|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Fighting Men at Lewis and Clark

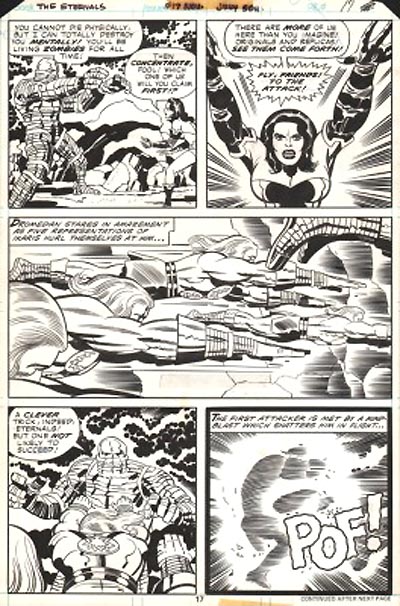

Fighting Men, (Foreground L to R) Peter Voulkos Untitled ice bucket 1998 and Leon Golub Interrogation I (2), 1980-81, Acrylic on linen, 120 x 176 inches, The Broad Art Foundation, Santa Monica, Art (c) Estate of Leon Golub/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY, (Background L to R) Voulkos, Kirby, Kirby and Kirby (photo Jeff Jahn) At first glance, Fighting Men at Lewis & Clark College's Hoffman Gallery appears to be an amalgamation of modernist ideals, the ruptured functionality of ceramics seen in the work of Peter Voulkos, the futurism of the early comic books of Jack Kirby, and the eerie, abstract depictions of war in the paintings Leon Golub. However, the three distinct bodies of work play off and compliment each other by building dialogues around dissent, power, violence, masculinity, and authority. An overarching power struggle between the work is what brings this exhibition to life. Moving away from their stout differences in aesthetic and media, the show conceptually weaves a cohesive narrative in history, as the artists are three first generation Americans, born in the span of seven years, all of whom experienced violence in the military. The differences of how each individual artist deals with this specter of violence is where the show gathers conceptual fuel; and what makes Fighting Men a great exhibition. For instance, Kirby's understanding of violence is part liberation, as seen in his comic Black Panther, where the marginalized are freed by a super hero and part of this articulation of violence revolves around dynamism in the sense that everything in the drawings is moving, rapidly changing, transforming. Kirby's understanding of violence is romanticized and optimistic through his depictions of future utopias and distopias; essentially violence is removed from its own physicality and is a mediated, fantastical experience.  Jack Kirby's The Eternals Looking at the next wall over, we see violence as a form of dehumanization and political oppression in Golub's Interrogation and The Mercenaries. Golub's work definitely begs us to ask how violence removes what we find inherently human and reveals a disturbing rawness to our human condition, as seen in the horrifically elegant, Napalm II. Voulkos, as the final provocateur uses violence in the process of the creation of his work, by twisting, pulling and ripping away at the wet clay. The movement of spinning clay definitely parallels to the dynamism of Kirby's comics as well which seems to never stop moving at speeds not of this universe. Voulkos is a strong glue that binds the show together by reminding us through his artistic process of the performative aspects of violence. This abstract physicality of violence is a very necessary part of the exhibition and exploring Voulkus' studio practice more in depth, as seen in the historical film on the three artists in the back, this performance also speaks to the spontaneity of the medium and those who influenced Voulkos, most notably Merce Cunningham and John Cage, fellow fighting men of the avant garde and professors at the experimental Black Mountain College where the three taught during the 1950s. This ruptured functionality is visually stimulating and at times, even folkloric. Examine Babe the Blue Ox aka Tall bottle, one of the only truly functional ceramic pieces in the show. Voulkos establishes that while the modern conventions around him, like the American folklore oral tradition or the craftsman tradition of ceramics are valuable, he can expand the media and reinvent ceramics with a more conceptual, than functional undertone.  Peter Voulkos Untitled plate (2000) courtesy Frank Lloyd Gallery This visual roller coaster of ceramics, painting, and this montage of comics is a visual experience that creates tension between the work but allows the viewer to see each piece stand alone. A struggle forms from this hegemony of the lowbrow comics versus the fine art of Voulkos and Golub; and this tension may seem problematic, but symbolically fits the theme of Fighting Men. Curator Daniel Duford has brilliantly articulated Kirby's frustration of being a comic book artist; someone with great talent but who struggled behind the scenes as an anonymous drawer and never had a gallery show. However, do not forget that Kirby is essentially the godfather of modern comics and inventor of the Marvel universe and created every character from the Avenger series. Through this show, Kirby's work is given some well-deserved credit through its comparative relationship with Voulkos and Golub, artists whom have definitely solidified their legacies as fine artists. The show's huge Golub paintings, definitely the most breath taking work in the show, critique the violence and atrocities of the Vietnam War and more subtly, critique the lack of context in abstract expressionism. As Duford writes in the show's catalog, "Abstraction was a willful disengagement from the world; the art that was understood as most important at the time was mythic, self-reflexive and free of narrative. Figurative art was seen as hopelessly provincial or a vestige of European decadence." So in a time when abstract expressionism was top dog in contemporary art, Golub took its materials and morphed its unworldliness into very real and evocative scenes. His process was even violent, he used meat cleavers to scrap the paint into the canvas. By using its texture, its rough brushstrokes, the torn, unfinished aesthetic of the canvas, Golub delivered a harsh critique of his contemporaries in the New York art scene like De Kooning and Pollock. The work is mesmerizing while haunting. Come for Golub's mural work, but definitely explore and dissect the politically charged sketches from post-September 11, very strong and impactful forms of ephemeral dissent. This is on the immediate left wall and includes a series of paintings called We Can Disappear You. The aesthetic experience of the show is slightly sporadic, as the featured work has a huge spectrum in size, with the minute detail of Kirby's comics to the colossal scale of Golub's paintings. But Duford has arranged the work to have quiet moments amongst the stronger, larger work. The three bodies of work stand strongly alone and the natural progression of the viewer's gaze from the comics to ceramics to paintings is fluid. Daniel Duford made an interesting curatorial choice by never isolating the work of the artists; all three appear together. This reaffirms the themes of show by allowing each artist to present what violence is to himself, and then deliver a critique of his own human condition. Posted by Drew Lenihan on December 17, 2012 at 1:57 | Comments (1) Comments Obviously this is a very loaded time with the recent horrific outbreaks of violence (Clackamas and Newtown) the issue has once again come to the fore. The one thing that I feel is important is that we not treat violence as some remote or fantastic reality or even a purely polemic one... but as something everyone takes personal responsibility for (including politicians as social policy instigators). It seems obvious that something must change... but will it? Luckily, that responsibility is something that Fighting Men does engage and the violence seems bound up in personal and moral consequence. This isn't violence for the sake of fetishing or producing the adrenaline that is a natural consequence of that action... it was a way for men of that era to codify their first hand experience with warfare, making it a mental health issue with sociological expectations. In many ways it is the existential parsing of warfare's polemics and longterm effects more than the violence itself that this art addresses. It would have been interesting perhaps to open this group show to the present by addressing video games: http://www.npr.org/2012/11/20/165578004/gamer-explains-appeal-of-first-person-shooter-games and movies as well... but perhaps that is another more ambitious show?

Posted by: Double J Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)