|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Interview with Bruce Conkle

Although today Portland is full of conceptual and new media artists, when I first moved here there was really only one active practitioner on display, Bruce Conkle. His phantasmagorical time and sense scapes have evolved over the years making him the dean of eco art in Oregon. All the while his work has celebrated the odd boundaries between the natural and unnatural, ideal and real in his work and life (he does have a mock wood grain tattoo after all). Conkle's work isn't shrill or a scold so much as a court jester putting on a subtle Blackfriars style roast regarding the state of the planet and humanity's role in its current situation. Thankfully nature isn't always portrayed as friendly. As an artist he has exhibited at Brazil's A Gentil Carioca, New York's Jack the Pelican, Living Art Museum in Iceland as well as the Gobi Desert with Eco-baroque, his collaboration with Marne Lucas. He's also the lone conceptual/new media artist (ie craft or handling of media is downplayed to play up conceptual content) to receive the Hallie Ford Fellowship (in 2010). The first crop of 9 Ford Fellows will have an inaugural exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Craft in January 2013.

Conkle's current exhibition Tree Clouds at PSU's Autzen Gallery is perhaps his sparsest and most meditative effort to date. It ends today and will feature an incense burn from 4-5PM during the last hour of the show. Jeff: Let's start with basic history, you're a rare artist who is actually from Oregon (most are transplants), also where did you go to school? Bruce: Yes, and for college I initially went to the University of Oregon and got my bachelors degree, then I went to the Museum School in Boston for a couple of years. After that I ended up getting my MFA at Rutgers. J: What was the beginning for you as an artist? Was it High School? B: No I started as a little kid. I was always making things and playing with blocks and other things that were modular and could connect. I grew up in an place that had a wild area beneath it with a creek running through so I was always down there with a shovel digging holes, building dams and catching animals. I didn't have so many toys but I was always making things.

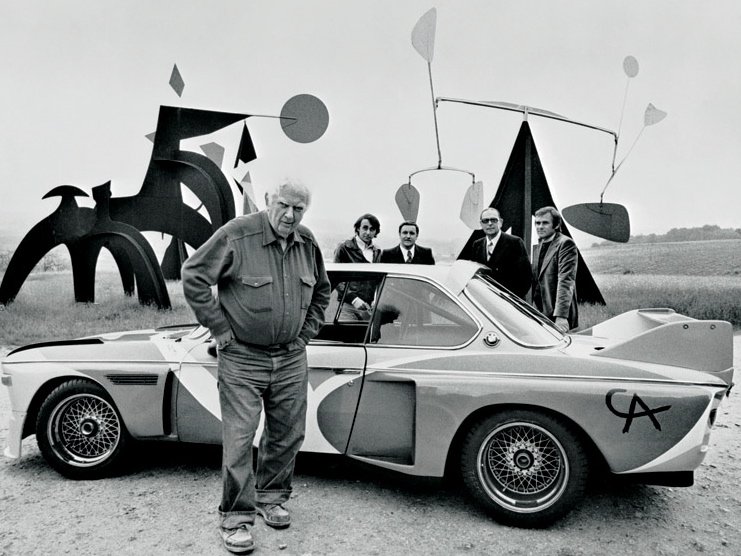

J: I came across your work soon after I moved here and it stood out because almost everything was wall based or "Commercial" but yours was perhaps the only new media work I came across. Was there much new media work around you growing up here? B: No, not at all. Matter of fact when I was really young my school took a field trip to the Portland Art Museum and there was an Alexander Calder show and they had one of the race cars that he painted. I believe it was BMW that did the series and I saw that and thought, "Holy shit! That can be art?" and it put contemporary art into my head, instead of just marble statues and canvas. You know the traditional things that you are raised with as the pinnacles of art.

J: and then when you went to the U of O did you study sculpture or painting? B: I actually studied film and video there, with a lot of Marxist theory and some production. There weren't that many art classes that I took then because they were impossible to get into if you weren't an art major and I wasn't at that time. I took one art class and it was really old school. We were making spheres, cylinders and cones out of clay. We worked on them for weeks and weeks and it was extremely boring. It wasn't designed to whet your appetite for more art. It was wedge driven in to separate people from art. J: (laughs) I just picture the final product of the class with everyone's spheres cones and cylinders all lined up... B: Yeah, and the teacher would even take a light and look at it from different angles and you'd work on it for weeks even. So boring and tedious. J: And you were doing installation art by Rutgers? B: Yes, I was doing installation work by then but it was pretty much on my own. There wasn't any school program, instead I kind of started doing it in my living environment and it transformed into gallery spaces. J: Ive seen some of the houses you've lived in... they are a lot like gallery spaces should be. The best one being the time you had goats in the back yard. B: They live on in the art still. J: and what other artists were you looking at besides your home space? B: The thing is Ive always found my inspiration not from looking at other artists but from just being out in the world. Usually the natural world but sometimes the constructed world as well. Although when I was younger I was really captivated by Bruce Nauman and Joesph Beuys. They were the two I sought out and I got to see a lot of their work as I traveled. It was actually a coincidence of seeing several exhibitions by those two artists at the time I was getting interested in them simultaneously. Thus the more interested I got into art the more I saw and the more I saw the more interested I got. And the Kienholtz's too. I think it was in Amsterdam I saw The Beanery for the first time when I was about 20 years old or so and it had quite an impact on me at the time. It wasn't that I loved it right away. Instead, it made an impact and it took me quite a while to process it.

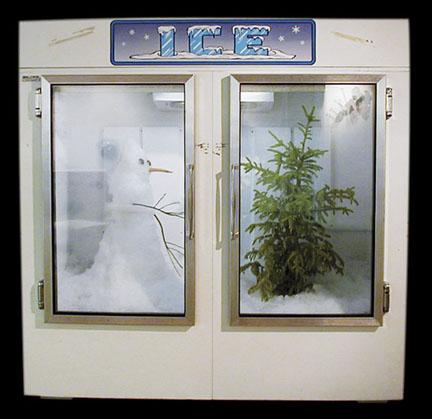

J: I remember that early piece that eventually became that Plazm cover. It was very cartoony and pop almost Flintstonesy or Hanna-Barbaraesque but things had changed by the first show of yours that I saw Cabin Fever at the Art Gym. It had a completely different, woodsier or folklore kind of feel to it. B: Grittier too. J: What catalyzed that maturing shift in your work? B: The sculptural piece your talking about didn't come from installation. It was more of a stand alone sculptural piece. It had an idea behind it about imperialism, colonialism and pop culture. It reflected the idea that the USA was dominating the entire world with its popular culture. J: And it just played whatever was out on the airwaves? B: Right, most of those pieces just played whatever was out on the air. And that was coming from a film and video background... studying television and media with a lot of Marxist theory and I realized that if I wanted to make a poignant critique in film or video I could spend countless hours and it would not be as poignant as whatever was on TV 24 hours a day. The soap operas and sitcoms were much more relevant. J: Then there were other pieces, just a few feet away from here in 2002 we did the Play show which featured your first snowman made from real snow (as art). It was a show that foregrounded new media as art... there weren't any traditional oil paintings or sculpture. B: There were snowmen before like in Cabin Fever. They were made of charred bark but yes that was the first one actually made from snow. It was in a freezer. The idea was that it was an artificial life support system for the snowman. It could survive but only by having a completely artificial environment, one which would pollute the area outside as well. The snowman wasn't alone since it also had a small conifer to keep it company. The question was did the snowman want to live in that very small and not terribly diverse situation? In theory the snowman could have survived indefinitely as long as the freezer was plugged into the grid and had power... but in practice it slowly shrank and got gaunter and more emaciated looking.

J: It had these huge eyes and it reminded me of Kafka's A Hunger Artist where a performer fasts and eventually wastes away so much that people forget he's in there and a black panther is caged with him. The Play show was this moment, where conceptual and experiential work was foregrounded rather than traditionally crafted mediums of stone wood and oil paint... or even how the work was put together. I remember how as curator I had to find a new carrot every week and the farmers market outside had several venders that would save their weirdest carrots for your piece. The considered it an honor when their carrot got picked. Then came one of my favorite exhibitions of yours The La La Zone Expedition at the Haze Gallery in 2004. Many of the figurines in the battle diorama held dental instruments or matches... as if the this genocidal expedition would result in a war of dental hygiene (a proxy for the way history gets cleaned up by the victors) and the wholesale scorched earth way of changing an environment to get rid of the nomadic inhabitants that were there before.

B: That show had snowmen too but they were tiny figurines. That show had all of these shifting scales like the human sized weapons to tiny figurines. It also had all of these video game stills with the figures removed so the viewer could project themselves. The whole show was about this real war (Iraq) based on fantasies and it was the first time I used the language of the natural history museum.

B: Right, the issue was that they were building these dams to provide power for a huge new aluminum smelting operation, so I created weapons and artifacts discussed in Icelandic Sagas from the region that the the dam would be submerging. I made them out of aluminum foil since the real objects were being lost and replaced by aluminum.

J: Your current exhibition Tree Clouds seems more Asian influenced than any of your previous shows? C: Well, travel has always been an influence and most recently I was in, Mongolia, Japan and South Korea... which certainly had an influence with the incense and the feather that causes the bell with the bone clapper to ring at a somewhat regular interval. The effect is meditative and soothing like the temple ceremonies. J: You've used incense before though? C: Yes, the show at Rock's Box had a censer and so did Warlord Sun King but it was after spending some time in Africa that I started focusing on it more. I went to Ethiopia primarily to study their carved stone architecture, but the scents were just as present as any building. Sometimes when traveling you expect to come across places that really don't smell very good, it's not just unpleasant... it can be oppressive... open sewers or rotting things. Then you turn a corner and meet an unseen and calming force, a whiff of incense that creates an invisible relief both mentally and physically. I'd ask people what they were burning and usually they couldn't tell me because they didn't know- just something that they found or picked up at the market. And at the market where they have all these varieties of incense the sellers didn't know what they were either- just bags full of twigs and resins or leaves and bark etc. Natural unprocessed things. I particularly favored the scents of natural resins, but I was unable to determine their origins, which trees they came from or whatever. It was a bit frustrating. The best answer I got was "We burn whatever we can find that smells good". On my return I was still thinking about that and wondering how to obtain amazing smells like some of the unidentified incenses I experienced there. Eventually I got to wondering what the aromatic tree resins from the Pacific Northwest would smell like, and I set out to find the frankincense and myrrh of this region.

C: The Ditch Projects people are starting a residency and I did a mini one to test drive it. Part of what I did there was collect sap resin from various trees. Sitka Spruce and Shore Pine. Basically, the idea is that these trees are often hundreds of years old and the resin incense releases that time capsule into the present. In Asian temples there is this different, meditative awareness of time. The bell with the bone clapper being struck by the feather and the incense have a similar sense of ritual. The drawings are more of an alternate reality or parallel universe where people are not around. J: Right, I can see Portland in the drawing and Mount Hood but besides the buildings and one satellite there isn't any evidence of people. B: At first I thought of having some tree stumps in the images but I decided that all you would see is downtown Portland from a distance filled with lava and Skylab, which was a space station in the 1970's. J: Ancient satellite porn in a meditative environment. Sound and smell in particular are more closely linked to strong memories than the other senses. In the past you've spoken about geological time and shifts of scale but Ive also seen a lot of shovels in your shows at Worksound, Ditch Projects and now here.

Posted by Jeff Jahn on December 20, 2012 at 12:20 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |