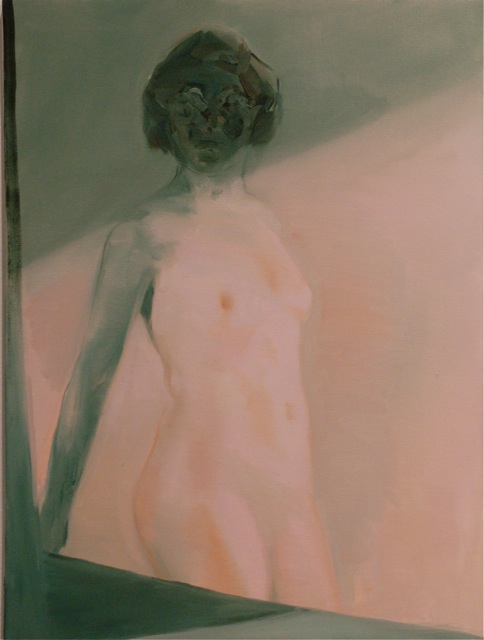

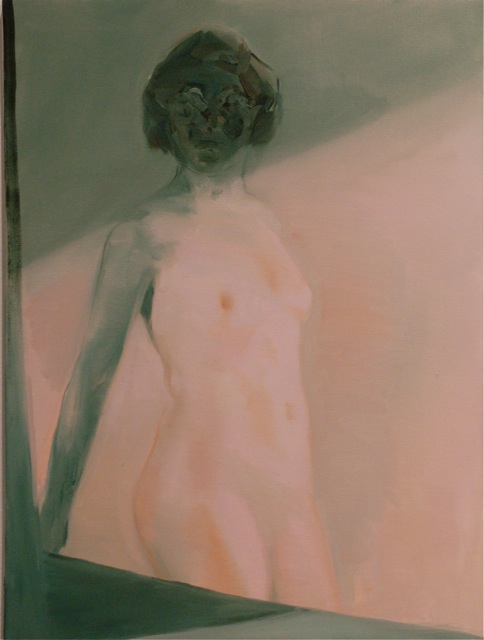

"To Conjure You Up and Make You Fade" 2009, Kaye Donachie

"Between My Head and My Hand There is Always the Face of Death" is the title of Kristan Kennedy's latest curatorial foray at PNCA's Feldman Gallery. An appropriated quote from the late artist Francis Picabia, the quote hints at the existential nature of the exhibition, encompassed by the continuation of the unbelievably long and rich history of figurative painting. This history, exhausted and revived interminably, mimics the heady content of the exhibition pointedly, subversively and subtly emphasizing and referencing its own fragile mortality, as well as ours. It is a refreshing delight to see such good painting, even on a small scale, and even when it is good, old fashioned, quirky, bad painting, and I encourage Portlanders to spend some time with these works; they are uncharacteristic of anything shown here.

The depiction of the human body is always a portrait somehow, as the head of said body and respective contents are of course implied and understood. Norbert Schwontkowski's "Schirm" 2006 is a pillar in the group of this exhibition's understated triumphs. Schwontkowski is amazing at making one's existence somewhat humorous while coincidentally granting it the weight of its self reflective consideration: in essence human frailty pictorally summarized and rendered. In considering this frailty, our brains are at once endearingly meek and infinitely unfathomable, and Schwontkowski's paintings lay this assertion bare. His pictures are eloquent and shattering and funny. The composition of this piece directs the viewer brilliantly, as we consider two bare legs and feet, one in shadow, one in sun, and the vastness of the sea and beyond in the distance. The micro and macro nature of our thinking are pinpointed in this little painting of bare feet on the beach, the big and little pictures of toes and sea.

"Schirm", 2006, Norbert Schwontkowski

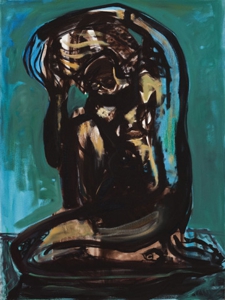

Amy Bessone's works in this show echo back and forth throughout the canyon and canons of bad painting (interesting as Picabia was considered as a 'bad painter') and art historical reference. Bessone is apparently a very good painter, by the line quality and stand alone, resplendent, visual power of these works, and thus the choice of their rawness is purposeful, yet mysterious. They recall a plethora of art historical references, i.e. Matisse, Gauguin, Picasso, and various icons of German-Expressionism, yet they seem somewhat one linery, particularly the "Sensuous Studies".

"Sensuous Study (Nude with Ochre)", 2009, Amy Bessone

The fact that Bessone is a woman subverts these subjects that are usually portrayed as objects somewhat, sort of. This seems to give them some sort of power, yet it is not entirely convincing.

Elena Pankova's playful bunch of paintings marry the relevance and relationship between abstraction and figuration bluntly. All of the works in this exhibition do this by the sheer, staked presence of the paint as representational bodies, yet Pankova's paintings create this relationship with the least number of stops in between. In viewing these paintings, the colored bits of facial references surface and dissolve as functioning sign and pure abstraction, and both experiences are lovely. Pankova's compositions aid in this effect, the edges of the canvas pushing the notion of its objectness as surface and its illusionistic symbol as body. The notion of the inanimate foils the living, and humor mingles in between, as requisite for our survival. Pankova's humor allows her nod to constructivism to be both accessible and self deprecating, a trait she shares with Schwontkowski. The house plant hung among the paintings seems also like her way to humorously draw our vision out into the world to re-examine our own ridiculousness again with both a real world and picture plane perspective; the shape and nature of a houseplant could not be more mortal or finite. Thus, Pankova reminds us not to take ourselves too seriously.

Elena Pankova, Installation View, 2011, Feldman Gallery

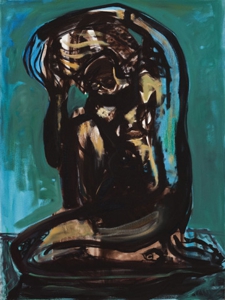

The nature of this exhibition is infinitely self reflexive and not, relying on a tongue-in-cheek depiction of the body as existential vessel and concrete reckoner. Kaye Donachie's paintings are the only pieces in the show that do not rely on a level of the absurd, instead taking up the torch of heartfelt nostalgia and longing inherent in the body of a loved one. Donachie's paintings are not ironic or kitschy, and the muted tones of the oil paint respect the soft folds and nuance of muscle and bone beneath skin.

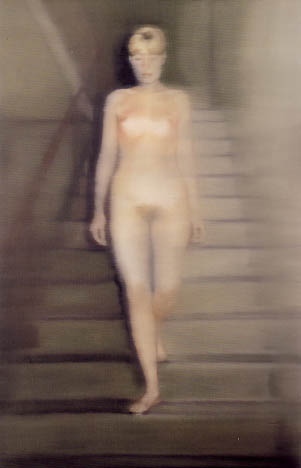

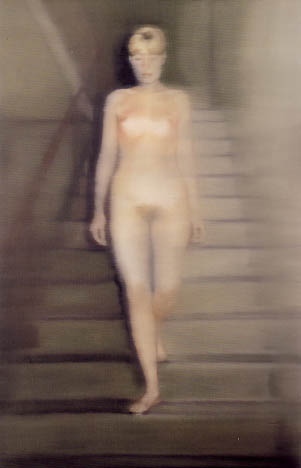

These glowing forms insinuate loss and death, their light reminiscent of old photographs and thus memory. Gerhard Richter's "Ema (Nude On a Staircase)" comes to mind.

"Ema, (Nude On a Staircase)", 1966, Gerhard Richter

Our flesh is not the earthly reminder here that it is in the other works, but the ethereal currency of love and loss, as precious and as ungraspable as light itself. While Donachie's compositions occasionally may appear to border on the naive, the paint handling and subtlety of purpose yield to a more contemporary romanticism. These works complete the literal and figurative frame of the body of the exhibition, as playful humor meets the dark well of loss and the questions and descriptions of the human condition skirt between them like flies.

"Between My Head and My Hand There is Always the Face of Death" will be on view at PNCA's Feldman Gallery until March 26th. Kristan Kennedy, the exhibition's curator, will be speaking at the Portland Art Museum on February 10th. Kennedy will also lead a walkthrough at the Gallery on February 15th.

And, on February 15th, Kristan will also lead a free, public walk-through of the exhibit at PNCA. http://www.pica.org/programs/detail.aspx?eventid=696

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)