|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Kris Hargis' Me and You at Froelick Gallery  Hargis' All is Well Thirty-plus years ago, governmental social policies started to change and budget lines began to shrink for everything from inpatient and outpatient health care for veterans to arts programming. Religious organizations (in the case of welfare services) and charitable foundations were given the task of filling the gap. Even for wealthier trusts, this meant that dollars needed to be efficiently stretched. The outcome was that if arts organizations wanted funding, they had to meet new criteria. These criteria centered on attracting, or more precisely, serving a wider audience. A chamber quartet could no longer hope to get funding to simply bolster their budget for a series of concerts that only their well-to-do season ticket holders would enjoy. Instead, they had to develop educational programs and perform/inform in library atriums for busloads of school children. The same held for dance troupes and the like. At about the same time, we increasingly found tomes of information about exhibits appearing on art museum walls. An over-simplified timeline shows much attention has been given in the arts community to their new role, eventually taking the responsibility as credo. Art becomes a social contract, and the understanding and appreciation of art forms is made available to the public at large. All well and good, with the caveat that meaning and appreciation can be suggested but not directed. Re-consider the impresario, confronted with this new standard put upon his heretofore-insular world. Perhaps individual suffering or sacrifice means less, given the needs of others, and in order to continue in the au courant graces of audience and patronage, it may behoove one to give a nod of acknowledgement, or a sign that one is capable of compassion. It is this sign of humanity, not persistent cynicism that is to everyone’s benefit. In the process, the tortured creative soul discovers the self-portrait is not unlike the faces of those gazing back.

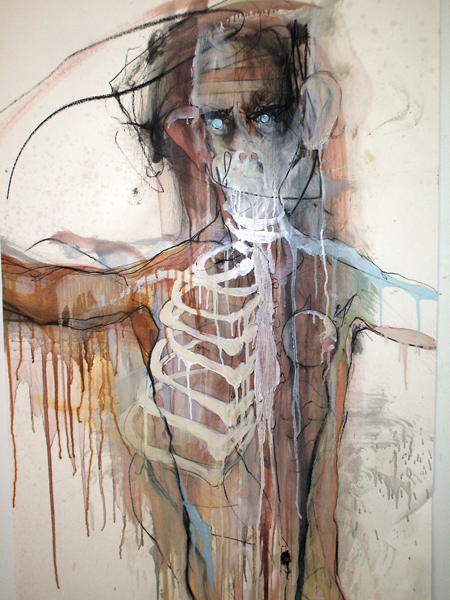

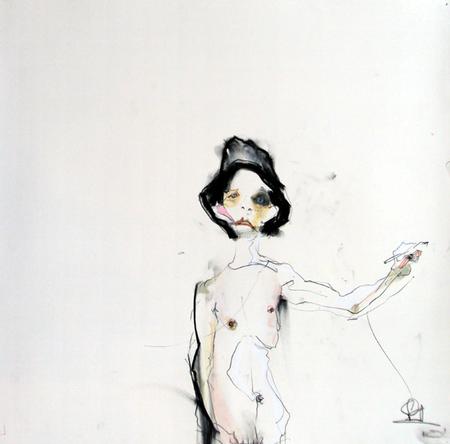

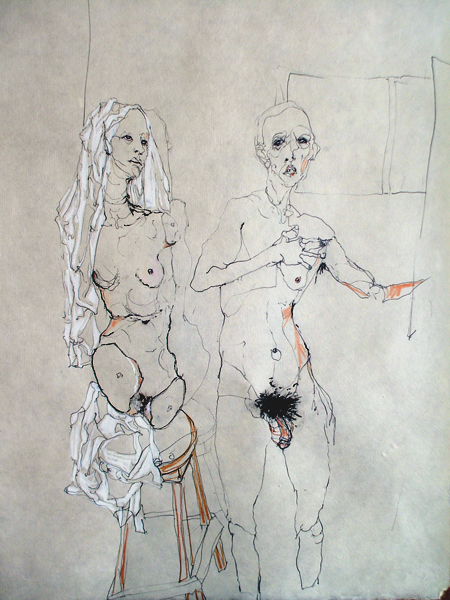

To The Hills Kris Hargis has begun this journey of discovery, or so the press release for his current show at Froelick would have us believe, “turn(ing) his attention to the trials faced by service members as they return from the battlefield to everyday life.” However, a qualification remains, for the very next sentence lists self-portraits as part of the exhibition. And so, we try to determine signs of his development from self-examination to the portrayal of another. In fact, titles and a saluting figure in “To the Hills” aside, there is very little in Hargis’ paintings that immediately suggests he has sought out the living casualties of war to document their suffering, unless it is a generalized personal pain that has haunted his paintings for years.  Me and You Horrors often beget detachment, yet there is no despondency evidenced in Hargis’ handling of media in his dynamic paintings; and here is where we may be more conciliatory toward the stated commentary behind this current work. In the piece from which the show is titled, “Me and You,” the artist extends his left hand to the edge of the paper to where the canvas awaits. His gaze is fixed on the viewer in a close study, while his right hand either fondles or covers his genitals at the bottom of the paper. He is aware of another’s presence and it is erotic. The Other is more present in “Us,” in which a male and female sit next to one another. Both are naked, yet the female form is without arms and legs, the bones exposed within the hacked-off thighs. Her pain has been caused, perhaps by an incomplete understanding, or even by contempt. The world with which Hargis begins to come to terms (me and you as opposed to you and me) is still young, molten.  Us Hargis has a signature style, one borne more from repetition of a technique than originality. The fluid, sometimes haphazard lines and pushed paint herald back to fifty years ago when everyone in a drawing class learned the 30-second life portrait and then called it art. That said, very little back then actually was quality work, nor was it developed with the same insight to the troubled soul that one finds with Hargis. You want grotesquerie and pain? Hargis’ subjects greet you with steely-eyes that could kill; others look away afraid, or, as in “All Is Well,” exhibit a numbed complacency. Hargis unflinchingly shows us a world where relief and redemption are hard to find. But noting the life-size formats of “To the Hills” and Remembered and Forgotten,” he is getting closer to others. Which necessitates a return to the press release: … a small bird grips a fragile branch which blooms around him; flowers wilt, captured in their last moments before dropping to the ground. Hargis, with simplicity and restraint, takes the viewer on a journey through dark and vulnerable places, and ultimately shows them to be a source of strength, beauty and cause for hope. Need for social relevance is generated from a lack, whether an injustice or the desire for inclusion and recognition. Hargis’ portraits are social only to the extent that they successfully emote the dark side of what it means to be human. (So grim are these paintings, we are satisfied with the withered flower arrangement and meet the finch with glee, glad to know that it may still be alive.) In this time of a growing art collective consciousness of sorts, Hargis still predominantly stands alone, but calls out, “This is me seeing the world. And, by and large, that world sucks.” There is no turning that view on its head to see the bright and shiny, unless, as Hargis has begun to realize, we can take comfort in knowing we’re in it together.

Remembered and Forgotten Hargis takes us into the darker places of human suffering. Yet, that darkness can also be less a place of fate’s pain than the unknown: the mysteries of life waiting to unfold; and one supposes, herein we might aspire toward some hope. Painting through to that place might be one way to go about it, and reinforcing that notion, Froelick has serendipitously given us another view on that bleak but sustaining pursuit in the work of Miles Cleveland Goodwin. His paintings are an alchemical mix of Odd Nerdrum meets Ingmar Bergman, and merit a tarry. Posted by Patrick Collier on March 10, 2011 at 9:17 | Comments (2) Comments hello patrick, kris hargis here. i came across your writing the other day and have read it countless times. i am a visual person, although compelling, i am not sure i am able to grasp everything you've written as you may not be able to grasp everything i've drawn. then again, maybe that is unimportant. regardless, if you have any interest in meeting up to discuss your review and my exhibition, let me know. this may not be the norm for you, as it is not for me as far as critiques go , but i feel obligated to represent my work to the dust! Posted by: kris hargis Kris, I'd be happy to meet with you. ptcpatrick at gmail.com Posted by: Patrick Collier Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)