|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

An Interview with B. Wurtz

AB: Hi B! I was lucky enough to hear you speak the other night at PNCA, which was amazing, so thank you for that. BW: Oh, you're welcome. I thought it went well. AB: I wanted to ask you first off: how does humor play a role in your work? BW: I think it's definitely there. People talk about the humor in my work, so I think it's definitely there. I really enjoy humor in life, so somehow it ends up in the work even though I don't deliberately intend to make humorous pieces. AB: Really? BW: No! (Laughing) I don't! But I like that people see it in the work. AB: Because it seems like there is this tongue-in-cheek, rather sly attitude hovering about your work, almost a sort of childlike bravado. It often seems as if you are trying to overstep some boundaries just to see what might happen or whom you might be able to provoke. Each formal experiment seems like a prod to your audience which says, "What if I do this?" BW: I think that is very well put, because I do mess around with the conventions of art. Years ago Dennis Cooper wrote a review of one of my shows and said that very thing, that I kind of fuck around with convention. AB: When I consider your body of work as a whole, I see these questions as an issue of perspective. It always seems to be the way in which you view the work, whether it be through the lens of photography or the arrangements of colorful everyday objects into lyrical sculpture, it always seems to be perspective as the provocation of a different way of thinking and looking. BW: I strive for elegance in the pieces. I feel like that is part of what you are picking up on. You seem like my ideal viewer, because I want people to see the work as humorous and a little bit disconcerting, maybe, but I hope they see the beauty in it too. AB: In your talk, you mentioned going to the MET, and upon seeing an entire room of some of the big AbEx paintings, feeling as if they were saying, "Pay Attention to Me!" It seems as if you are trying, in some ways, to create the same effect with these objects which could be seen as mundane but could be considered beautiful if you paid attention to them in a different way. BW: Yeah, I totally agree with that. AB: Do you ever make work out of anger? BW: Out of anger. . .wow. . . what an interesting question. . . I don't think I do. It's not that I don't have anger. But, on the subject of anger, I think I learned long ago (and this is completely from observation) that the worst thing that can happen to an artist is to get bitter and angry. I told myself that no matter what happened that I would not let myself do that. It doesn't mean that I wasn’t frustrated, because I did have a lot of years of struggle and times when people just did not get my work. There were some people that always did get my work, and they were people that I really respected. And that was a wonderful thing. But it didn't take away from the reality that I was being ignored by the main art world, and I was having financial problems. I don't mind saying that; I think it's interesting. With my teaching, I think it's interesting for my students to know that it's not always easy being an artist in spite of the way it's presented now. It's a really tough life, and I had financial difficulties, but I stuck with it. I feel like I'm an example of perseverance and being a bit proactive. AB: No, I ask that out of the sheer curiosity pertaining to the humorous part of things that seems to take a stab at certain conventions. It not that I see anger in the work, but that I wondered if maybe the impetus for some of it might have been out of anger. BW: Oh no, I see what you're saying, but it was more like jabbing at something more playfully. Because I love art, and I don't deny that. When you mentioned the big paintings at the MET, I want to go see work like that. I think a lot of people work well within the conventions of a standard, stretched canvas on stretcher bars. But for myself, I just had a different way of wanting to do things. AB: Can you describe your process of making? BW: You mean like how a specific piece evolves? AB: Yes, do you notice a pattern in yourself as you make work? Is it different with each piece? BW: It varies somewhat. People are interested in that question. I think for any artist people are interested in that question. I can kind of describe it. As I mentioned in the lecture, I had limited the found objects, and I got on this theme of food, shelter, and clothing which had to do with basics of existence, daily life, that kind of thing. So I sort of had a subject matter in the back of my mind, so I wasn't grasping for subjects. I think this is pretty typical for most artists; they kind of have something they do.

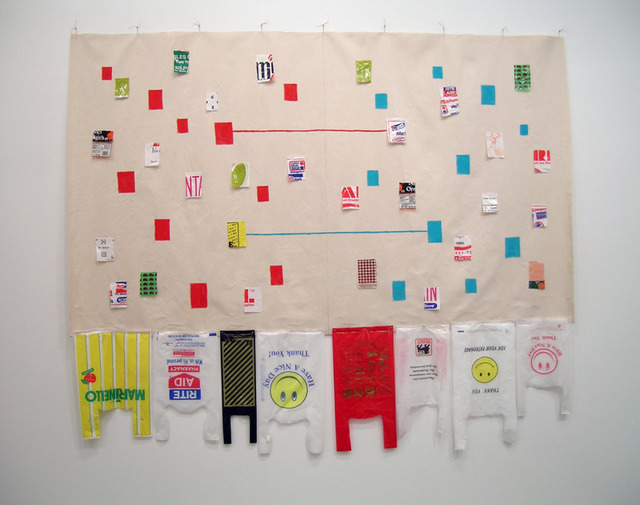

BW: I think I do deviate somewhat, but I think I knew that there was going to be this enormous palette of found objects, and I felt a little overwhelmed. How am I going to deal with this? I think putting the limitation was an advantage in that it made me need to put more effort into what i did with them, the formal aspects of the pieces, the composition. AB: Was that why you mentioned in your talk of not really relating to other found object artists? BW: Yes, I feel like often so many objects are used and often the effect is to abstract the object so that they lose their identity. I just felt that, for me, that didn't seem to work. That isn't to say that it wouldn't work for someone else. AB: How did those limits come about? Do you see them as existential or philosophical limits? BW: Yes, I think there is a philosophical component to it definitely. I'm not very interested in theory. I'm not even very well read in philosophy, but I did realize my work has a lot to do with phenomenology. Stuff that I was interested in didn't have to do with transcending the world, it had to do with being in the world at that moment. And that is philosophical. I mean, it is very related to what is usually termed eastern philosophy and the people that have reached so called enlightenment. My understanding of that is that they have learned to let go of preconceived ideas in order to be in the present moment, in the here and now, in the world exactly as it is, not as one wishes it to be and all of the things that complicate and make our minds chatter all the time. I am not saying that I am enlightened. But I am interested in that concept. In terms of my art, the idea of the here and now had to do with very simple objects, and these are the things that have to do with humanity period. One of my students was pointing out to me the other day that the objects I use are objects used by everyone; they are not related to class. Everyone needs to eat, and everyone wears clothes, and people live in houses that are generally constructed in the same way and serve the same purpose. It is sort of a philosophical basis. BW: I really don't think it changed much. Some of it does have to do with geography in that some of the plastic bags I use have New York addresses on them. I was certainly aware of that, and I like that; it's sort of a mapping of where I am. So, in a sense that makes it geographically specific, but on the other hand, there certain points at which I make little decisions about what the rules of the game are, and this might not be so obvious. But I think I would basically make the same kind or work wherever I lived. AB: I also wanted to ask you about the few instances when text comes into your work. When do words need to come into your work? It seems rather rare. BW: It is rarer than it used to be. I was definitely interested in art that used text. It was one of my interests and clearly I was absorbing that kind of work. I think the reason that there is less now is that I started liking the idea of trying to do what I was doing with text without it. The text now is from the yogurt lids and the bags, but I don't do so much of my own text. It may appear. I haven’t decided never to do it again; it just naturally started to happen less. AB: Despite the unnatural nature of your materials, nature always seem to be referenced. Is this intentioned as commentary or is it simply a formal choice? BW: Yes, you are right about that. I think it is something I can't help. I love nature. I don't use it as subject, but somehow it has gotten in there anyway. People have commented that my wire sculptures with the curving wire and the mesh things are like floral or plant forms, and I know that is where those shapes come from. I definitely feel like the curving wires are branch-like. So yes, I do reference it, and it's intentional not so much in a deliberate way. It just sort of happens because it's something I'm interested in. AB: When you see it happening, are you content with it being seen as such, as nature referenced? The reason I ask that is because it could definitely be seen as being quite a loaded commentary on the state of the environment, with the plastic bags formed into the shapes of plants and the like. .

BW: I am super aware of the environment and concerned about it. But it's not part of my subject matter. Not really. I think it can't help but be there in a way because I am using things that could be discarded or recycled; I just happen to recycle them into art. I am kind of an environmentalist, it's just not really part of the work. AB: What is your ideal experience for the viewer to have when looking at your work? BW: I think it would be kind of what you said in one of your very first comments. I hope that people would look at the objects in a new way and realize how often these objects are ignored. I hope the work makes them smile. I like it if people see some humor, and I hope that they see a kind of elegance that could be weirdly calming. Roberta Smith called me a classicist, and I am totally happy with that, because I think I am, completely. I feel that within certain classical things there is a calmness. AB: The work is often poetic. . .I was wondering if you read any poetry. . . BW: I don't read that much poetry, but I'm completely in awe of writers, and I am interested in poetry. I tend to more be interested in prose that is poetic. There are some writers in particular that I am always drawn to, like Peter Schjeldahl and Bruce Hainley: writers that also write poetry. I am completely into words. So I like it if you would see the work as poetic. AB: Have you ever thought of giving up on art? BW: I have in the past, yes. It wasn't very realistic. I had a teacher at UC Berkeley, my first real art course, called "Materials and Methods in Painting". It was taught by an artist named Jerry Ballaine, a west coast artist, and I never forgot him saying to the class: "If there's anything you can think of doing other than be an artist, than you should do it because it's a really tough life." AB: They say that to all of us don't they? BW: Did you hear that too? AB: Yes! BW: And I never forgot it, and in my moments of frustration in my life, I really wished I could just walk away. But I feel like the older I get, the more I feel like life is about each of us learning who we are and accepting that. I made some attempts, but not really, because what would I do? AB: Did studying music influence the way you approached art? BW: Yes. I began studying piano when I was in fourth grade, and I always enjoyed it. I would play and sight read, and later I would compose too. When I decided to take piano lessons again when I was older, around the time of high school, I had a much more serious teacher. She was an accredited teacher, and we had auditions at Music Academy of the West. All of a sudden I was in this thing. I was just going to take piano lessons, and I was suddenly in this serious world of music, going and doing auditions and stuff. But she started teaching me more things about music like phrasing. Before it was very basic: learning the notes and playing them. But learning something like phrasing really changed the way I understood and played music. There were certain ways to press the keys and move your hands so that you would get a certain sound from the keys, and when she began to teach me these things, I really thought to myself that it related to art. I thought that I could use that way of thinking to influence the way I made art. I realized there was a lot more subtlety that could be a part of art. AB: So this is kind of back to the work itself. ..It seems like your making process involves a sort of fleshing out of an idea in sets or series. How do you know when those sets or series are finished? How do you know when something cannot be made in another form?

AB: I think you might have touched on this a bit, but I would like you to expand on it: what is the difference for you for a piece to be on the wall versus on the floor? Or pieces that do both? BW: Or a pedestal, or a shelf. . .I used to make paintings when I was young. I made oil paintings, ink, water color, drawings. I think the wall pieces come about because I still have that in me, that interest in painting. I don't literally activate a space the way Richard Tuttle does in an installation, but I really think about a room where my art will be seen, so I like to use the walls. I just find it interesting, even in terms of the way one would arrange something in one's living room. I'm interested in the way things look on the wall; there is the flatness of the wall combined with the experience of walking around something. And then there is that question of whether something will sit on the floor or on a pedestal. AB: What is the difference in the experience in making something that will sit on the floor or hang on the wall? Do you make it on the floor or on the wall? BW: I usually make the wall pieces on the floor, but I am picturing them on the wall. I tend to let myself use color more for the wall pieces, painted elements I use on wall pieces. And in my experience, that rarely works for me in three dimensional sculpture. I don't know why. I know some people can do it: put paint or color on a sculpture. For me it's like gilding the lily or something. It's not that the sculptures don't have color, but it's usually the color that is already in the objects.

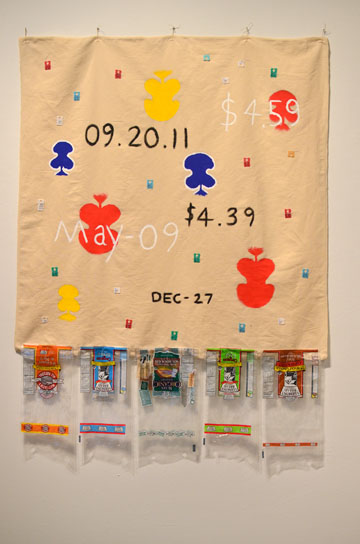

BW: To put the paint on the canvas? AB: Yes, you've mentioned that you've made paintings, but is painting a different kind of making process because you aren't really working with something that already exists? BW: I am interested in the canvas as a material, almost as a sculptural material. Even though it's flat against the wall, it still has a depth, and I've made a lot of works where there are loops at the top and the entire piece simply hangs on nails, so it's loose. It has some depth, whether it is waves or wrinkles. So I'm interested in the canvas as an object. I'm interested in the fabric. I've done pieces with buttons on the canvas, because buttons normally are sewn on a piece of cloth. When I add the paint, I'm really thinking of paint as referring to a traditional painting, but only to an extent. A piece of cloth on the wall references a painting, and it's logical there would be paint on it. I am interested in color. With the sculptures it just doesn't usually work. The color has been the thing. So the paint on the canvas, yeah, it's interesting to think about. . . I like to be almost objective about myself if possible. Like, why do I have the need to do this stuff? It fascinates me. Why did I need to do this all these years? AB: When I look at certain of your pieces, this one piece in particular, two different sets of materials (the plastic bags and the paint) are linked to one another by their own material. I think of these materials as acting as foils to one another. It's the same sort of idea as art and the world being one and the same.

AB: I feel like if you just keep making what you're making, it will figure itself out. BW: Well, hopefully. There is always the question of running out of ideas. I am sure every artists has that panic sometimes. AB: I think it depends on the way you make and conceptualize. When you look at your life's work it seems as if one thing leads to another. BW: I think it comes from that place of trying to be objective about oneself. I saw the show after Matthew [Higgs] had installed it. I felt that it was so weirdly consistent. But I was kind of relieved to find that I didn't repeat myself, that things changed and evolved over time even though it was very much part of the same central impulse, yet it didn't repeat itself. It was really kind of a relief, and that makes me more hopeful about the future. Hopefully it will continue. It will be me, but it will evolve. AB: Which artists do you relate with? BW: Definitely Calder, who isn't often mentioned by reviewers, but I really loved him as a child. I never really thought about Calder as having been the inventor of mobiles as a kid. When I realized this it really astonished me. I still just love seeing his work. Marcel Duchamp. I went through a very heavy phase of being fascinated by Duchamp in the early seventies. He was a big influence. Duchamp has always been important, but I don't think he was always in such high esteem as he is now. Warhol. I still am fascinated by his work.

BW: It's kind of crazy. I try not to think about it too much. But the reality is, we all need money to live. I am not against selling my work or other people selling their work. I think collectors are incredibly important. I like collectors because i relate to that collecting impulse. Somebody needs to take care of the work, and they step up and do that. It's super important, and that's related to the art market. It's necessary in the same ways that art fairs are necessary. It's not the ideal way to see art, but they are what they are. AB: Has it changed at all since you've been in New York? BW: Yes, it's been up and down. There was the early eighties boom and then the crash, and then there was a huge boom right before the last crash. You remember it. What is funny to me is that I always remained on the outside of it. AB: I was just about to ask you if it affected your work at all. BW: No, it didn't affect my work. It didn't affect me. I was hardly selling anything in the boom times. And then the crashes would come, and it didn't make any difference. Now I'm doing better in that respect, and we're in the middle of a recession. So I'm not quite in sync with it. AB: Do you have any advice for young artists? BW: Ok my advice is kind of what I said earlier. I think the most important thing for an artist is to really try and delve in to find out who they are. If that means being able to walk away from art, then they should do that and not worry about it. If it means that they really need to make art, then they will figure out how to do it. It may not be easy, and we all need money, but money is not the most important thing in life. It's only money. And I see this: people do figure out what to do. And always, the work is most important; never lose sight of that. Even though we have to make a living and hopefully even sell our art. I think it's better to never expect to make a living from selling one’s work. I think it's healthier. There are many ways to figure it out. Having a day job can be interesting. It's not all bad. That's a lot of advice, isn't it? There was a period in time when it seemed like there was an expectation that you would come out of grad school and immediately have a show. Like the dealers were going to the schools and taking students right out of school. That was a little unrealistic. I think it's better to be patient. Of course as artists we have to think about our careers and what we can do to promote ourselves, but ultimately the work is the most important thing. People manage to figure it out. I guess I am saying it could be difficult, but it can work out. And if you need to be an artist, accept it. AB: Thank you.

Posted by Amy Bernstein on February 26, 2012 at 23:13 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |