|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Staring: An Interview with Catherine Opie Best known for her multiple series of portraits of lesbian, butch, and transgendered women, Catherine Opie is a remarkably versatile photographer with an eye for the powerfully personal and the formally sublime. Images from her series Girlfriends are currently up at the Portland Art Museum (through February 6, 2011). I caught up with her after her lecture at the museum to discuss identity, politics, historicity, and minimalist photography.

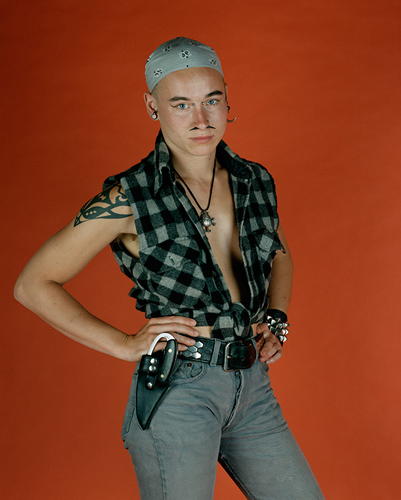

©Catherine Opie, "Jenny (Bed)," 2009, courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles md: Why did you return to your earlier portrait style with Girlfriends? CO: I wanted to make portraits in that style again and I wanted to photograph my friends and look at them again. I also wanted to mix up landscape in relationship to studio portraits. I was doing it in other bodies of work, like the high school football players and the surfers, but for this project I was really interested in placing women in the land. I wanted to explore the notion of visibility in a different way - we exist in space as well as in the studio - and I truly wanted to make a body of work on iconic butches and identity politics with that mix of portrait and landscape. md: In your lecture at the museum you mentioned that the solid color backgrounds from the early portraits were a nod to formalism and painting. Do you see the movement away from those backgrounds as a movement away from formalism in this body of work? CO: No, I still really like using formalist techniques, but you don't want to fall into too many comfortable tropes as an artist. You want to be able to experiment and move on past things. md: Being and Having, your early portraits, came out in 1995, right around the first culture wars. Now everybody is talking about the second wave of culture wars because of the Wojnarowicz controversy. How do you position yourself in that whole debate? CO: I'm in the show in the Smithsonian and I wrote a letter to the director to pull my work. But, like every artist who asked to have their work pulled in relationship to Wojnarowicz's work being removed, mine didn't get taken out of the museum. How do I position myself? As long as homophobia still exists, I will continue to make work in relationship to my life and visibility. But with Girlfriends, as with most of my work, I'm also really interested in the merger of the personal and political. The title Girlfriends is definitely a riff on Richard Prince's Girlfriends. But it also comes from the notion of butch identity today - many people in the butch community would prefer to use the male pronoun now, so it's my little fun riff with my butch buddies and myself. I'm saying, "you're my girlfriend" instead of my boyfriend. It's more a way to explore how contemporary thinking about gender and identity has usurped butch identity to identify more with masculinity. It's a play on gender. And some of them were my girlfriends, too. Some I've only coveted, but some have been my girlfriends. So there is much of my own personal desire within it, but a body of work can't only lie within one's own personal desire. Bodies of work are best when they can communicate on diverse levels of discourse. md: You talk a lot about gender identity and butch culture - how do you see your work in relationship to feminism? CO: It depends, what kind of feminism are we talking about? Radical separatism? Anti-pornography feminism? Within the notion of feminism, there's an enormous range of discourse. I am definitely a feminist in relationship to equal rights and empowerment - women need to be seen and heard, and we need to be represented. But I wouldn't say that my work deals directly with issues of feminism, except for the fact that I'm a very bold woman who's making work without making apologies about how I represent women. I'm not one of the Yale girl photographers - my women don't stare off blankly into space. They look at you. The history of the representation of women is about them being an empty vessel that you can place your desire on without them showing their own desire. They're not about confrontation. I wanted Being and Having to show women saying, I can be a butch dyke, and I can wear a mustache, and I can take you and have fun with you, but I can also be flipped over in a moment. It's about this play on female power. You see women so often being these vacant people staring off into space, and it drives me a little crazy after a while. md: You talk about your own personal desire in your work, and images share a lot of visual tropes with fetish and erotic photography, particularly the studio portraits. Do you see your work as crossing over in a Mapplethorpe-esque fashion? CO: I'm not interested in the fetish photographers, but Mapplethorpe was always important to me. He was who I could look at when I was in my early 20s. Not only did he model my own life in the leather community, he showed me that this mode of representation was possible. In the 80s I was really involved in queer culture, but I never made it my artwork. Then in the late 80s and early 90s I consciously made the erotic become part of my artwork, inspired in part by Mapplethorpe. md: In a lot of the portraits you're photographing your own social milieu. How does that affect the relationship between the photographer and the subject? CO: Some people I met just to take their pictures. For example, I had never hung out with Idexa before I made that portrait of her, and after I made that portrait she became my best friend. A lot of people just knew I was in town making images and asked to sit for me. Some of the subjects I already knew. My friends who knew me were harder to photograph. They were almost too familiar. And some people just don't really like being in front of the camera. Even though I saw something in them that I wanted to make a portrait of, they were awkward. The body of work is a total of over 60 portraits, including both friends and people who I just met taking their pictures. md: You've done some very powerful self portraits, but do you feel that there is also an element of autobiography in the portraits of your friends, since you're representing what was, in the 90s, not a well-known subculture that of which you yourself were a part? CO: There's a certain amount of autobiography there in relationship to how we recognize ourselves within other people. They become signifiers to a certain extent. Within that is a language of - ok, I'm cruising you, I know we can cruise each other because we're of the same milieu. That's how those portraits operate for me. They're not only representative of a community and culture that was being badly imaged and talked about, they're also an extended gaze and an extended proof. They're sexy photographs - they're hot. And there is a lot of seduction in play in relationship to how those images are constructed. md: In your lecture, you mentioned seduction as a way to open doors for viewers. Do you mean to the political content? CO: Yeah, I think so. You have to say, why do I keep wanting to look at this person when often I might confront them on the street and create negative meanings in relationship to how they're dressed or holding themselves or representing themselves. I might just think, oh, you're a freak. But all of a sudden with my portraits you can't enter them just as freaks. They're not Diane Arbus photographs, they're not freaks. They're these loving, beautiful, amazing people. I've watched people for years look at my work, and they're really engaged with it, they really look. And I think it's my belief in humanity, to a certain extent, that I can be a freak, but I can also operate not as a freak. And what does that title even mean? md: Since you made the first body of work, a lot of these "freaky" characteristics have become part of popular culture. Your work is very well known, very widely received. Do you think you might have played an ambassador role? CO: I think it's a really beautiful thing that I created a body of work that was so important for younger queers. Even if they were in high school, all of a sudden they came across something and felt like for a moment that it was safer for them to be who they are. So as an ambassador in relationship to that, I am so grateful that other people felt that they had a place that they could belong because there is work out there that does deal with representing them. I don't think that that was the intention when I was making the work, but I'm always amazed at how many people tell me how important I am to them because of the work that I've made. And that's very touching - it's a beautiful thing to do. But, there's a certain part of me that is so tired of fighting homophobia, that I do have a bit of cynicism in relationship to being a spokesperson. I don't think that somebody who's homophobic is going to look at my work and have an epiphany and decide that they're not homophobic anymore. But it's not really about that, it's about the fact that I'm still taking that space, and have the permission to take that space, and use aesthetics in relationship to that. md: You made a joke in your lecture about the "lesbian washing machine." Do you think some of your domestic photographs and erotic work are an attempt to normalize lesbian sexuality and romance? CO: I don't like the dichotomy of normal or abnormal. There's just humor in it, it's tongue in cheek. Yeah, we have cutting boards and we cut tomatoes, we have washing machines. It's to debunk this whole mythos of the homosexual pervert stalking your child. There are people out there who literally think we don't have the right to live, that we need therapy, that there's something wrong with us and that we shouldn't be having children and we shouldn't be having a desire to have families. So the still lives aren't about this notion of normalizing, but just saying, ok, come on. We are all here, we are all the same species, no matter what race or gender. There are these incredible fears and xenophobia that we have within our culture. Why do we have to come from such a fear-based perspective all the time? It's annoying. md: Moving away from your own work for a moment - you have some powerful ideas about identity, such as specificity and the way that identity is placed on groups of people, like you and your friends or the young football players. So I'm curious what you think about how identity formation, on the individual and cultural levels, has been affected by Facebook and other Internet communities, profiles, etc. CO: Social networking is fascinating. There are obvious concerns about real connections - who are your real friends. I don't have 2,000 close friends, but that's how many people are on my Facebook page. I'm curious to see where all of that goes in relationship to larger ideas around human connection. I have a 19 year old niece who has to check her Facebook page all the time. I ask her why, and she says, "or I don't know what's happening." What's happening in front of her isn't enough for her. So there are certain concerns in relationship to attention deficit disorder too, and what happens when there's no boredom or banality in life. Boredom and banality are really important for one's imagination. And waiting.  ©Catherine Opie, "Idexa," 1993, courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles md: Back to your work- you talked about monumental architecture referring to the freeways, and also the body as architecture. Can you elaborate on that idea, particularly in your portrayal of body modification? CO: We're borrowing from all these cultures with our style and our tattoos, just like architecture does. In the early 80s, our look was Levis and Convies or Doc Martens and a leather jacket, and we usually wore a cock ring on whatever side of our leather jacket we wanted to flag. Then Michael Jackson wore the leather jacket, he had the cock ring, and it was like - oh, that can't be a signifier anymore like it used to be in 1982 in the streets of San Francisco. So then we started modifying our bodies in relationship to our experimentation in SM culture. We were exploring what it meant to mark our bodies with cutting, piercing, scarification, branding, etc., and that became a signifier. You could look at somebody and see their tats and go, oh yeah, we're of the same tribe. Architecture does the same thing. It allows you to recognize different periods within culture. You go to Chicago and you're looking at stuff built in the 1930s, 40s, and 50s, and you recognize the era. I'm really interested in marking a time period with my friends, and creating a sense of history in relationship to body modification that also works on the tribal level of identifying with one another. And I think that's really incredible.  ©Catherine Opie, "Untitled #2 (Chicago)," 2004, courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles md: You do talk a lot about time and how you're interested in historicity in documentary photography, placing people in time. But you also talk about wandering, and refusing to mark a definite place for the viewer, such as in the mini mall photos in the American Cities series. So you like to place in time, but displace in space. Why? CO: I think that there often is displacement, but we believe that things should be so concrete. The way that history is written is ridiculous, because theories get dismantled over time. So why should I give such specific information beyond the date? We know the photograph was taken in 1995. Maybe that alone is enough because I want a sense of it being somewhat malleable. I don't have this relationship to the notion of truth or suspended believability, I'm more interested in this slippery area. So I had to do that on a metaphorical level, where the date is there but everything is untitled because I wanted the viewers to have the sense of freedom in relating to it. It doesn't have to be so much "I'm doing this because I need to document." md: So time gives you a way to root it, but lack of place gives it room for metaphor? CO: Yeah. md: You seem very interested in wandering and nomadism and temporary communities. Where does this interest come from, what is it about? CO: I've read a lot on urban design, and I enjoy doing the master planned communities and other bodies of work in relationship to the idea of the transformation of space. I'm really interested in that notion, especially from living in cities and watching how they transform and how a new identity can be formed within them over time. The transformation of New York from my starting to go to there in 1978 to what the city is now is unbelievably fascinating to me. And wandering is also interesting in terms of globalization. We're connecting with people from all over the world, but we still try to find this moment of recognition in each other, like "oh, we belong together because we have the same shared interests." People do it through religion, through creating a community garden - we as a species long for this kind of almost mirroring recognition. But at the same time, for myself, I'm more interested in this perspective of, yes, I know my tribe and I belong to a tribe, but I'm also profoundly curious about how other communities begin to form and what that means. My show coming up in Boston will feature photographs from the Tea Party, the inauguration, the immigration march, peace protests, the 100th anniversary of the Boy Scouts of America jamboree, and the 35th anniversary of the women's music festival. All of these exist within this contemporary landscape for me, in the same way that the football field becomes the site of American landscape. At this point I'm not interested in emptying out space like I did throughout the 90s, I'm more interested in this activation of space. What does it mean to activate, what does it mean to connect to this certain set of beliefs. Honestly, I don't know what the new work really means at this point because I haven't sat with it long enough to talk about it. But there's something in relationship to creating images of this time, of these culminations of groups of people that's just really fascinating for me. Maybe it's just because I'm bloody curious and I stare, so I go around and I just make this stuff. md: You linked your 1999 and In and Around Home series to crises, specifically Y2K and the post-9/11 fear of terrorism. Do you see this new body of work as responding to something happening now, like the economic crisis? CO: I think American Cities, to a certain point, begins to reflect on the economic history of this country. But no, while I'm not apolitical - I'm a very political person - I don't want to make work that is necessarily telling people you should believe in this or that. Except, of course, not to be homophobic. This new work kind of started off with my interest in American genre painting. I was really fascinated with this notion that in American genre painting a narrative was formed about a period of time. So the photographs are also creating this narrative of how divided we are as a country. It's not telling anybody how to think, but it's merely recognizing all of the different factions that are at play. md: You mentioned that you think that artists should work in dialogue with each other as well as society. Is there any artist or body of work that you feel compelled to respond to right now? CO: No. But I would say that it's very hard to go back to being a street photographer because photography is operating in this place of new abstraction and love of analogue. So in a certain way I'm responding to the fact that contemporary photography is so disinterested in the documentation of the real. I've just plunged ahead and done things even more overtly like a photojournalist. They're not photojournalism - a newspaper would never print these photographs - but there's a little bit of a response to what's happening in relationship to photography's place in contemporary art. However, the work also in response to the significance and importance for us to literally bear witness. And in doing that archives are created and out of archives come a significant record of our time at the moment. And I am interested in how photography can work in that way.  ©Catherine Opie, "Untitled #11 (Icehouses)," 2001, courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles md: Of course, you previously spent a while breaking away from truly documentary photography, exploring a way to make minimalist photography with documentary elements. Was that purely a formal exercise? How do you approach this idea of minimalist photography? CO: There's a certain kind of minimalism that happens in bodies of work like the Surfers and Icehouses, and I'm interested in this minimalism in relationship to painting. How a photograph can also do that, but still be a source of representation - you can look at this big blizzard, but still say, oh there's a little icehouse. So minimalism doesn't really happen in the portraits or other bodies of work for me, it's just in relationship to what I'm trying to do with landscapes on a conceptual level. The use of minimalism is in response to how we look at images and what they relate to cognitively. All these collectors come up to me and say, "I love your paintings." Of course, they're photographs, but for them, in their minds, they operate as paintings. I'm not trying to make photographic paintings, but I am interested in how people often end up reading my work that way. And it's hard to make a photographic body of work that does begin to inform a bit of minimalism while still truly being just a document. People have tried to do it by photographing clouds, etc., and they end up going to the cliché. I'm interested in the cliché a little bit, but my work is more about the idea of the sublime and the suspension of belief. Posted by Megan Driscoll on February 03, 2011 at 19:53 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |