|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Interview with Chris Burden

Gary Wiseman: Let's start with the Three Ghost Ships currently on display at the Portland Art Museum. Will you talk about the development of the project? How did it begin? How long did it take? What were the challenges? Chris Burden: Let's see. The Ghost Ships. They came about by being asked by Mary Jane Jacobs who had been chief curator at MOCA in LA but was now working in Chicago as an independent curator. She was in charge of the Spoleto Music Festival, the art component of it, in 91'. She invited 20 different artists to do projects as part of the music festival, I was one of them. I had been conscious of this boat designer Phil Bolger who was known for making these seaworthy small boats that were ocean capacity and were real simple to build. He was an anti-yachting kind of guy. So I proposed that they build three of these boats, using a local boat builder in Charleston, and that they would sail to England without sailors that they would be robotically controlled with solar panels and GPS and they would carry tea from Charleston, South Carolina back to Plymouth England. So that was the plan. In actuality, as things develop, they didn't have enough money to see it through, therefore it has never been done, but they had enough money to build the three boats and they were willing to display them in the Charleston art museum and we would have one rigged up so that it would simulate what automatic sail handling would be. It was a total dummy in the sense that the boom went out, the boom went in, and the rudder moved occasionally, the sail furled or unfurled, and there was a GPS, but by no means could you put it in the water and set your latitude and longitude and sail to Plymouth, England or off to see Hawaii (laughing). It was just for imaginary, you know what I mean, for you to imagine it.

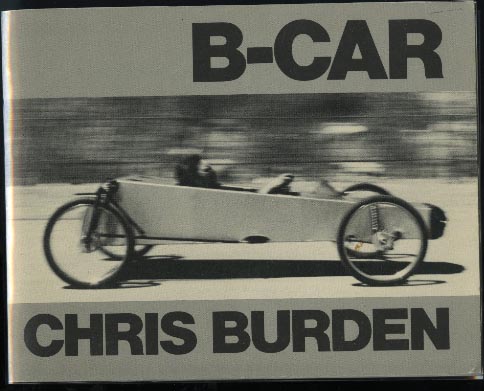

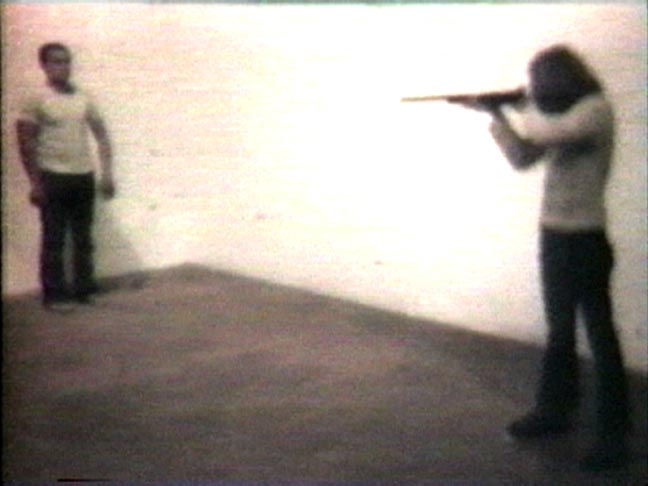

CB:Ghost Ship was a further development of Three Ghost Ships. Again I was asked by a different art group, it was Locus +, based in Newcastle. They asked me if I wanted to redo it because there was a tall ship festival and they could get some British Heritage money to do this project, and would it be Ok to do it with one boat instead of three because it was a different thing now, we weren't trying to move tea, we were just trying to make a sail boat that sails without a crew. This is more complicated than a gasoline powered or a diesel powered vessel or an electric powered boat because you are trying to integrate the ability to tack, you know about sailing right? You have to tack and you are trying to get to a point but to tack to get there you have to integrate the different elements like wind speed, and wind angle. It's theoretically possible I believe, I don't know of anyone who has done it yet. I know there is a little contest of model sailboats in England that was approaching that but I never really followed up on that. The Ghost Ship was semi autonomous, in other words you couldn't really put in latitude and longitude and there were British Maritime laws and we had to be on a mother ship, basically it was a giant radio controlled sail boat. You still couldn't dial in the latitude and longitude but it was a step in the right direction. They were both about the same theme. I believe it's possible and it will probably happen someday because it makes sense. Why wouldn't you want a freighter with only one or two crew members on board? Why wouldn't you use the wind to sail across the ocean? I don't know what else to say about them. The Three Ghost Ships are up in Portland right now and the Ghost Ship is stored on the docks in Newcastle and we're still trying to figure out what to do with it, whether restore it or to bring it home, they're two different beasts. The Ghost Ship looks like a Viking ship it has the abstract, its almost double ended, and its thirty feet long. GW: Will you explain how you progressed from your early performance works like Shoot or White Light/White Heat to a piece like the Ghost Ship? Are you asking the same questions in your work now as you were then? What kinds of questions are you asking? CB: In a certain kind of sense I am trying to push a limit. I did about 70 performances and I thought of myself as a sculptor too. That is how I got into performances. I think the first time, after graduate school, that I didn't do a performance was the B-Car. That was a change in my career because I was supposed to go to Europe and do two performances, but then came up with this idea of building a car that I could build myself, that would be revolutionary, and showing the car in one space and then driving it to the second venue in Paris, where I had a show, would constitute the "performance". That's how I got there. Yeah, I think there is a question about where the limits are and the B-Car was tiny, I could pick it up. I could hold it over my head. GW: When and how did you realize that you had come to the end of your performance work? CB: In terms of the end of performance, I don't think there was an end, the B-Car was the beginning of the end. I certainly did performances after that. It was sort of a gradual process where I sort of shifted over and gradually started making objects and doing installations too. During the late 70's to the early 80's I was doing installations and sort of shifting over.

CB: It was a smooth adjustment. I did a performance a couple years ago that was video taped, but it's a rant, something I did in French, I am sort of ranting in French, there's my head in a bubbling Jacuzzi. GW: Oh yes, You are wearing goggles. CB: Yeah. That was a performance. In a certain sense even more of a performance than the early works because it is theatrical.

CB: I don't know. That's a question I can't answer. I mean, I know that people do them. I'm aware that there is certainly a strong . . . but I don't know how to give you a judgement analysis of where its at. It's not my interest now. Most of the people that were doing performances when I was doing them aren't. Marina Abramovich is an example of somebody who is. I am not particularly interested, It seems like something different now. You know I am not in touch with people who are doing performances, I am not part of that milieu so I can't really answer that question. I just know that people still do them. I read about it and hear about it. GW: It seems like you are acting more as a director of machines now and that the machines are proxy performers. CB: Yeah, objects that are somehow performative. I think that machines in general reflect their creators and are proxy performers. GW: Extensions of the body? CB: They're extensions of the body, that's how we use them, but they are also extensions of the people who build them. You know, their mindset or their cultural point of view. May be less so difference now than before, I mean the difference between a German car and a Japanese car is probably less so now than it was 40 years ago, do you know what I am saying? There is a kind of cultural smearing of technology but . . . you know, people say, 'Don't buy a Chinese bulldozer, that ones no good! Cheap steel' [laughing]. GW: In 2008 you completed a 65-foot skyscraper made out of Erector Set pieces called, What My Dad Gave Me. Would you be willing to talk about your dad and or family and how he or they influenced you as an artist? CB: Well, my dad was an engineer. And he was influential in that we would talk about politics and world events and even engineering sometimes. I think it was kind of an homage to my father for sending me to good private schools and paying for a good college education and encouraging me. So it's more that he gave me the tools to conceive of making something like that, and the confidence to do something like that. GW: I know you studied physics and architecture as well...? CB: I went to Pomona College and they didn't have an architecture program so we took art courses and math courses and physics classes. That was the mix. So I quickly gravitated more towards sculpture classes than I did high level calculus classes and stuff like that. And the physics kids that were there were really creme de la creme physics students. I wasn't. I worked in an architectural office back in Cambridge, Mass one summer too and didn't like that. So when I came back I decided to change my major to sculpture and just make sculpture in the sculpture department and not deal with the calculus classes. But I was interested in physics in general. GW: Did that interest come from your dad? CB: Oh, you know, partially but I think I just have an interest in science in general, science and engineering. It's just part of my general interest. I don't know if it did come from my father to some extent.

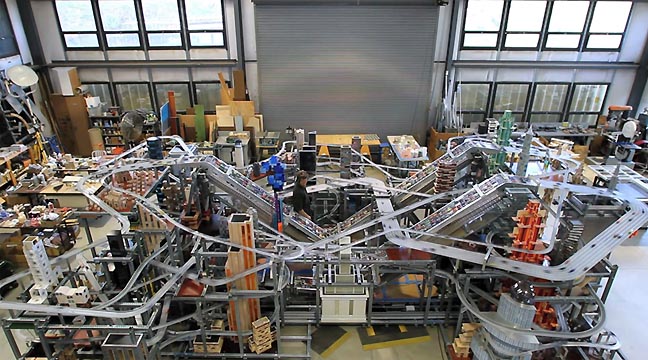

GW: What My Dad Gave Me, is an extraordinary piece. The video documentation of its stainless steel components interacting with the light of the city makes it seem as though it is alive, almost animated. Was this phenomena inherent in your design? CB: I knew that was a powerful part of it because, first of all, I manufacture those parts myself. They are a replica part of an early Erector part that was made in the early teens. It was made out of just stamped steel. I actually used some of those in my early bridges but the problem is they rust and they are also in terrible condition and they got more and more expensive. So at some point I made a series of bridges, an edition piece, and we produced the dies to match the old parts but we stamped them out of stainless steel. And we do something, it's called electro polishing and it's sort of a misnomer because its not polishing as such. You actually dip each individual part in a solution and then run a current through it and the current pulls the nickel to the surface and erodes away the iron. So that's what deburrs it. It sort of etches it. And the nickel comes to the surface which is really harder, it's tough, and that's what makes them really shiny is the nickel that is brought to the surface. It's something that I like because that metal now is really weather resistant and tough. It's a harder surface. I have had parts outside for years, these you just wipe them off with your finger and they're shiny. GW: It's a beautiful object. CB: Yeah and it glows. When we first put it up it was out at a trucker's yard where we assembled the components, the big chunk components. We had to put it up out there and it glowed like phosphorous especially when there was a green hill behind it with the light hitting it full on. It's just blinding actually. It works really well. In Manhattan it's a bit harder because of all the buildings but it still really can glow on you. GW: You haven't shown it anywhere else, right? CB: No. There was some talk this year of it going up at MOCA in LA off Grand St, it just got prohibitive financially basically. You need a 250 foot crane to lift the building and all of the sudden you have a half million dollar install. Gagosian Gallery chose not to pay for that. I understand. Someday it will go back up, somewhere. GW: I've noticed that movement and motion appear frequently in your work. From the early body-based performances to the almost geological time of a work like Samson (1985) to the perpetual motion of your most recent work Metropolis II. Is movement and motion a byproduct of your work or is it central to that which you wish to communicate? CB: I think motion is a part of modern life and ironically it is sort of what steered me into performance. I started out being trained as a minimalist, those were all of my teachers. They were trying to get to the essence of something or the core of it, the reduction of it or something. When I was first studying sculpture, as opposed to two dimensional art, I noticed that sculpture would force the viewer to move. I understood that. It's just that simple. You walk around a piece of sculpture look at it from the sides, the front, the back. The idea that may be the art was the movement not the object, that was how I finally got to doing performances, that you could do something, that you didn't necessarily have to make an object to make art. That was something that came out of minimalism for me. I think a lot of those works that I have made since then, the B-Car is a good example, but there were other pieces too there was the C.B.T.V. (Chris Burden Television) which was about a machine and also it involved movement. And the Flying Steamroller . . . GW: So many of them. . .

GW: The Flying Steamroller? CB: Yeah, I just got an email. It has a leaky hose or something. GW: I haven't heard that. CB: Is that right, Katy? [speaking to his assistant] I guess we have to see if it works. GW: You have shown in Portland previously at PCVA, a long time ago? CB: Yes. A long time ago I did an installation with Alexis Smith. We made a replica of my studio in Venice. GW: And lived in it for awhile? CB: Kind of, yeah. We lived in it for a week or something like that. We treated it like a residency sort of thing. GW: There is a rumor that you had a little scuffle? CB: I did afterwards. Some drunk guy was in the room, we were just on our way out, and he was pulling the sink off the wall and smearing paint all over the place and I got in the fisticuffs with him. GW: Metropolis II is overwhelming even in the video documentation I have seen of it. I have imagined that it might be more overwhelming in person than actually being in a city due to the concentration of activity provided by scale? Now that it is finished what is your experience of it? CB: Yeah, the Metropolis should be interesting to see when it's shown to a huge public. I've shown it here to two, three hundred people when it was in my studio before it was shipped down to the museum. It is going to open in about a month or so. GW: How long will it be up? CB: Well the loan from Berggruen is for ten years. GW: Oh, so it will be fairly permanent. CB: Yeah, I don't know what happens after that. Nicolas Berggruen owns it but he has given it as a long term loan to the Los Angeles County Museum, but then what happens to it is up in the air. Unknown. It does overwhelm you, more so than the video. It's pretty loud and there is so much activity that it produces anxiety when you're trying to watch a car but you can't, they're just zooming around like crazy. They are having real problems putting all the chunks back together. They really have to be precise, within several thousandths of an inch, but they're working on it, they'll get it back, it's just a matter of time. GW: Do you feel good about it? CB: Yeah! I'm looking forward to it running again. I think it will be well received. GW: You once said that you are interested in, "What constitutes distance". Would you talk about this interest? CB: Well, There's physical distance, especially living in LA, but today distance is more about time than physicality, so it's not how far something is from me physically its how long it takes to get there. Some places are a lot more remote than others. I had this idea which I haven't really acted on, which was to make a three dimensional, ever-changing map of the city. Well, you could do it in real time, but the time it takes to get from A to B, for example in Los Angeles area you could imagine that the city would grow huge during rush hour or traffic jams; a traffic jam could be a big spike, something that would come off this big glob and then during certain times in the wee hours of the morning the distances would shrink because the time would shrink so if it takes half an hour to get somewhere and then it takes two hours and a half then the city is much bigger. If you can imagine this three dimensional just glob that was just expanding, contracting, morphing, you know going in, like a giant amoeba that was just pulsating. So I think that sort of tells you about distance. Metropolis II is a good example too. The cars are going at a scale speed of 230 miles an hour. Of course you can't drive that fast in LA, but if you could, imagine how that would shrink the city. Even though the miles were the same physically the time change would be so radical it, it would be different. I'm sure that is the hope of modern air travelers, that the airplanes go faster [laughing] haven't seen much change in airspeed in the last 40 or 50 years unfortunately but I was hoping that the Concord would catch on.

GW: How do you go about navigating power structures in order to get what you want? CB: Well, I mean you have to be, I remember during exposing the foundations of the museum Frank Gehry's engineer was consulted by the museum curators as to the structural feasibility of undermining those three columns and he said, "It's such a stupid idea, why would you want to do that?" And I said, "Well, he's the wrong engineer, let's get another one." So we got another engineer and the guy said, "For every time you dig down past the footing you need to replace the whole column and the concrete footing on the outside of the building." And I said, "Well, that's way, you know," and I looked at the curator and she said, "Your project's only budgeted for $10,000 and, you know, each of those columns will cost more than $100,000 each to put back up on the outside of the building." So I said, "Well, that's not happening. Let's hire another engineer." And she said, "The museum will not hire another engineer, Chris." And I said, "Huh, who's the museum, huh? Who's the museum? Are the Bricks talking to you?" [She said], " No, the director will not hire another." And I said, "Oh, okay, alright, alright. Let me talk to the second engineer. Let me talk to him face-to-face." So I met with him and engineers think in a very linear way and they, it's kind of like if you don't ask they don't tell you the other answers. So he said, "Well, when you have a block of concrete sitting on a pile of sand and you undermine one side of it straight down, you know, make a cut straight down on this pile of sand you undermine some load-bearing capacity of that block because the load goes out at a 45." In other words, if you dig away from the bottom of this block of concrete at a 45 degree angle you don't undermine any of its load-bearing capacity. So I said, "Oh, so if we dig our trench and we go down to the footings and then we dig our trench back at a 45 then we yeah, so then we wouldn't need the three columns on the outside?" [He says],"Correct." So I mean there's an example of how, you know, the museum was ready to throw in the bath water, or the towel, or whatever it is, you know what I'm saying. GW: So it's about being persistent? CB: It's about being persistent and then trying to find a compromise, too, that doesn't violate your principal, or your basic idea, [but that] still deals with the reality of the situation. I mean, the compromise of the angle coming back at a 45 to the back of the bottom of my little trench as opposed to straight down, that's a compromise I can live with. And you still got to go up and poke your finger under the foundation. So, I mean, you know, that's how you do it.

CB: Oh, you know, I don't know, to make art, probably. Um, to keep myself interested, to do things that I think are interesting. And to see them realized, you know? I mean Metropolis II was kind of a mega-project, you know? Yeah, it took four years, that was only a little long. And, but you know, I mean I was installing it and they were having some problems lining things up, and so I was told by the museum staff that I'd had my three months and da-da-da-da and they said, "Look, well, it's not open-ended." And I said, "Well, it kind of is. Sorry to tell you but, you know, what are you going to do, stop after three months? Go back to Berggruen and say, 'It can't be done,' or something?" I mean, I didn't think it was going to take four years, but when the museum gets into making art it is open-ended and that's a problem institutions have, I think. You know? Cause they're not in the business of making art. It's a different ball-game. GW: You taught at UCLA for many years. Will you talk a little bit about your teaching career and how it informed your work as an artist? Do you miss teaching in a university setting? CB: Yeah, I taught at UCLA for a real long time. 26 years, or so. You know, it was good at the beginning. It gave me income. It enabled me not to be 100% dependent on sales, you know? It gave me a certain freedom, too, even though you had to go teach. I'm not sure how much it informed me. I think, you know, finally it was a detriment to making my art, and so, to go to your second question, no, I don't miss teaching in a university setting. I taught enough. I gave. I kind of wish I'd quit a little bit earlier, you know? But I didn't. GW: The next question is about collecting? CB: Yeah, you know, I collect a lot of stuff, that's for sure. And I don't always know what I'm going to use it for. So sometimes I just have stuff and then, uh, the steamroller is a good example. I mean I bought it, a guy who works for me who's a friend saw it parked on the side of the road and, you know, figured I'd like it and told me about it. I drove out and saw it out by San Bernardino and I bought it. I had different ideas for what I might do with it. And the Flying Steamroller was one of them and that's the one that got executed. But it could have been something else, too. GW: When did your fascination with collecting begin? CB: Oh, well I think I've collected stuff for a long time. I mean for a period during, uh, where I going to school and after grad school, I didn't have any, you know it was hard to collect stuff because you couldn't save it. I'd try to collect things and then storing stuff is problematic, because you have to either pay storage, and then you have to move it, organize it, and so I don't think I really started collecting--well, that's not true--until I finally had a place that I owned and could sort of, well, I wouldn't have to move again. It's space, but its also the idea that, uh, I mean it's hard collecting if you don't have weather protection, you know what I'm saying, you need space and a building, too. GW: When did you get to a point where you could start collecting to your satisfaction? CB: Oh, I think when I first started living out in Topanga, probably. But I collected stuff before then and used it. So that's not really true, but it helped to have a big studio and a place to put stuff. Then it becomes a problem of keeping track of it all. You know, knowing what you have and not forgetting about it. GW: What's your next endeavor? CB: Well, a couple of things. We're working on two or three projects. You know, there's never a break in a sense, it's just the studio got free in the main space, but there's stuff in it now. And then over the next six months or so we're going to start taking a lot of the stuff I've collected and put it on tables and look at it and try to do something with it. GW: No specific plans? CB: No, I just want to look at it all. That's part of it, just seeing what I've got. GW: Have you considered just showing the collections? CB: No, I haven't. That's a thought. I'd never really thought of that. I don't know how interesting that would be. That's a thought. I mean, I don't even know what I have really. I mean I have an idea, but I want to sieve through it and figure out something to make. GW: Well, that's all the questions I have. If you have any other things to add? CB: No, I'm happy the boats are up. Are they up now? Are they showing? The booms are going back and forth occasionally? We spent a lot of time restoring those things, so, I hope they work. We spent about three months stripping them, painting them buying new sails, redoing all the electronics. GW: Were they kept outside? CB: They had been, under tarps. You see, there's your problem with storage issues. You know, they sat outside for 15 years. They all had to be stripped back down to the bare wood and repainted. GW: Was the last time you were in Portland when you had the PCVA show? CB: Oh, I'm trying to think, oh, I think I've been up there since then to give a lecture but I'm not 100% sure. GW: What was your impression when you were up here? CB: Oh, it seemed nice. I mean, I don't know, really, to be honest, when you're on those things you just work every day. It's not like you really get a sense of the city, or what it's about. We just worked our knuckles to the bone and left the next day. GW: Alright, thanks for your time. I really appreciate it. I look forward to seeing Metropolis II and what you're going to do next. Posted by Gary Wiseman on November 01, 2011 at 11:17 | Comments (2) Comments A few comments and further information about Ghost Ships: Posted by: pdxh2o Wonderful insights sir and duly noted. PORT has the best fact checking staff in the world (you). It is always great to hear from other primary sources regarding the projects we cover. Anything else you would like to share is just icing on the cake. -the management Posted by: Double J Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)