|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

The Beginning of the End Of Us: a Conversation with Deborah Kass

This interview was conducted via Skype, so picture it.

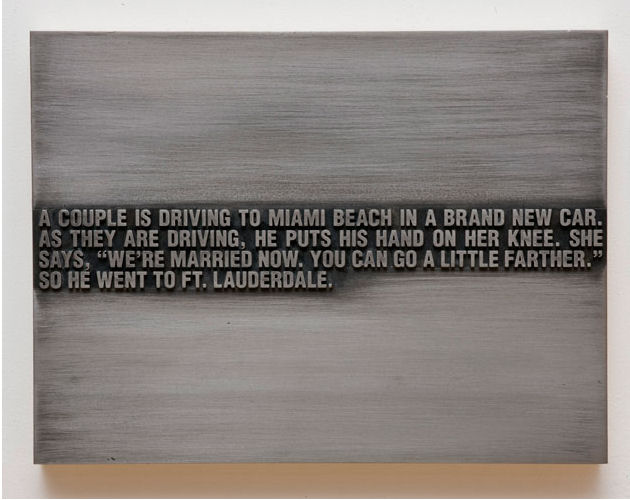

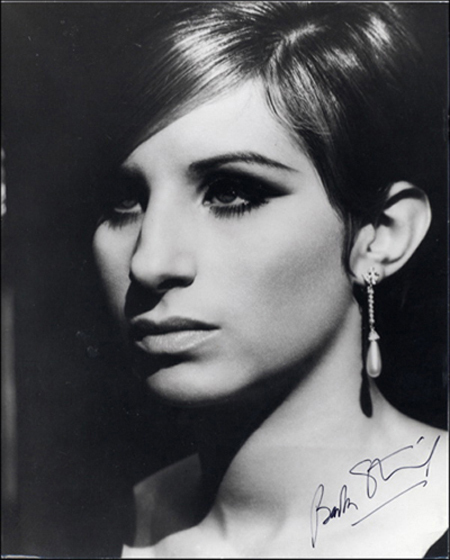

D: Yes! A: Well, it was a great speech. It was very sobering, and I felt that by the end of it we had all taken on a very pointed responsibility as artists and as humans. I felt like I was being called to duty. Deb, your paintings exist in a way that seems to address a sort of societal lack, as if they exist in order to fill a void. They are not only your experience of this world, but they seem to acquire a life of their own as a necessity. What would the world need to not need your paintings? D: Well I think Dionne Warwick said it best through Hal David's lyrics: what the world needs now is love sweet love. I'm being facetious, but I kind of mean it. You know, the world needs peace and to get itself together, but it's not going to, because people live in it. A: That's quite an undertaking: to fill that kind of void with paintings. (music) D: I'm sure there will be more of that, hopefully we can get a Glee clip on. There isn’t anything that I know or that anyone needs to know that isn't found in pop culture, so I tend to reference it a lot. A: What kind of experience do you intend for the viewer to get from your work? D: Honestly, I think it depends on the viewer and what their cultural references are. Now that Glee has come about, there is an entire next generation that will have a present setting for the references that I make. Glee has really changed things. Until Glee, I usually imagine that the people who really get what I do are people my age, my generation; I kind of wanted that. I wanted to paint from my own experience and not pretend to be 25, because I'm never going to be 25 again. When Glee came about an enormous amount of my references became available to younger people. They recognize my references, and that is really a surprise. But they are too young to buy art; they're only about 18. A: How did you become a painter? D: I was always a painter. I mean, I was always an artist, and that just meant painter. A: Were you always satisfied with the work you made as an artist? D: Of course not; I'm an artist. And I'm female, so who could ever be satisfied? It just doesn't come with the territory of either. A: Did you ever feel as if painting was inadequate for a time or an era? As if not only the critical or academic viewing population but the art viewing population in general sort of shut their eyes to it as an intellectually viable, expressive voice? D: Oh yes, I have felt that way my entire life. When I went to college, the idea of being a painter was ridiculous; nobody wanted to be a painter. My first semester I did a lot of conceptual art, but, you know, we're talking 1970. I knew I would eventually get to painting, but painting was so outre then. Even I knew as a freshman that it wasn't cool to paint. And it was very uncool through the eighties to paint. You particularly couldn't be a woman and paint. You still can't really be a woman and paint. So the seventies was a great time for women painters, and that happened to be when I came to New York. I didn't even think about the issue then, or that there would be an issue. But with my generation, the only people who got any attention for painting were all male. There was not a woman of my generation who got famous painting. A: Did you ever feel, as a female artist vying for a respected place in a male dominated art world, uncomfortable appropriating abstract languages of the past while trying to stake your own claims? D: No. It got me in trouble, but I just thought that that was what being an artist was. A: Do you think referencing this history renders it in a different light, changes its context? D: I want you to go look at "The Cube Show", an online art show I curated. It examines the form of the cube from 1963 on, through art history, and demonstrates how the meaning of this form has changed drastically with each artist's usage of it. It is sort of how I see the world. A: Where does the joke exist in your work? What do you think of the comedic element in painting, the existence of the one liner? D: I think if it's good enough for Richard Prince, it's good enough for me. A: Do you ever become weary of having to fight endlessly under the restraints of an identity? Do you ever wish you could work beneath the guise of anonymity? D: You mean under the guise of an anonymous identity? Like under something that would be seen as "normal"? Like being a white man? A: No, I guess more from a place that the work could simply stand alone, rather than it's maker having to fight so hard for her very existence to be considered in the first place. D: My work stands alone perfectly fine. It really depends on the work you're talking about. There are lots of references in all of my work, and it can be used to many academics' benefit. If I was a white guy painting, I'd be painting like a white guy, so, I don't have a problem with that. I have a problem with saying that is all that it is. The struggle was going to happen no matter what I did; that is just how it is. There isn't a female artist in the world who doesn't get called a female artist. That is out of my control. A: Of course. But I mean, in an ideal world that wouldn't be an issue that added to the already challenging task of making good art in the first place. Did you ever think of working under a pseudonym or anything like that? D: Yeah, sure, I thought about it in my twenties. I thought: yeah, I'll work under a male name, and no one will know who I am. And then, one day, I will jump out of the cake, naked, and I'll be me. But, it doesn't work that way. The art world is a community. Everybody knows everybody, and there is no such thing as anonymity. And it's a world where what you are is more important than who you are anyway. You kind of get called what you are, and you go, What? I'm not Jewish? I'm not female? I'm not a dyke? I am. I just can't stand the limitations of those interpretations, because there is so much more to be said. A: How do you recognize a body of work coming to an end? D: When I run out of ideas. A: How has your approach to your work changed over your the course of your career? D: That question is difficult to answer, because it's really about being an artist my whole life. I have bodies of work that absolutely reflect how I'm thinking, the different places where my thoughts have gone. Between the period of my art history paintings and the Barbra stuff, I realized I was sick of talking about my absence. I wanted to talk about my presence. I came up with Barbra, and it was like: Bingo. Between the Warhol work and this work, I wanted to do the same kind of thing, but I didn't want it to look the same. I wanted it be even more emotional. It was also much more about the Bush administration (laughing). It was about politics and emotion. The next part of that body of work has really become more about existential questions. But that is much more life; it is what happens when you get older. It just happens, and then, as an artist, you make work that talks about it. A: What makes words, or phrases, or song lyrics become paintings? What do you require from them to be able to go into the work? D: They have to be brief!(laughing) They have to fit into a certain amount of space, and they have to really be legible. That is the biggest requirement. Five words is really pushing it. If it is too long, then it becomes more about a sentence than an image. A: Yes, but what do they have to do for you? There must be a certain something. Not all words or song lyrics make it into the paintings. You reference the Great American Songbook in past interviews, but not all of those lyrics and phrases would make the same kind of paintings or be imbued with the same kind of emotion or have the same succinct kind of energy. D: That's it. They have to work on all of those levels. They need to be really sincere. Even when they are ironic, like some of the lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, they have to be sincere. It is a sincere emotion that he's describing. Sincere befuddlement, or "I can't believe this is what's happening, isn't it rich?" It has to be that, and it has to fit in a certain space. It has to be one of those things you ask yourself or you say to yourself that is familiar. It has to be really familiar but not as familiar as the title. It's better when it's deeply embedded in the song, and I pull it out. This way it is recognizable yet can't always be easily placed. A: Would you ever consider using contemporary song lyrics? Would anything from contemporary pop work for the current paintings? D: You know, I have been thinking about this lately. There have been things along the way that would seemed to have worked. But, honestly, I am really 1975 and before. It's really a lot of my parents' stuff. I don't know why, but I really am this Great American Songbook thing. Every now and again, I think, my God, I should at least do a Carol King, but I never quite get there. And I always think about Joni Mitchell, and I never get there. I did do Laura Nyro, but that was '69. Part of the need to reference that time in particular was Broadway and wanting it to be Broadway. Then the referencing kind of branched out a tiny bit, but I don't really listen to that in the studio. When I listen listen, I am listening to jazz. A: It's not visual, but nostalgia obviously plays into this process. But the work is not nostalgic at all. D: I think it is nostalgic. It is actually intentionally nostalgic. My work is nostalgic not only for the Great American Songbook, but for Great American Painting. It is really about stuff that my generation considers sentimental. The work isn't sentimental, but we are sentimental about the work from that time; it's the reason we became artists. It's like Elsworth Kelly or Jasper Johns or Frank Stella or Andy Warhol, and that's a big deal in my work. I consider nostalgia a political tool. A: I can see that. Nostalgia is one of the most powerful political tools utilized. Look at the majority of advertising schemes and presidential elections. . . D: Exactly, and I'm looking nostalgically at Post War America, which someone reminded me recently wasn't the best time. (laughing) Of course I know this, but look at what it produced. Look at what the visual culture produced. Look at the music it produced. Look at the optimism it produced in a greater part of the population that had never felt that optimism before. That part of the population was the middle class, when there was a very specific middle class. Taxes were structured to create a middle class, and they did. That is a thing of the past now. A: Do you foresee that recurrence of something great coming out of this era? You claim that the particular era you draw from was one of such strife that people found and developed an optimism to sing and dance about, and that this time is in shambles. Will something have to arise because of this too? D: I don't know how much greatness came from my generation. It was great before my generation. I think my generation is lacking some sort of hard earned vitality. I can't think of a single musician of merit from my generation except Bruce Springsteen; there is literally no one else. I'm 59, but all the greats are 70 or older: Dylan, The Beatles, The Stones. . . I have a feeling that when we look back upon this generation of art, we will be very surprised if 'great' figures in; that is of course if there's anyone left to look. I certainly can't predict what will happen with the next generation. The best thing you can expect from such terrible times is some great art, but I don't know. I don't know what will be left at all, let alone art. I can't believe what is happening in the world right now, which makes me nostalgic (laughing). A: I am strangely nostalgic for that time too, even as I am much further removed from it. That was the time of my grandparents, and it seems that, with their death, something fell apart. D: When did they die and how old were they? In their eighties? A: They were eighty-five. D: Exactly. That is my mother's generation; it's that gang. Maybe they served in World War II. My father didn't, but he served in Korea. My parents were first and second generation immigrants. Three grandparents came from Russia, and one was born here. It was a lot of pressure on those children to be certain ways. Then they produced me, and then you, and well, . . .We have such bad values. A: Many of us do, and we have definitely made quite a mess of things, but I don't think it's hopeless. There is always hope. Hope is always the last to die. D: Notice I'm not commenting. A: (chuckling) A: I wanted to ask you about the presence of icons in your work, because their presence is not only about nostalgia. Andy Warhol of course was one of the greatest artists of the twentieth century. Barbara Streisand was a figure who I believe is not really paralleled today. Her identity and artistic merit seemed to be so pure; she did not present her image in irony or self deprecation. She arrived in the spotlight as a very pure talent, her identity very naked and proud even. I would like you talk about your intellectual engagement with this type of icon. D: Well these are reasons why Barbra was completely radical. She was really radical. Her self regard was radical: the fact that she knew she was so glamorous and beautiful. People like my parents didn't think she was beautiful. The fact that she didn't have a nose job or change her name was huge. Between the nostalgia for the music and movies of my parents' generation, her difference was exceptionally inspiring, because she dug it. She didn't run away from it. She was gifted with her mind and her voice, and she understood the power of her difference. She understood the glamour of her difference before difference was ever something that was valued. And she did all of this work before any academic had dissected or discussed these issues. She made Yentl before queer theory and before anyone talked about drag; it was 1983. She made it in '82 when she was 40 years old. She understood it at 18. She is really a role model of the highest order.

D: You mean like Lea Michele? Well, I think she's a fantastic role model. A: Do you think you play on this nostalgia and these types of icons because we need to feel this nostalgia too, as viewers? D: I think the nostalgia is for the values; it's not for the specific objects or the specific words. It's more about the values that produced those things, and yes I think we need to really think about them. I don't know if nostalgia is the word I would use to describe what we need to think about them, but if that's what it takes to get there, I am fine with it. I think it's the values of that time and that type of entertainment that are so interesting.

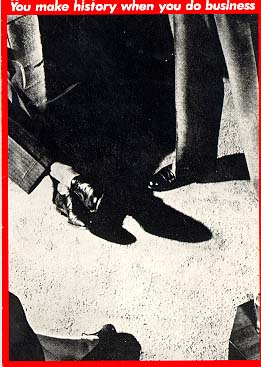

D: I don't really read that much of it. I don't really think there is that much of it to read. There seems to be mostly reportage, which I don't really take seriously. I am really a big fan of the art historians more than I am of the critics. I'm interested in history, not in people's petty hearsay. When you ask me about critical writing, I can only think of the politics behind what actually gets reviewed and published. It makes it hard to take seriously. It's entertainment, and art is pretty much entertainment too. That is realistic. I guess I would put the critics in that realm. I think we're all sort of part of an entertainment industry. I'm sorry to say it, but maybe that is also why I reference Broadway: to point out the entertainment value of what we do. A: I like to entertain the fantasy of the ideal, in which artists' work is separate, at least in some sense, from the market, maybe even if only intellectually. . .I mean, ideally, art often endeavors to challenge ways of thinking, to offer up an experience in a different light or at least someone else's light. Entertainment does something very different; I often think of it as giving you exactly what you want, the unspoken yet understood entertainment of what you most likely already know. This can often grant a bit of respite from the very human existential questioning and crisis that life often provides. I think of art as offering up more of those questions, which is not respite but more stimulation. D: You might want to separate artists from the art world so to speak, but the ones you know, you know because of an art market. It's like Barbara Kruger said: "You make history when you do business." I'm not sure if "challenging" art has any place left, because who are you challenging? A: In the least, you attempt to challenge history. D: Is that what people challenge in art, their history? A: Artists challenge their history in the sense that they are trying to express a way of seeing as well as examine the possibility of creating new language that comes as close possible to accurately describing the experience of what it is to exist in the world right at this moment, which has never existed before. D: I think that is fine, but everyone's experience is really different, and chances are if you're experience is really different than the people who are buying art, then you might have less of a chance to be seen. A: Yes, but the art market is always looking for the newest and the best, for things which it can stand by as increasing in value. In the art world, this equates to timelessness: that which is timelessly good. The greatest work has always been challenging to what came before it as well as the times, yet it was still recognized for its genius. D: Everybody wants what everybody else has, that's all. Nobody walks around and says: I want the most challenging. They say I want a Richard Prince. That's all. People can feel good about it because they think to themselves: this is challenging; they think: this is ART. I'm not sure 'art' as a category is going to withstand much more, because it's so abused. So many people are parasitically and peripherally involved and just because they say it's 'art' gives the thing a certain social importance and a certain gravitas that I don't really believe most of it has. I'm not sure any of it does. I'm not sure I have it. I'd like it to be that way, and I try. It's like Joseph Kennedy said, he sold all of this stocks in 1929 when the shoe shine boy was talking about stocks with him. I feel this way about art. Who isn't talking about art? To me, it's just more politics. The same people get used for everything, and you just wanna be one of those people. I'm trying to be one of those people that is on every list. Then maybe I can get on the shopping list, and you know, your big moment in life is when you can get on the shopping list. Fabulous. Is that what I signed up for? No! Do I need it? Yes. A: What did you sign up for? D: I signed up for an intellectual life. That is why I like historians so much, because they exist in another realm. I am friends with people in their eighties, like Irving Sandler and Robert Rosenblum before he died. I worship these people. These people have seen it all. They've written it all. They've done it all. They've been around forever. They are why I wanted to be in New York. I wanted to be in New York because I wanted to be part of a scene like the Abstract Expressionists like Irving was or the pop artists. . . like Andy. . .I thought this was really about a brain. I didn't really realize it was about money, and it really is just all about money. Art just reflects the culture; I don't see where it changes it. It's just a mirror of society and the viewer. People have taken that to such an extreme that everyone is just reflecting how rich people want to see themselves, and they do it really really well. A: Does anything do this in this culture if art doesn't do it? D: I might say that I don't know if anything does. But I can say that something like Glee is truly subversive. And here is why. When Reagan changed everything it started with the tax structure. He changed everything, particularly the burden of the tax structure, which moved from the wealthy to the shoulders of the middle class. It was the beginning of the end of us. In the Reagan years, the big television shows were Dynasty and Dallas, and these were shows about rich people. They were rich people looking fabulous, wearing diamonds, wearing dresses with shoulder pads, wearing their hair coiffed with big gowns. . . It was all about fabulous rich people. That was then, and there hasn't been a show where the underdog wins since before that time, since before Reagan. The reason Glee is so radical is because it is the first show in thirty years that champions the underdog. People have mentioned "Freaks and Geeks: when I've made this comment, but that was a cult show; Glee is one of the most downloaded shows on iTunes. This is the first show since the eighties where the underdogs are the heroes. That was the American narrative until Reagan. That was what every single Broadway show was; it was "Annie Get Your Gun" or "Funny Girl" or "Hairspray" (the movie). They're all the same. The fat girl gets the guy. The Jewish girl becomes a star. Annie Oakley becomes Annie Oakley. That is the immigrant story. That is what made America great. It wasn't a coincidence that immigrants wrote this music and wrote these shows. There is a reason they were all Jewish. They created that dream. It was the Hollywood dream, and it was the Broadway dream. It was the American dream. Jews made that dream. Neil Gabler wrote a book called : "An Empire of Their Own, How the Jews Invented Hollywood" that is basically the same premise. We are the people who provided America with this narrative. After Reagan, forget about it! It was like: "Winner takes all: America!" for the last thirty years. Along comes Glee and these terrible terrible times. No more social mobility. That immigrant dream, that’s gone. And all of these shows about talent that gets you social mobility, that's gone too. . .until Glee. And here is Glee, and it's huge. It's huge that it is Lea Michele and Barbra and Kurt, the gay kid, and the gay kids. It's HUGE. This is the most promising and hopeful thing I have seen, culturally, in almost thirty years. Yet it really isn't that subversive because it simply reflects a dream that people have. I'm obsessed with this show. I can't see it enough. I can't write about it enough. This show is big because it really indicates a cultural shift, just like Dynasty and Dallas were a cultural shift of enormous significance. A: History does seem to repeat itself. D: Well, I think that is the best we can hope for. We hope there will be a history. We hope we will go on. We hope it can repeat itself, but not with the corporations, the globalists, and the rich people in charge who are making sure things don't change. I'm sorry. They own the government. I'm not very hopeful, but at least the desire is there, and that is what that show is about.

D: Maybe if there was a second home option, but I am a New Yorker. You always come home here, to the city. In my heart I am really a country person with a big garden. But you know, where would I go? They would kill me. I'm a gay person; it is a limited option. I have considered L.A., but I am terrified of the earthquake. I think I could have lived there though, happily. Maybe because it's filled with New Yorkers. (laughing). But you know, I have to say, I was only there for 36 hours, but I was very impressed with Portland. I could not believe it; it was the only city in America that I've ever been in that felt like Paris in that everybody seemed adequately dressed, fed, having a decent time, and not overly anxious. I have never really seen that in a city in America before. Portland blew me away. I asked Denise (Mullen, president of OCAC) Why does everybody seem as if they are middle class here? I have never been in a city where I had that feeling. I slept a lot of those hours. Everything I saw was through the car window and at dinner, and that was it. I was blown away by the relative ease. It was like, who wouldn't live here? It was like the best of every single city. We (Pattie and I) are definitely coming back. A: How would you feel about the mass dispersion of your work? D: I would love it. As long I got paid, I would be happy. This is just the nature of images now versus another time. I want to make Yentl shower curtains. It would be genius. How beautiful would that be? Would you buy one? A: I would LOVE a Yentl shower curtain. Are there any current painters you think are making good work? D: I have been so busy, yet as for the things I have seen lately that have really stuck out in my mind Ken Noland's early work at Mitchell Inness and Nash last month was unbelievable. Elizabeth Murray's work from the seventies at Pace was unbelievable, but I live for that. A: I know you are so busy, but are you reading anything? D: Yes! Only because I got on the plane, and you're gonna laugh when you see this, but, . . .you know I really read a lot of political stuff, but this is genius. Usually I only read non fiction when I can read. But, THIS book is GENIUS. (Points to "Frank: The Voice"). My friend and the great painter Rochelle Feinstein just wrote a piece on boxing. She boxes, and we go to the fights together sometimes. And I had to tell her: Rochelle, you've got to read this book; it smells like the fights. And it does. It smells like the fights. A: Are you listening to any music? D: Yes, I just got Coltrane live at the Vanguard. It's like a four cd set. I listen to music all the time. I'm on shuffle now, permanent shuffle. This is the dinner party mix; here is typical set: Xanadu the musical, which is FABULOUS. Company, which is Sondheim. Monk's Dream, and Miles Davis. That is a completely typical mix. I save the Barbra for myself.

Posted by Amy Bernstein on May 24, 2011 at 6:37 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |