|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

2011 Art + Environment at the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno

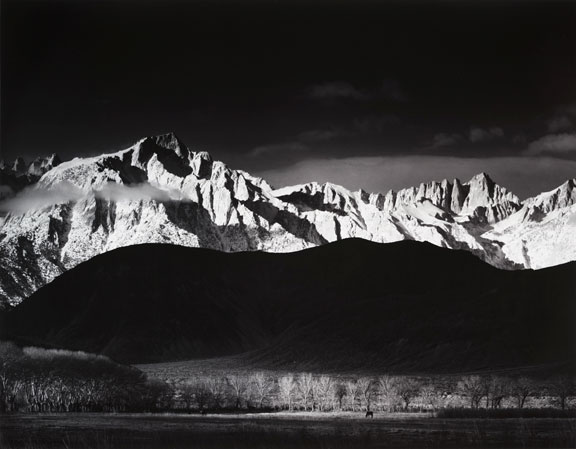

While the influence of human activity on the planet is undeniable, a deeper question, especially for artists, is how does recognition of the Anthropocene era influence the work that we choose to make and experience. One of the opening talks was by Alexander Rose, who is the Director of the Long Now Foundation, a group that constructed a clock that will run for 10,000 years. It is hard to imagine anything that would last that long. To put that into perspective, the oldest language -- either Sumerian or Egyptian -- has only been around since 3,200 BC, or the last 5,000 years. A few of the many excellent speakers at the conference included Fritz Haeg, Thomas Kellein, the director of the Chinati Foundation, the artist Leo Villareal and Patricia Johanson. It was surprising to see the work of Helen Mayer and Newton Harrison, whose works are often so large they might take up to 50 years to complete, but would change the effect of global warming on the watersheds of the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California. It was inspiring to see that artists would have something to contribute in an area that we would normally think of as engineering. A common thread moving through most of the presentations was the idea of time. There is the geological time that runs through the Anthropocene, there is the millennial time of the clock of the Long Now Foundation, and there is a time that exists forever in the fraction of a second of a photograph. Edward Burtynsky gave a remarkable presentation on his work, and the conference itself is accompanied by an exhibition of photographs called ?The Altered Landscape,? which was curated by Ann Wolfe. Even the title of the photography exhibition suggests that we are no longer in a world in which humans have not impacted every part of nature in some way. Landscape, by the very definition of the word, may never have been pristine. So the question facing artists is: if artwork is in some way a mirror to the culture in which it is made, what do the photographs of Burtynsky, Ansel Adams or even Robert Adams say about our time? As I walked through the exhibition, my first reaction was how different a medium like photography is than our experience of nature. A photograph, often exposed for a fraction of a second, is frozen in time forever. Bounded by a rectangle, some elements of nature are included within the frame, while others are excluded. Nature on the other hand is always moving and never frozen. Whether it is building up or eroding away, it is never still. How often have we looked for something that was in photograph but does not exist anymore? Nature is smooth and unbounded, while photography is discontinuous and fragmented. Like every other art form, especially today, it is a good habit to articulate that photography should never be confused with truth. There was a funny moment when the photographer Subhankar Banjere related a story about a curator who came up to him one day and said that if he wanted to get his work shown in museums then he should not take pictures of landscapes. Banerjee smiled politely and continued making his own work. I was not sure what the curator in Banerjee?s story was driving at; maybe it is that people who go to museums only want to look at themselves in one way or another? Is art only about vanity? Or maybe taking pictures of landscapes might be too easy? These are important questions because they set up the framework for how artists might use their work to explore our relationship to the natural world by using photography as an example. One of the photographs in the exhibition Altered Landscape was Ansel Adams? Winter Sunrise from Lone Pine, Sierra Nevada, 1944, which was taken a few years after high school students placed large LP on the side of the mountain. Since the letters are barely visible on the left side of the mountain in the foreground, the photograph was presented as evidence that Adams? photographs were nostalgic or romantic because he refused to emphasize the manmade element. I thought that this reading was a little odd because if he really wanted to he could have removed the letters from the negative. It was there, he photographed it and he did not obliterate it. Perhaps it is more of a question of emphasis. How does living in the Anthropocene define an artist?s engage with nature? It is a useful question, and it can be used to examine some of the dominant issues of the conference and the exhibition. Are artists only to document what we see? Or is what we feel? In what time? Is it today? Tomorrow? Or 10,000 years from now? Are artists like students arranging the rows of rocks to spell LP in Adams? photograph, just declaring our space and presence in the world? Is art nothing more than a collective declaration of ?we are here and we exist?? It seemed like an unspoken question that wove its way through the presentations, silently asking what is the role of the citizen? What is the role of the artist? Which brings us right back to Ansel Adams. Are the photographs of the landscape supposed to be about who we are or what we aspire to be? Is he taking a picture of a physical or spiritual space? I think Adams understood this in a profound way. His answer is obvious. When he walks into these spaces, whether they be landscapes in New Mexico or Half Dome in Yosemite, he is interested not in who we are today but in the potential of who we could become. I think he wants us to look around us and recognize the gifts that we have been given in nature. One gets the sense that he wants us to be worthy of those gifts. I want to finish with a photograph that I have been thinking about a lot about lately, Ocean I by Andreas Gursky made in 2010. The picture looks completely reasonable. Everything seems proportional, and there are appropriate gaps between the land masses. If one was not familiar with Gursky?s work, you might think that he paid somebody on the International Space Station to take photographs of the oceans from orbit. But the truth is that the photograph is completely fake. First, the earth is a sphere, so it is impossible to display it on a continuous flat surface. Rather than a single image taken from the international space station, the work was probably assembled from hundreds of satellite photos. All of the edges between the photographs are smoothed away. The colors are balanced. The space of the ocean becomes continuous. There are no clouds. There is perfect (maybe godlike?) precision. It is at once completely natural and artificial. A space is created that communicates something about the oceans between the continents, even if that actual space could never be depicted that way. Like Picasso said, these photographs are the lie that tells the truth. It is a new space. A new way of seeing ourselves. Seeing the way that we live. It is like a Technicolor panorama where the very finite-ness of these vast spaces reminds us of their fragility and vulnerability. Like the conference, we are each left with questions that perhaps can only ever be answered individually. Is art about who we are or we aspire to be? How do we balance our responsibilities and behaviors between the short term and the long term? Do we have any responsibility to the generations of the people that will inhabit this planet when we are gone?

Posted by Arcy Douglass on October 26, 2011 at 15:10 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |