|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

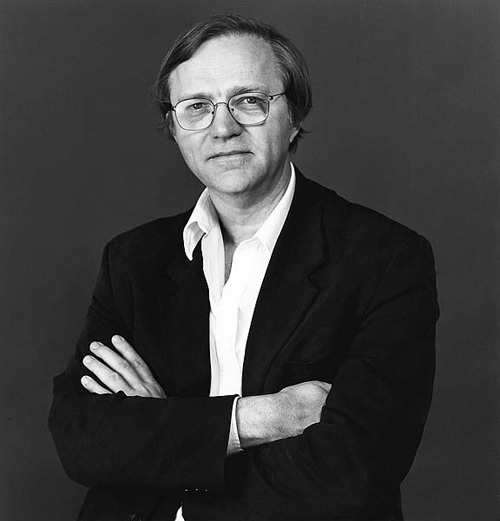

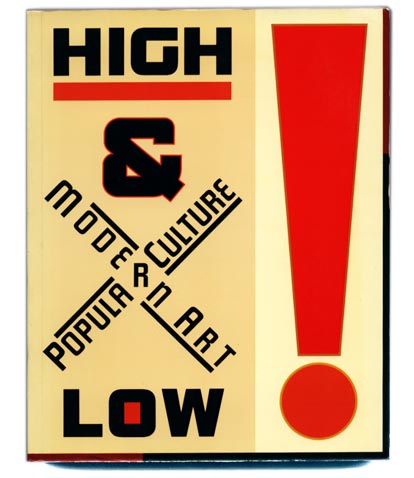

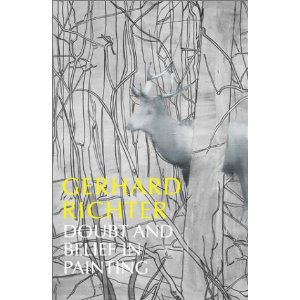

Interlocution: an interview with Robert Storr  Robert Storr is one of today's most eminent curators as well as an artist and arguably a philosopher. Currently he is dean of the Yale School of Art. He was the artistic director of the 2007 Venice Biennale and Curator of the Department of Painting and Sculpture at MoMA for over a decade. I had the opportunity to listen to him lecture this April at the Donald Judd conference "Invenit non fecit." I spoke with him after the conference and he agreed to this interview. Q. Kirk Varnedoe has had a huge influence on many, how has his example influenced you and your work? A. Those most influenced by Kirk were his students, and beyond that people who worked under his direct supervision on the various exhibitions he organized. Frequently his assistants were former students as was the case with Pepe Karmel and Ann Umland, as well as with Adam Gopnik with whom he shared curatorial credit on, "High & Low: Modern Art and Popular Culture," his inaugural show as Chief Curator of Painting and Sculpture at MoMA. I was never a student of his – indeed, except for a handful of courses at Swarthmore where I received a BA in French and History and at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago where I received a MFA in painting, I never had any formal academic training in art history. What I know I learned from reading on my own, from talking to artists and above all from looking hard at many things over many years. The high esteem in which Kirk's students, assistants and collaborators hold him is something I have witnessed repeatedly, and so too his generosity towards them, which explains it in part, his drive to rethink art history as it had been taught in universities since the 1950s and 1960s accounts for much of the rest. Nor did Kirk and I ever do a show together though I contributed some texts to his "High & Low" and Pollock readers and he contributed one to my Chuck Close exhibition catalog.  Kirk Varnedoe: High and Low, 1990 The truth is that when Kirk and I really met for the first time during the year before "High & Low" opened, I had laid out and started to cut my own path through the thickets of established ideas, modernist as well as post modernist. I suppose that's why Kirk was interested in me. To the extent that his trajectory intersected mine we had much in common. To the extent that they diverged we had much to discuss. But we bonded over the fact that neither of us was prepared to accept at face value the dogmas we had run up against, and neither of us wanted to replace them with new dogmas. Instead we shared the hope of clearing away received opinion with the aim of getting a better, less ideologically entangled view of a wider array of modern and contemporary art. So I can honestly say that Kirk didn't influence me but that he was the best of interlocutors, and the most fair-minded of professional colleagues. But Kirk did change my life; based almost entirely on a hunch since I had never before worked in a museum, he gave me access to the greatest collection of art one could dream of, and gave me free rein to make exhibitions from it as well as a free hand in conceiving of and organizing thematic and monographic shows. Without his having taken that leap of faith, and just as importantly, without his having backed me up when others doubted his wisdom, I would never have been a curator or a museum person of any kind. I tried my best to show my gratitude by backing him up when he was under attack outside and especially inside the museum. I did that not simply to repay a debt, but out of deep respect and liking for the man who was in so many respects different from me. Q. How is the role of the art critic evolving in the information age? A. Between scholastic wool spinning and career driven opportunism in the academy on the one hand, and flat out corruption by the power of money and publicity in the commercial sector on the other, criticism is at its lowest ebb in memory. If you are not willing to bite the hand that feeds in the Education Industry or the Culture Industry you can't write truthfully about art and its context. Yet the most unreliable writers are those who pretend to stand wholly above or apart from these structures – the Faux Flaneurs of the glossy magazines, and the Fake Outlaws of the Gonzo art press. The problem is to admit to being enmeshed in one or another part of the "system" and at the same time speak frankly about what one sees and understands despite being in such a compromised situation. That is the essence of Baudelaire's first critical text "To The Bourgeois" in which he exposes all the contractions of his position as partial rather than impartial observers and all the hypocrisy of the public ostensibly "disinterested" engagement with aesthetic idealism. The Information Age changes very little in that equation; it simply multiplies the number of venues in which sloppy or dishonest thinking/opinion-making occurs and fatally incomplete or false "information" about art is disseminated. As Felix Gonzalez-Torres accurately said; we do not suffer from too much information but from too little meaning. Good critics distill art's meanings; in part by choosing carefully what they write about, in part by writing carefully about what they choose. Q. Should museums be trying so hard to fit into the information age's popularity contest driven strategies, for example the Guggenheim's YouTube show? A. Winning popularity contests is for people trying to get more pictures in their junior high school year books. Getting into group shows at museums and alternative spaces where the group numbers more than thirty and the only thing that unites them is the desperate need to be shown and the desperate need of curators to hedge their bets is like being in the junior high school follies. Nobody wins at that game.  Alfred H. Barr Jr.: Cubism and Abstract Art, 1936 Q. Does Alfred H. Barr Jr. have an influence on the way curators present art today? A. Barr is a far more complex and progressive figure than the image his old line admirers and recent critics would have us believe. And his example is far more useful for curators to think about than that of virtually anybody other than Harald Szeeman. Both men represent problematic models because both men thought big and acted boldly which almost guarantees that there are issues they glossed over, things they missed, expediencies they took. But Barr and Szeeman and a few others - Sandberg in Holland, Bozo in France - had real vision, insatiable curiosity and catholic taste. There is lots of high flying talk these days but few very few curators or critics with a vision large or small that lives up to their rhetoric. Q. Can you give a definition of what art is for you? A. Following Rauschenberg's dictum I would say that art is what artists say it is, and the fact that they say contrary things means that its definition and the values it embodies are always contested. The arguments over what modern art is or was represents the content of modern art; looking at the things that are in the galleries at MoMA implies listening for the murmur of debate that envelopes each object and binds each dialectically to every other object. There are no right answers and no final judgments; just more or less articulate, open-ended and fruitful ones. Q. Would you say that the overwhelming amount of information is leading to a technological nihilism? How is that playing a role in the DIY and Social Practices movements? A. Technology isn't a threat to art; stupidity, credulity, lack of imagination, lack of appetite and mental inflexibility are. Nihilism isn't a threat either, and neither is critical cynicism; on that score ideology and doctrinal purity are the greater danger. Q. Art schools are producing more artists than they were 20 years ago. Is the university art world bound for a crash? A. A market crash? An unsustainable academic economy. Perhaps. But my concern is with what goes on in schools and so long as students understand that they are there to learn and to question and to make things for which there is not a priori necessity, and that their choosing to be an artist does not mean that the world owes them a career or that they are entitled to special status with respect to others whose lives are devoted to different activities, then art schools are as good a place as any, and better than most for a person to come into their own and form an unalienated working relation to their own faculties and capacities. All my life I have worked too hard at various job to pay for the freedom to paint and draw. Painting and drawing have never paid for themselves. I have no complaints and do not feel badly done to. Q. What is theory’s relationship to art? A. Theory is a challenge to think more broadly, more critically and more supply. Thinking well is good for art. That said, theory is no substitute for visual or manual thinking, and no protection against bad work and no excuse for doing it. Q. What is the most important topic art is addressing today? A. How to see the world afresh. Q. Is the art world lost or will a more specific direction appear in its current? A. There isn't just one art world—there are many. Some are lost. Others know where they are and what they are about. The problem is whether the individual can tell the difference, whether they have the courage to choose the right milieu and whether they have something to contribute to art communities that are productive, self-critical and active regardless of specific rewards and the approval of outside authorities. Q. What is more important to preserve: the experience or the aura? And how does this affect interactive art as it ages? A. Aura is experience. As Benjamin defines it, aura is not some metaphysical nimbus surrounding the aesthetic, it is the uniqueness of each encounter between a specific viewer and specific work in a specific time and place. Memory of experience preserves aura to the extent that anything can, but the only real guarantee is re-experience combined with a recognition of how distinct each encounter with a work is from the ones that preceded it.  Robert Storr: Gerhard Richter: Doubt and Belief in Painting, 2003 Q. Does it apply differently for Judd, Richter and Robert Gober's works? How about Jason Rhoades or Martin Kippenberger? A. Yes, but the difference of intensity depends more on the viewer than the artist – is more about what the viewers bring to the occasion than what the object provides – at least after one passes a certain threshold of artistic merit. Q. Can you send me a picture of your most prized work of art? A. No. Q. What is the one book or essay that you have written that you would want people to read the most? A. I would have to make a montage of fragments from many and trust that the reader would fill in the blanks according to the tension among the various, apparently contradictory statements I'd selected. Q. Are you the last of the scholarly curator/art historians (it seems like curators have become increasingly more like showmen)? A. No. But I don't think being a showman is antithetical to scholarship. Great lecturers like great exhibition-makers are showmen to the benefit of the ideas they espouse, the work they advocate, and the audience they hope to reach. By all accounts, Meyer Schapiro was an extraordinary lecturer. Vincent Scully is famously eloquent. Kirk certainly had great panache when he spoke. In an entirely different manner so did Harry Szeeman, and he was the showman's showman when it came to mounting exhibitions. I don't see the world in dichotomous terms, and given that all of us have strengths and weakness I nevertheless believe that over the course of our lives we should test all options, try all possibilities in order that the art we believe in has the best chance of being considered from every imaginable angle and we strive to the best of our ability to see that from every angle it amaze others as it has amazed us. Robert thank you for your words. Posted by Alex Rauch on November 05, 2010 at 12:11 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |