|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Changes | Happy Birthday: A Celebration of Chance and Listening at PNCA's Feldman Gallery

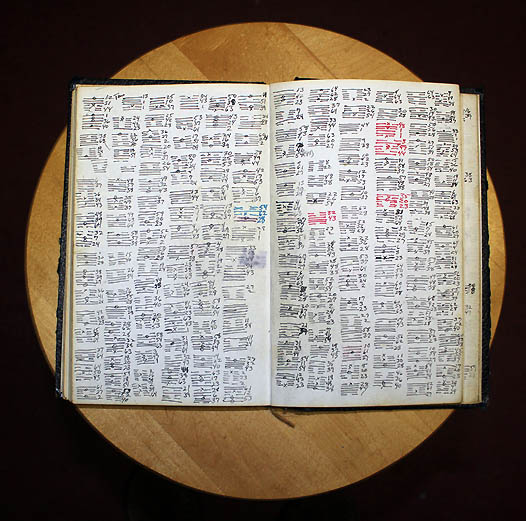

About twelve years ago, I quit throwing my three pennies. I cannot remember if it was a gradual shift nor recall specifically why, whether out of newfound self-confidence or perpetual disappointment. But I never tossed out the notebooks. Cage aficionados might find some interest in this end decision (or, as this essay progresses, take umbrage with my limited knowledge of Cage); Cage, a practitioner himself, might find the result sublime; and, as for myself, I now make photographs of the pages. I re-learned the coin arrangements of the I Ching just for this exhibition. In that it is a birthday celebration, I thought I'd bring an appropriate gift: #62, Preponderance of the Small* Chen: The Arousing, Thunder THE JUDGEMENT THE IMAGE THE CHANGING LINES 6 in the 2nd place: Changing lines make a shift in the reading that creates a new hexagram. In this case, it is #34, The Power of the Great Chen: The Arousing, Thunder THE JUDGEMENT Inner worth mounts with great force and comes to power. THE IMAGE In that there are sixty-four hexagrams in the I Ching, chance, albeit with a fixed probability (and rather high) brought us to the above two. The book's commentary gives some guidance, speaking of attention to proportion in pursuits from which then comes success, eventually followed by greatness, as long as it is just. The proportion, however small, is nonetheless intensely observed in order to be appropriate to the endeavor. What may be seen as non-striving is more of knowing one’s place, but not passively, as the action is the choice to stay within a familiar realm. Despite help from the authors of the book, confounded with further elaboration by this writer, any interpretation may little benefit the curator, Mack McFarland, or the still living artists in the exhibit, to say nothing of an audience for the show or readers of this essay. After all, how do we suss consensual concepts from the imagery when, for instance, "Heaven" may be your gods while the firmament for another? Precisely. Do with it what you will. Cage does.** Forget I said anything. I am released to address the art itself. Cage often used the I Ching in conjunction with a grid of sixty-four squares. The hexagrams that he rolled or threw were marked down on the corresponding squares to determine placement of a score or marks on paper; it was not a quest for wisdom or knowledge but rather quite the opposite: the release from "knowing", letting structure come about of it own.

Luke Murphy employs the I Ching in a similar manner as part of his multi-media piece, "Landscape with Changes." Hexagrams come and go in the lower left hand corner of the monitor as basic forms that represent clouds, escarpments and the horizon, all which shift in their placement according to an algorithm - as opposed to a rationale — based on each hexagram. The needle on the Geiger Counter that accompanies the video jumps as the device detects ambient radiation, but this does not seem to coordinate with the images on the monitor. One learns from Murphy's website that he has worked with radiation detection in determining "random" constructs for other, similar works, and perhaps I am missing something, but there seems to be a (mechanical) disconnect here. Nonetheless, I am left to the wonder if belief systems are like the air or geologic time, things we barely detect yet interpret to be part of a natural design.

Paul Kos' "Sound of Ice Melting" is similar to Simek's piece, if not in scale, in its elaborate setup to emphasize (capture) a natural process. The variables of physics involved in ice melting certainly may be calculated in scientific equations and then put to some practical use. Not so here, as the amplification of the microphoned space is such on my two visits that what issues from the speakers is the sound of people in the adjacent room, and at a level that is lower than the ambient volume in the room. There is a reel-to-reel tape deck sitting on a table with two mixers and an amplifier. The reel does not move. (No posterity.) Even so, I know the sounds of ice melting, the cracks and pops as cubes melt in a glass or as a northern lake thaws, which actually leaves me free to leave the chunk of ice to its own devices (chance) and look at this piece more as a somewhat monumental and elegant sculpture. Cage has said that chance operations ask questions, a preferable place from which to operate than finding answers - if not acknowledging results - for while such a hands-off intentionality is surely capable of brilliance amidst happenstance, some selection process must occur before and after, which further causes me to consider the distance of the artist from the work. In the strictest sense of what constitutes chance, the ice alone in Kos' piece comes close to fitting the criteria for chance operations, for after the block is placed, it is left alone and influenced only by external forces like a wind current created by a passer-by or the temperature of the building set by a custodian. Art that incorporates an element of chance might instead be judged by the contingencies introduced by the artist. After all, it is the artist's intent that allows such occurrences, and this in itself is unavoidably and necessarily symbolic.

Cage's "Not wanting to say anything about Marcel" is perhaps the most enigmatic work in this show. Eight plexiglass panels have been imprinted with words and word fragments. There is no syntax to be found, nor immediate associations to be made between the words. While this might be an issue of what transferred and what didn’t in the printing, and may be the "chance" in the process, it may also be that the process is thematically tied to the title. Cage talks about his relationship with Marcel Duchamp as if it was one of acolyte and master, although comprised more of admiration than interaction. Cage's impression was that casual conversation seemed to be out of the question and unworthy of Duchamp's time and energy. This, however, does not preclude a desire to engage, for eventually Cage asked if they could play chess together. Even then, one can imagine that a level of admiration persisted, and their interactions were cherished by Cage and even found inspiring. The question arises, then, of what to do with this inspiration? As romantic as it may seem, I would like to imagine that so precious their relationship, and wanting to somehow honor it, Cage dared to preserve snippets of their conversations. In that the words give no clue as to their meaning within the relationship, the sculpture becomes some kind of file holder for memory jogs that have meaning only for Cage.

All of the work in this exhibit has been executed with or is accompanied by art markers such as frames, pedestals, shelves, or arrangement, which does not speak to anything necessarily lacking in the work or curation as much as the limitations the art making and exhibition process necessarily imposes. It is with this in mind that I am drawn to Brad Brown's "Liberty of Animals," not because of their dull color pallet or the numbers, dates and what-have-you, and most certainly not because of their arrangement in a grid. Instead, I take note of the numerous nail holes in the corners of each, as if they have been arranged and rearranged time and again, whether at random or according to some method. Each time they are hung, an area of their surface disappears, and one can imagine a time when Brown's work will not hold a nail, and then what?

Walead Beshty's FedEx(R) Kraft Boxes fulfills the same function, if more explicit, for there is an attempt to keep the piece "whole" by shipping shards and all else of the glass box to their next destination. Some dusting of glass may be left behind, and there may come a time when Beshty's glass boxes are nothing but dust, thereby mimicking the processes of dissipation and entropy, yet there will remain a preciousness as art object because the documentation of it's dissolution is the art. Perhaps "improvisation", as opposed to chance, is a term better suited for much of the work in this exhibit, as the artists establish and interpret a given structure, the confines of which are the working situation that asserts a dominance over outcomes no matter how arbitrary the works may or may not appear. Still, we can allow that these practices are subject to a certain degree of risk. Indeed, it might be better to for the artist alone to consider the outcome to be art and then file it away, for should a selection process follow that does not consider input from the part of the process for which the artist does not assume responsibility, any amount of consensus nullifies a good portion of the spirit of the work. However, all is not lost, particularly from an academic need, as we may find ways to respond to the methodologies employed by the artists. I have this long-standing idea that the near-artistic ideal is simply to do nothing, to just let the walls talk to each other. (Understanding the infinite, we would have no need to speak.) "Nearly-ideal" because the very nature of an ideal is that it is unattainable, even if it is to think of doing nothing; so we settle for something that begins with second best, which is to do next to nothing as a context (otherwise known as initial intent). Duchamp and Cage, among other artists of the last century, showed us the baseline of art with the readymade and 4' 33" of silence. To replicate their processes are to re-contextualize the seminal, and by extension, we not only have this excellent representation at Feldman, but much of what constitutes art today. Whether these early endgame players realized it or not, they pursued these lines so no one else would have to ever again (including themselves), and in doing so, reminded us that art's true hallmark is the unending potential as some thing, no matter how small or elusive the gesture behind it.

* For my purposes, I have used the Richard Wilhelm translation of "The I Ching or Book of Changes," which was rendered into English by Cary F. Baynes. Princeton University Press (1950) ** References to Cage's thoughts and methodologies have been drawn from Richard Kostelanetz's book of culled interviews with Cage over a 40-year period, 'Conversing with Cage' (New York: Routledge, 2003) Posted by Patrick Collier on October 11, 2012 at 12:55 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |

Works by John Cage and Walead Beshty at PNCA's exhibition

Works by John Cage and Walead Beshty at PNCA's exhibition