|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Among Friends; Joe Macca's Two Man Show at Marylhurst's Art Gym

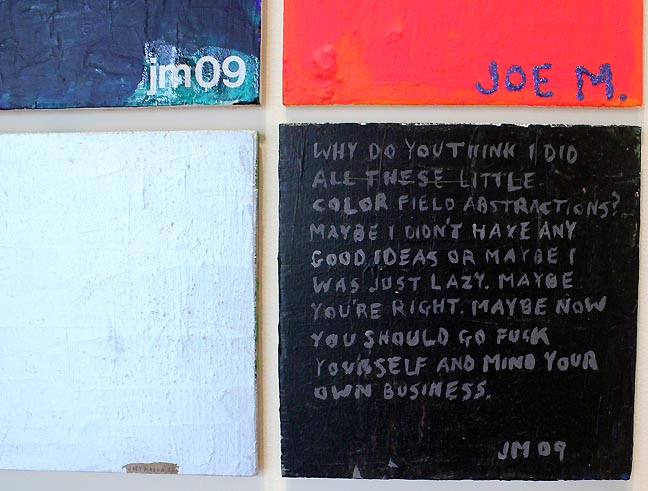

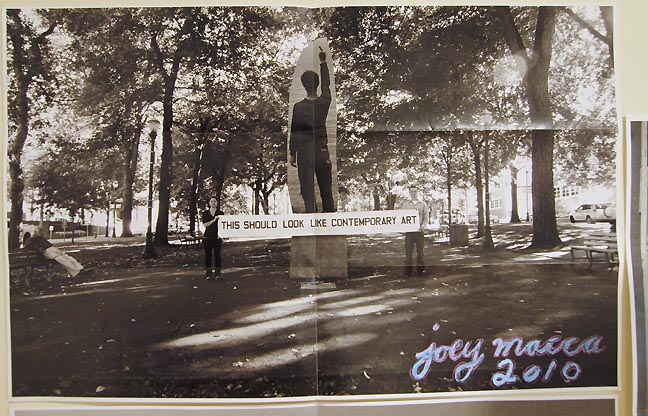

If one were to take the two Cs in Joe Macca's last name, rotate them clockwise 90 degrees and smoosh them together, his name might then read as "Joe Mama," calling to mind the type of joke that relies on tasteless creativity in pursuit of one-upmanship. Stupid, ugly, poor, fat, or any other derogatory term these slams are built around, in the wrong setting are fightin' words. But these jokes don't always lead to violence. In organized "Yo Mama" contests, opponents compete to see who can come up with the vilest yet creative analogy. An agreement among like-minded practitioners to participate implies camaraderie and the understanding that by engaging in the activity, one must endure the abuse along with the risk that an element of truth lays therein. And even though brashness counts, if the teller of the joke fails in delivery or creativity, that would-be comedian then becomes the object of ridicule.  Installation view (photo Jeff Jahn) I am, of course, not alluding to Macca's color field paintings that are included in the exhibit at the Art Gym, nor will I have much to say about those deft works in this essay; instead, for as if bee-line-drawn to the salacious, it is Macca's small paintings and paper constructions I wanted to see. Nor do I mean to imply via the opening paragraph that Macca falls short in his efforts to titillate and amuse. But is he too brazen?  Joe Macca's arm at his opening On the whole, it may be assumed that most artists have a basic insecurity, a void, a lack that must be fought: Is my work getting the type of exposure it should? Is my aim true and are my motives sacrosanct? Is the work up to snuff personally, historically and amongst peers? To some degree, these things are all part of the inner dialogue. And don't let the smooth, suave operators fool should one want to point to these people as a counterpoint. The difference, of course, is how much one indulges these doubts when setting out to make art or moving about in the social world.

Of course, for anyone to acknowledge or speak of such things is a bit untoward, for they play into the tired cliches that artists must suffer, taunts that disallow wallowing in romantic notions held close to the heart. Not unlike betraying the secrets of one's collective as a gender to a member of the opposite sex, Macca exposes the underbelly of the way artists feel about themselves and their profession. The secrets of the delicate sensibilities. An irony in this, if there is one to be found, is that this is no different in any other social clique and part of being human, even if artists breathe a more refined air and expect more latitude. And if this is true, then artists should be expected to give more leeway as well. For instance, the late night drunken emails to either imaginary critical foes or those who neither help nor truly understand one’s art are forgiven by the receivers as we take our Kumbaya spirit to a higher level and muster compassion and empathy for one of our own in such pain, for we too have been there and done that, or certainly wanted to. Macca makes this faux pas public and calls it art. Is he allowed such license? And just how serious is Macca? If we take Macca's gestures of self-aggrandizement with a grain of salt, then so too we must snicker when he calls out another artist. And, if still bothered that Macca makes fun of other artists or defaces their work and calls it his own, then it is you who is in need of another's compassion and understanding, because somewhere along the line your sense of humor settled in your spleen.

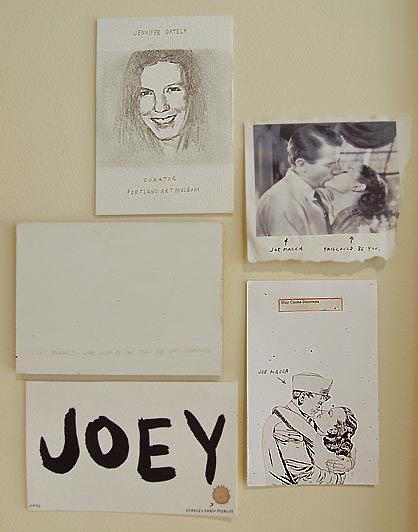

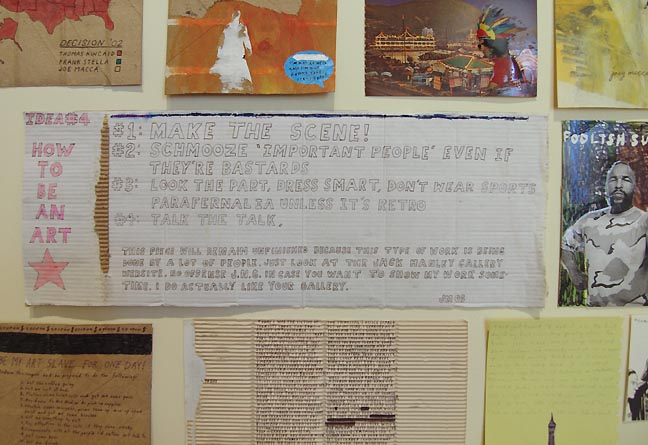

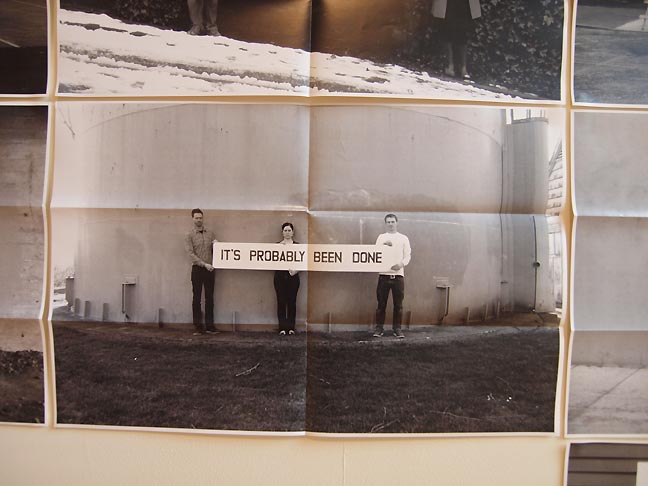

All of this insider fluff may mean little, if gleaned at all by those outside the clique, and it may even be confusing why two such disparate bodies of work by the same artist are shown together. Yet, there is a method in the curation, one that I would argue goes beyond the "Two Man Show." Entering the gallery, one first sees Macca's abstract work. There are two different bodies of work within this grouping, yet they are not dissimilar from each other and present a consistent whole. They are also what one might expect to find in a staid, serious exhibit. The small works that I have spent the bulk of my time extolling are in an adjacent room, for which exterior, demarcating walls were built for this exhibit. The creation of the two rooms provides us a literal placement reflected in the title of the show. Yet, there is third, smaller room that is also behind this partition, one that contains postcard and mail art by other artists, namely Mack McFarland and the duo Anna Gray and Ryan Wilson Paulson. Like some of Macca's postcards, many of these works have been sent to the curator, Terri Hopkins.  Mail art by Anna Gray and Ryan Wilson Paulson Initially, these additional works by other artists feel somewhat incongruous to the Macca exhibition, an extension yet an afterthought, rather like "Hey, I have an idea! You (Joe) sent me postcards, and so did other artists. Let's show them as well!" And it is here that the curatorial hand is so strongly felt (aside from putting the more conventional work in the front room) that one wonders just how many people should we consider are in this exhibit. Certainly more than a "Two Man Show," and perhaps as many as five. It is only after spending a considerable amount of time in these two back rooms that the reasoning behind including these other artists starts to make sense beyond the obvious.  Macca's mail art Granted, Macca has appropriated (defaced) several of Gray and Paulson's mailed pieces as his own art. This may be one opening to a segue. But by examining the motivations behind sending postcards, the curatorial decision might be more fully understood. On many Macca's postcards are labels of return addresses that include various correspondence schools that Macca has created as a front. The addressees range from a professional golfer and Oregon Ducks football coach to Hopkins herself. The cards are sent out incomplete with a request to be completed in some manner. Unlike those sent by McFarland and Ryan/Paulson, Macca has asked that the correspondences be participatory, even if it only serves to reflect back on the artist. It works for Macca, for within the whole body of work we begin to see a complex individual who may exhibit insecurity and aggression, yet also has a capacity for respect and humility. Given this range, this becomes more than a "Two Man Show" in more ways than two. And while there is no doubt that mail art in general has a social component, whether it be a show of gratitude, generosity or public relations, we eventually come to view Macca as more like a jester. Maybe. Because that’s what a jester does, blurs truth into folly, willingly plays the foil, seemingly at his own expense, and then lands a jab. We may even come to believe that both his snide commentary about other artists while asking outside professionals to participate in his art is Macca's way of showing respect for all of everyone's accomplishments, even if some of it seems back-handed. However, the postcards sent to the gallery represent another aspect of Macca's perpetual dilemma: sending them to someone who may help his career, no matter how genuine the intent, carries an implicit subtext. And it can be said that the same holds true for the other artist's postcards and mail art. Not that this is necessarily a bad thing, for it is understood between all parties that this may be part of what is occurring. Yet, the trick is doing it in a way that is memorable, which is what Hopkins is representing as her own subtext in her multiple role of curator/recipient/participant. Otherwise, there is nothing unique in "just another mail art exhibit." For that matter, by adding the other artists and choosing to exhibit the abstractions in the front room, Hopkins' intervention saves Macca from being just another (self-) deprecating artist. Is this too cynical of a read? Again, I defer to Macca, for I trust he would see this particular rabbit hole as neither extreme or over thought/wrought.

Even so, others have wondered if Macca, being so unpolitic and self-disclosing in these small pieces, might be cutting off his nose. The man can paint, so why expose this other side? Because everything is inescapably encoded with a self-interest, and recognition of this is counter-intuitively liberating. Likewise, when we see the little manger scene on which Macca has painted his name over the name of the baby Jesus, he speaks to the pretense of humility we hide behind, to what we deny or ignore of our doubts and inadequacies in front of others, including our secret belief we are more deserving, more talented. To not trust and exclude, to fabricate meanings for our fabrications, or, to hide behind theories and rationalizations, these are our sins, and if Macca is unafraid to expose these truths, then, like Jesus, I suppose he is also prepared to die for exposing that part of our nature that is inescapably abject. Two Man Show @ Art Gym Tuesday - Sunday Noon to 4PM | Through May 18 2012 BP John Administration Building 17600 Pacific Highway (Hwy 43) Posted by Patrick Collier on May 01, 2012 at 21:02 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |