time to time, a smaller, older lady. She always kept to herself, and sometimes didn't even give us a greeting. But when I was in foreign service, we had started to collect, and I was a famous collector. A: Did she butt up against any difficulties being a woman working in Japan? Was it difficult to establish her career as an artist? Norman: She was lucky. She went to the United States in 1956 and was introduced to someone named Okada Kenzo, who was a very famous painter, who became her mentor. He introduced her to Betty Parsons, and Betty Parsons was the fountainhead of Abstract Expressionism. Betty gave her a show, and her work began to take off. In 1954, there was a show, "Japanese Art Since the War" , and she was in that at the Museum of Modern Art. When she met David Rockefeller, she liked him on sight, because his first words to her were: "I have ten of your paintings already." Norman: Well she has a great sense of humor. On March twenty-first, the Japan Society in New York will celebrate her birthday in a party given by Wilbur Ross, who is the chairman of the Japan society and is in charge of the birthday party. At my suggestion, they have gathered works from famous collectors in New York to be exhibited at the same time. Mr. Rockefeller has some of the burden of the gathering and the staging of the show. So I said to her: "You're lucky. You're a hundred years old, and you've got two billionaires fighting over you." She never married because she didn't want to report, she said. Ten minutes late at the grocery store: where were you? Not telling. She's still very active. She's still making work. Norman: Yes, in 1979, she won the Japanese Essayist Club Prize. She is also known for her writing. She is really sharp about everything. She is ancient, but she is still really plugged in about everything. A: Where does the writing and the visual work meet? Norman: I think people were after her because she didn't think like other people. Her essay is called, "sumi-iro", the colors of sumi. It hasn't been translated into English, which is a shame. A : Are the areas with calligraphy legible? Norman: Sometimes they are, and sometimes they're not, and she doesn't care. Sometimes the things she says come out sounding quite rude, and sometimes she means them to be. She has said, "I'm not writing literature, I'm writing art. I use it for the form. These characters were based on pictographs, and I am just doing my version of them. I don't care what the word means, I just want to fill the space with visual relief with the hard strokes of the characters." Sometimes she writes calligraphy to be read. In this show, there is one poem that Japanese readers will be able to read, but for the most part, the calligraphy is intended to be visual. Norman: Good question. People used to say that Elizabeth Taylor was a great actress who always claimed to not know anything about actors. And then people said she knew so much she could edit Variety. One time I brought said artist to her house, as she wanted to meet Toko Shinoda. Toko lives in a duplex, and asked her maid to bring me up and speak with her before they were introduced. She said to me, "Let's have some tea first and talk about it." It became half an hour that we were talking, and Toko said, "Oh, let her wait!" It was only an hour and a half time slot that we had alotted for their meeting, and with fifteen minutes, left, Toko brought up the visitor and said, "So you want to be an artist?" She later told me that this type of person only wanted to get a look at her, and that she had nothing to say to her. A: Oh my gosh. Norman: The grand dame. Another artist she heard about, she asked me to bring to tea because she thought she sounded interesting. So she was not a total snob, but a little one. A: Norman, do you see any real differences in the way the Japanese art market functions as opposed to the American art market? Norman: Well, yeah, but I don’t know anybody who makes work like her work. When she came to the United States in the fifties and met Betty Parsons, she also met all of the greats of Abstract Expressionism. Franz Kline, Motherwell, De Kooning, and Jackson Pollock and all of those people. She kicked around with them. She was 43 then, but she must have been known as what's common in popular parlance: as this hot Japanese chick. She was very pretty and very feminine, forty-three looking twenty something. She must have had them all eating out of her hand. It must have been very difficult, because she was so pretty. A: Did she simply come to the U.s. to look at work? Norman: Yes, she came to see what was happening here. If you look at history, you will see that 1956 was very early for Japanese to leave the country and travel. The government put strong controls on money, and you couldn't take money out, so you couldn't go anywhere. A: So how did she do it? Norman: She found someone who offered to pay her ticket. And she lived, for the first couple years of her career, as a poor artist. Betty Parsons gave her a show, and she was off. She went back and forth for about ten years. And she became quite famous in Japan, and now she's one of the most famous Japanese women artists. Everything that she makes sells, and she makes a lot of work. A: Do you see her work as being at all political? Norman: During the Tokogawa period in Japan, if you had political comment in your art, they cut your hands off. Thus, it is very hard to find political or social comment in Japanese art. She's very interesting, because people ask her what things are supposed to mean, and she can reply with devastating condescension: "My work is totally abstract, but please feel free to see anything you wish." You wish you'd never asked. I never see anything political in Japanese art. Beauty. We are after beauty. The word for art in Japanese is beauty. In Japan, the "sumi-iro" essay is her political views in writing. A: I wish I could read it. Norman: Everybody says the same thing. For Toko Shinoda's hundredth birthday, I have curated fifteen different shows around the world. This one here in Portland, in honor of the Garden's fiftieth anniversary year and Toko Shinoda's hundredth birthday, consists of forty-three prints and seven paintings. The one in Tokyo at the Kikuchi Museum, which will be the major one, consists of 33 paintings and seven prints. Norman: No, she only does solo shows. When asked, "Do you take any students?" She replies: "Picasso didn't." She has been written about as having accomplishments similar to Picasso, and it was something that was never lost on her. A: Do you think part of your attraction to her work comes from your linguistic background and her use of calligraphy? Norman: Visual and linguistic are not the same thing. When you say, this painting speaks to me, you don't really mean in language. Does the painting speak to me? Yeah, but it didn't say anything, I just thought it looked good. The balance of her work is so perfect that I could never find anything that I would want changed. Each piece takes your breath away. A: They are incredibly elegant. The negative space is so well preserved. Norman: "Yohaku" literally translates to abundance of white. I asked her once, does the white space have to be white? She said, no, it means: where there's nothing. So that is why she occasionally changes the color of the paper, to accent the form of the nothingness, which can be any color. She works every day on paintings still. She likes to work, and she enjoys it. And she's good at it, and it's fun. She's lucky because she's been successful for a very long time, and she doesn't need anything. She loved her time in the United States, and she remembers very clearly things that happened fifty years ago as if they were yesterday. A: Was she ever influenced by an event that changed her work significantly? Norman: People ask this all the time. She says, "I did it all by myself." She didn't find anyone to imitate or copy. When you learn to write the written language, you usually find a famous calligrapher to copy. But she didn't want to do it that way. She wanted to do it how she wanted to do it. A: She sounds like such a rebel. Norman: Since she was little! She never married. She was never attached to any school or movement. All by herself. A: That is amazing. Norman: Especially in Japan, where women did what somebody told them to, but not Toko-san. She enjoyed her fame, I think. Some people don't, but she knew who she was. I can remember many times going to embassy parties, and because of her I have a Bentley convertible and a Rolls Royce. One time, we went to the fourth of July party. There were probably 500 people in attendance. The cars come to the portico, and my car is rather special; it's an old Rolls Royce from 1976. And everyone said, "Who's car is that?", and she waved her hand and replied, "It's ours." Kind of a get out of the way kind of thing. A: Did she ever teach? Norman: She did during the war. She taught calligraphy to little kids, but her heart wasn't in it. She did it just to eat. When she became a famous artist, many asked her if she was going to teach, but she never wanted to do that. She wanted to make her own work. It's pretty nice to be around an artist who never did what she didn't want to do. But I don't know if she admits to that. I tease her a lot. She's fun, by now, she's fun. Before, she could be quite ferocious, because she was the grand lady. I don't know anyone who has led a life like she has in Japan. Deprivation came to everyone during the war, because it came to everybody. But she came from a good family. Norman: Well, they were gone before I met her, so I never knew them personally. Her father had a tobacco factory in China, and she had tons of kimono. In the war when things were bad, she would trade her kimono for eggs and things like that, like everybody did. She made a lot of money from big projects, and she has a fabulous place to live. I don't think she has had to worry about money for a long time now. She was always very generous and very tough on business. Once that was done though, she would shower you with whatever. She is kind of private, but I am in the inner circle, so I know lots of things about her. Still, there is no one to compare her to, because she just isn't like other people. A: Have there been many books written about her? Norman: Not so many. I have written one about her, but it's out of print. I only printed 10,000 copies, and I didn't reproduce it. I have written many articles and things about her, because she is the most interesting person ever. I worry about speaking about her life too much, because the focus should be on her art. Yet when you ask her about her art, she says, "I don't talk about my art. It speaks for itself." It is interesting to watch her when we go places. For example, she is a member of the Tokyo American club. From time to time, she invites me for lunch or dinner or whatever, and we go. And when she invites me, it's usually for some occasion, so she invites my employees as well, and I have five young Japanese guys that work for me. So she sits there, surrounded by all of these handsome guys, and people stop and say, "Oh, you must be Toko Shinoda!" And she responds with, "Yes, I am, and these are the people that sell my work." She realizes that if she makes a public appearance, the next week, my gallery will be filled with people that want to buy a piece just because they saw her. She never expected to be 100. And in the beginning, she told me, "I don't want to be a big seller, I want to be a long seller." And here we are, still selling, and she is 100.

Posted by Amy Bernstein on February 22, 2013 at 20:59 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |