|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

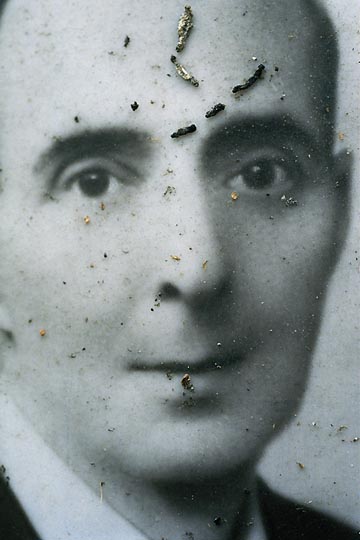

Torben Eskerod at Blue Sky Gallery  install view As we get older, the photographs of family members kept in albums increasingly become mementos of the dearly departed. For a matriarch or patriarch of the family, a particularly memorable or essential image may get installed into the face of a tombstone. Doing so maintains the semblance of the living relationship. Yet, stories passed from one generation to the next are not enough to keep that image sharp and new copies do not replace the worn and weathered when the time comes for one’s own photo to be placed in granite. A somber reminder that life goes on, and those not thusly engaged eventually become anonymous except, perhaps, for the family name. Torben Eskerod’s exhibit at Blue Sky Gallery is comprised of a collection of these photographs, re-photographed and displayed as large format prints. The fact that the originals were taken at Campo Verano cemetery in Rome is irrelevant, for there are no names attached to the images, and the images are portraits absent of a background. They could be any Caucasians, anywhere. The deterioration of the photos behind their glass encasements tells us that we are looking at dead people. There is an element of nostalgia that lends a certain and perhaps desired effect, but is lessened by the anonymity, and so family members who have passed will be put aside from the discussion in order to concentrate on other associations that begin to circulate in one’s mind, those of Christian Boltanski, Roland Barthes, and Charles Baudelaire.  Christian Boltanski  Torben Eskerod Boltanski brackets the photographs of anonymous victims of the Holocaust as a way of remembering. Eskerod categorizes his subjects into formal arrangements based on the photos’ defects or gender. Boltanski has a more specific agenda; Eskerod’s is more open. Both men present these photos for what they are, objects imbued with the sensibility of the artist. They are, after all, found objects recontextualized into categories, and in that process, engage in a sort of violence to the portraits: people placed into subgroups based not upon any discernible biography (aside from they are dead, and in Eskerod’s case, within the same cemetery). Shared history is not something for which we ask. Commonality is for the present, perhaps the future. Aside from a vague notion/desire of an afterlife, we typically do not die in order to join others in solidarity as victims of war, disease, old age or at our own hand. It is not an experience, this ending of experience, that one can readily relate as the dead have little agency.

Roland Barthes writes that the photo, even a photo of the living, is an effigy, a ghost. Taken individually, one can still imagine the “soul” of the person behind the grave marker; however, the groupings move away from empathy. Formal considerations become bureaucratic, and hence a caveat: rules, associative or of a consensus, deaden. Yet, even a photograph taken when alive seizes that person still living and breathing into a stasis. There is an understanding that this small death is not serious, and passes as “that was me then” but I am still here, new, as it were, changing, and in that I have changed, I have escaped that death. For the tombstone, all is static: an intentional gesture, namely, having a photo chosen, is how we are will look for those who never knew us. The subject in the photo has no say in the matter and passersby have their way with the presentation of a self gone. As the photos disintegrate, they take on new form thereby moving further away from a personage and closer to a mere aesthetic.

It is mildly ironic that Eskerod’s photos once again cease the aging process. That said, some of the pictures manage to tell a story, or rather extend their meaning beyond the portrait. Individually, there is a not-so-terrible beauty to be found, and in some, a certain poetry. The strongest example might be the image of a man whose photo has managed to remain well-preserved, despite the fact that at least two generations of larvae have hatched behind the glass. The forms disappeared and were no more than a dream, A sketch that slowly falls Upon the forgotten canvas, that the artist Completes from memory alone. Then, O my beauty! say to the worms who will Devour you with kisses, That I have kept the form and the divine essence Of my decomposed love! — Charles Baudelaire, from A Carcass in Les Fleurs du Mal In many instances, a photograph of a photograph can be considered cliché and banal. However, in the strictest sense, Eskerod’s photos are encasements that contain photographs, and therefore can dodge such an assessment. In much the same way, the formal categorization of the images dances with the trap of sentimentality, but the strategy — perhaps the only solution available — is more akin to formalist curatorial strategies and therefore softens the impact of any statement on fragility of life. Even so, given the subject matter of this exhibition, if there is one notion that persists for the viewer, it is a re-found reverence for these dead strangers, and Eskerod has admirably managed that sensibility. Posted by Patrick Collier on December 10, 2010 at 11:48 | Comments (4) Comments Curious about this thought from your review above: "The fact that the originals were taken at Campo Verano cemetery in Rome is irrelevant, for there are no names attached to the images, and the images are portraits absent of a background. They could be any Caucasians, anywhere." If the artist titles a piece that provides information, isn't it relevant? Maybe it wasn't relevant to your viewing of the work, and maybe the faces, to you, could have been, "any Caucasions anywhere," but, as the person reviewing this work it sounds as though you ignored the titles, and perhaps the statement? You go on to say, "...people placed into subgroups based not upon any discernible biography (aside from they are dead, and in Eskerod’s case, within the same cemetery)." Once again, I am sort of amazed that you seem to take lightly the community of people that has gathered in this gallery. Isn't it even slightly interesting to you that the people are all buried in a cemetery on the other side of the world, and you are now standing in a sort of virtual/visual cemetery of theirs? Of course they didn't all live together, but they lay in death together. And, this is irrelevant? I don't know Torben Eskerod, and I haven't seen the show. So, I can't comment on the work. But, in attempting to read your thoughts to try to understand this show, I have to say I might be more confused than if I had just seen pictures and titles. When you add thoughts to art, the idea is to communicate that you have an understanding that is helping my understanding of the show. I don't think you understood this work. Lastly, in your final thought you claim the following: "In many instances, a photograph of a photograph can be considered cliché and banal. However, in the strictest sense, Eskerod’s photos are encasements that contain photographs, and therefore can dodge such an assessment." So, am I led to believe, as a hypothetical, aspiring photographer, that if I simply take photos of photos and place them in encasements that they'll then dodge all assessment as clche or banal? This could be the funniest thing I have seen in an arts writing piece, maybe ever. For that, I thank you. Posted by: symplvision Thank you SWI Posted by: Stephan P. Ferreira SWI... well it made perfect sense to me but I've actually seen the show, so I don't have your handicap. Seems like you are missing the heuristics at work here. Death has an anonymizing effect and for me Patrick's take captured the sense of walking into the gallery. All of the photos are untitled by the way... so titles don't give us any more information here and Eskerod's decision to not title them certainly conveys his ambivalence for those specifics leading to Patrick's sense that knowing that information is irrelevant. There is a fascination here with mute images engaged by strangers without much info and it does play extremely well with Baudeliare's ennui. The name of the cemetery certainly didn't change the way I experienced the installation at all. As for your hypothetical use of photos in encasements that is a reductio ad absurdum. It's pretty clear Patrick felt Eskerod pulled off what in most people's hands would be cliched. For example, I'm certain if I described how Picasso fractured the human figure to you and you followed those simple instructions your results would not be as successful as Big P's. ???? Overall I believe it is the sense of muted ennui executed with such a deft touch (which Patrick describes) that makes the show notable. Lastly, if that's the funniest thing you've ever read in arts writing... you haven't been looking terribly hard. I hope you have a chance to see the show, it isn't funny at all though.

Posted by: Double J your thought seems to stand on the assumption that, "Death has an anonymizing effect..." and perhaps this is the same perspective as Pat Collier's, but I'd argue that just the opposite is true. Death has a unifying effect. There is empathy in viewing art, and these passed/past/present souls are now, instead, the once anonymous dead souls, now exposed with a story to tell. to ignore this is to ignore the narrative of the show. JJ, you don't have be in that space to know that, and to ignore that is to ignore the obvious story. (At least, that's the obvious story I see when I see a bunch of dead people pictured largely in one room.) Also, your Picasso analogy is a bit disproportionate. (According to my calculator anyway.) As for most arts writing, it's true, I usually try to ignore it. Or, are we reduced to exchanging hyperbole now? Posted by: symplvision Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)