|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Jay Steensma at Pulliam Gallery

There are degrees of "have-to" when it comes to making art, perhaps regulated by a self-consciousness that all artists have in various manifestations. It is somewhere on this continuum that distinctions are made regarding who is the outsider, the hack, the naif, the fine artist, or the Sunday painter. All are false as generalities, as a sum total of mitigating factors are often compromised in order to categorize. Even so, what criteria must be met to call someone an outsider artist? Is the status retroactive, meaning should one have any formal art training at all, can the given circumstances of one’s life nullify that training and accumulated knowledge of art history? Does a pattern of socially alienating behavior achieve the same effect? How does one market a long-deceased, University of Washington trained devotee of the Northwest School who was also bipolar? With muted colors and sparse composition, or a lack of pretense with a corresponding economy, in a way, Steensma embodies the spirit of the region and his time; nor can I imagine a more rugged individualism than that found in mental illness. But this latter sentiment is borne out of romanticism, similar to the notion that madness is in someway divine. Never mind the pain and isolation it engenders. That is not to say the mad artists — geniuses or otherwise — are not out there, as artist Jean Dubuffet's Musée de l'Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland indicates. According to Dubuffet, the extreme alienation of mental illness is the domain of the pure artist, and the culture-at-large are the swine who wouldn’t recognize the pearl if it hit them in the face. The discomfort goes unrecognizable for the sedate cultural consumer who readily nullifies the imbalance of any extreme passions imposed upon them by focusing on the lines and colors and, ultimately, a consensus. On the other hand, to think there is a greater percentage of undiscovered mad masters than artists who shop for groceries at WinCo may be wishful thinking; yet, both types might be just as alienated from the Inner Circle. What is rare, despite the mythos surrounding the genius of insanity is someone who thusly disabled and still manages to pursue a constructive outlet as well as be given the time of day. More often than not, it takes a village for recognition.

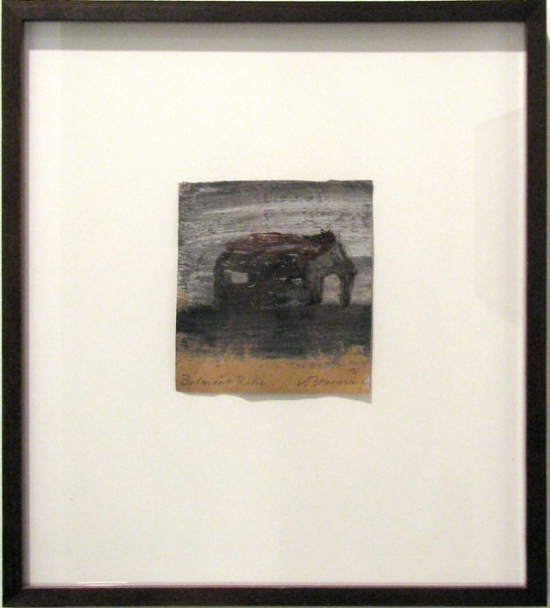

I knew nothing of Steensma or his work when I saw his "Bird of Prey (Wartime)" at Pulliam a couple months ago. Yes, it has the tropes of crude media that one is accustomed to seeing in a lot of outsider work; yet there is a dynamic quality to his mark-making that to my mind put the work on par with a legion of action painters from the second half of the last century. Still, a body of work may not be as inspiring as one particular piece, yet that one outstanding is what may pull the viewer to more carefully consider the larger body of work. There are three general observations that can be made from Steensma's paintings at Pulliam: The bird and fish paintings portray the animals on the same aspect, head to the left; the cottage paintings depict the same building, squat with one window and a door; in general, Steensma appears to favor a limited subject matter. We are thereby forced to consider content, which seems just as important to Steensma, if not more so, than the act of painting. It may not be out of line to suggest that Steensma is working with and through some totemic issues, the repetition making the strongest case for such speculation. A reason beyond an affinity for birds and fish, the repetition of these particular motifs eludes me, The houses are another matter. Wesley Wehr, in his memoir, "The Accidental Collector: Art, Fossils and Friendships" (2004, University of Washington Press), writes that Steensma returned to Seattle after a stay in Belmont, Washington. It is also known that Steensma was born in Idaho. One of his house pieces in the current exhibit is titled "Idaho," and Pulliam's website shows two more house pieces entitled, "Belmont" (1994) and another, "Belmont Relic" (1991). Steensma seems to be painting stand-ins for memories.

Make that four observations, or rather, another aspect of the same repetitive nature: the use of the word "relic". Awash in memories, perhaps fond of simpler, purer times, "relic" not only refers to something old, but also the remains of saints. Much of Steensma’s work that is not represented in the Pulliam exhibit is of religious reliquary, which brings me to observation number five: the letters/word "ECO" in many of his paintings. Given the time period, primarily between 1990 and 1994, it is doubtful that they have the same meaning as they carry today, namely, being short for 'ecology.' Given the religious subject matter that enters into the work, it may be more likely these letters represent 'ecce' or a shortened 'ecce homo', the suffering Christ crowned with thorns. To Steensma's credit, the desire to make these types of inferences draws one closer to his work, and perhaps his world.

Ultimately, one gets the feeling that Steensma, known for knocking out these works by the thousands, while working on one piece, is already anticipating the next. The work is not so much considered as driven. Either that, or with a new-found audience for his work, production was incumbent, even affording a shift from working on paper bags to stretched canvas and Arches paper. (The inventory of Wehr's papers at the University of Washington library lists over 200 of Steensma works in the collection, 95% of them from 1990 and later.) It is hard to determine which is the most prominent aspect of Steensma's career: the return of an artist after a long and debilitating fight with mental illness, the sheer volume of the work he made in the final ten years of his life; or, the establishment of a market for the work. After all, the repetitious nature of Steensma's work might not play so well if he were an artist not known to suffer with a psychosis. In his context, Steensma's totems function as sort of a purifying mantra, a meditation to empty an obsession. Most likely, it is a combination of these factors that provide a human-interest story that captures our imaginations more than the nearly obsessive repetitious nature of his work. This is not to say that Steensma art lacks merit. As rough-hewn as it may be, the dynamic quality of much of the work parallels the obvious enthusiasm with which it is made. These factors are what have made Steensma a deserved staple of several Northwest galleries; yet, the familiarity that comes with the multiple venues may give audiences an assurance that the work is collectible while at the same time distancing them from this artist's plight.

Posted by Patrick Collier on February 25, 2011 at 1:59 | Comments (1) Comments Well, Patrick, you bring up many new thoughts for me. At any rate, I like the Steensma samples. Posted by: james curran Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)