|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

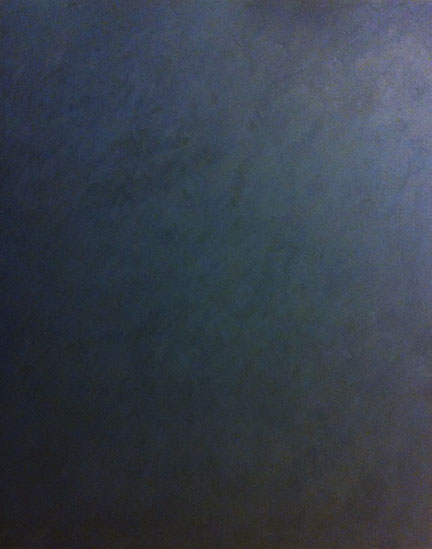

Gerhard Richter at PAM  Seven Works by Gerhard Richter at PAM, Grau (Grey) on the left (All works on Loan from the Nicholas Berggruen Charitable Trust) Currently on view at the Portland Art Museum are Seven Works by the German painter Gerhard Richter, on loan from the Nicholas Berggruen Charitable Trust. The works are often monochromes, the most spectacular of which is Grau (Gray).

Gerhard Richter, Grau (Gray) 1972-73, Oil on Canvas On Loan from the Nicholas Berggruen Charitable Trust Grau is not much to look at. It is a large painting that seems to be over 5 feet tall and perhaps 4 feet wide. The surface is a more or less even, marked only by the random strokes of a relatively wide 4-inch flat brush. There just is not much to see. But then again that is the point isn't it? I don't think Richter was out to find the limits of paintings, he was out to destroy it. Grau is a type of painting that gets made when painting is no longer possible. Everything that we know about paintings is ruthlessly stripped away: Color-gone, Composition-not necessary, Narrative-please, you can’t be serious, this is the 1970s after all. It is a painting without a past and more importantly without a future. Gray monochromes are not really an idea that you can build on.  Detail of Gerhard Richter's Grau (Gray) 1972-73, Oil on Canvas On Loan from the Nicholas Berggruen Charitable Trust One gets the feeling that it is a painting made out of frustration. Maybe he wanted to make a painting that would be completely objective. Gray, being neither black nor white, is neutral, rational. It is also the type of thing that gets made when the language and history of painting are no longer able to tell us anything new, and the same forms and ideas are endlessly recycled. So Richter makes a painting that destroys everything that we are taught is essential about painting. While the destruction of the ideas and the foundation of every medium is periodically necessary, there is no guarantee that an artist will find something useful in the ashes. Richter does. The first thing we learn is that painting is surprisingly resilient. It is fully capable of getting by on the barest essentials: a support, an intelligent color choice and a few brush strokes here and there. At the time, this must have seemed very close to not being painting at all. The last layer of Grau is painted with a brush, which is a dead giveaway that we are looking at art. Other paintings of this time were painted with rollers, which would have blurred the distinction between the application of paint on the painting and the wall behind it. Grau is a painting that is not much to look at but is wonderful to experience because it is a deep meditation on the possibilities of painting that was made by asking hard, fundamental questions about the nature of the medium. Fast forward and we are looking at this painting in Portland in 2012 and not Germany in the 1970s. What does a painting like this mean for us today? We look at painting today very differently than artists did back then. Even today, Richter paints with colors, compositions and yes, occasionally narratives. But does it give us a free pass to side step the issues posed by Grau? I don't think so. Richter asked deep questions about the medium, destroyed it and came up with new solutions. Would we see his abstract paintings if he hadn't made Grau first? Again, I don't think so. His abstract paintings seem like a lesson on how to take the raw ideas that he experienced in Grau and turn it into something more relevant and robust that actually could be developed over time. But in Portland today, I think that there is an important difference. He destroyed everything to make it new for him. He destroyed it because he had no other choice. I am not convinced that this is something you can learn by looking over Richter's shoulder. It has to be experienced first hand. It is something that we will have to discover for ourselves. If we choose not to, we will endlessly recycle tired forms and ideas that we do not really understand and never really belonged to us in the first place. We are in danger of becoming everything that Richter was reacting against. So maybe there was a lot to look at after all.  Portrait of Albert Einstein (1972) Oil on Masonite On Loan from the Nicholas Berggruen Charitable Trust Gerhard Richter Seven Works at the Portland Art Museum Through September 9th 2012 Posted by Arcy Douglass on August 17, 2012 at 10:40 | Comments (10) Comments Arcy: You write as though it was a found truth rather than a manufactured convention that painting had to be conceptually rebuilt in the 70's. Sad but true that some felt it had to be rejustified in order to conform to the extremely narrow range of discourse considered permissible by the gatekeepers and tastemakers in that wretched period but that's not the same thing. Painting has always been and will forever be an extremely adaptable medium, well-suited to register one's engagement with the world; if it seems at any time to be ill-suited to the passing Art World concerns of the day my concern would be for the viability of the insular Art World, not for the medium. Posted by: rosenak

I think that Richter's crisis was genuine. He loves the work of Caspar David Friedrich and at some point he must have asked himself why his work in his time would look so different. He looked at what he was doing making paintings from popular culture magazines and found it wanting. Richter was probably even surprised by his own lack of sincerity of in his own work, something Friedrich had in spades. If my history is correct, I think that when Richter was making these paintings he had already had a falling out with his dealer Heiner Friedrich and was teaching and painting for himself. Also, when you look at the paintings they do not seem like an intellectual experiment about the bounds of painting. This is a painter destroying everything he loved about painting. In a way he is trying to find rock bottom, a solid place to stand so that he can find something meaningful. I am not sure that I agree that the art world is interested in change. When things change people lose a lot of money. Posted by: Arcy Thanks for your reply. If Richter's crisis was personal my quarrel is not with him but with your statement "...the destruction of the ideas and the foundation of every medium is periodically necessary" (unless I'm being too literal). The foundations of painting have always been and will always be sound. No artist ever destroyed them, whatever was intended or claimed; all anyone can do is build on them and expand our vocabulary. Destroying the foundations of painting sounds like vainglorious folly to me, and it also sounds totalitarian if one means to destroy them for others as well as for one's self. Posted by: rosenak It is just the way painters speak of painting (especially in the 70's) so you might be taking the word much too literal. Destroying painting periodically is just part of the way painting lives. In architecture buildings literally get destroyed (the Vegas Strip is a prime example) and I know a couple of photographers that want to "destroy photography." Even the idea that "the market" is destroying art doesn't make any sense... it merely influences its growth. Posted by: Double J Yes, I know, I'm familiar with that sort of empty grandstanding -- John Lydon setting out to destroy music, for example. Well done, Johnny. ps -- Since my last post I've been hoping no one will challenge me to identify the foundations of painting because come to think of it I don't know or care. Thanks! Posted by: rosenak The point it is it isn't empty when it leads to an artist like Gerhard Richter! He's not a favorite of mine but I can't deny his relevance (though I'd like to). The closest Ive come to it is, "Richter is the German painter that US collectors find the least threatening." I should have gotten into a fun argument with Rob Storr over that statement but frankly I had better things to discuss rather than bait him, Since you claim you don't care, what is your story? Posted by: Double J If I understand your question, what I mean is that in my decades as a very active painter I have -- it now occurrs to me -- literally never asked myself what the foundations of painting are, and now that I do ask I find that I don't really know how to think about the question; it seems too abstract or maybe it's that there are too many ways to think about it to settle on what the question means. I say I don't care because either I don't need to know or else I've internalized the answer through my practice and my experience looking at art and in any case I feel I've been getting along just fine. Posted by: rosenak As for Richter's relevance -- relevant to whom or what? He interests me insofar as I respond to his work and not much beyond that. I have a very strong sense of what I'm doing in my own work and don't feel I have to know what everyone else is up to, however influential they may be. Posted by: rosenak For someone who is so "secure" and doesn't feel they have to know what others have done you have curiously responded a lot to a post on Gerhard Richter. You've done so because his work is relevant to you. Unless you have something to add to the discussion about Richter I will delete any further posts. Posted by: Double J *Deleted... PORT is not a venue for attention seeking behavior. Even if you are a good painter who does fine gray paintings... Posted by: rosenak Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)