|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Interview with Alison Saar Alison Saar is a well known and sometimes controversial sculptor who recently

completed a

commission at Lewis and Clark College campus called York: Terra Incognita. She also has a career spanning exhibition titled,Bound

For Glory,

at the nearby Hoffman Gallery and runs through December 12th. To discuss

her work, PORT sent Gabe Flores to talk with Saar and learn more about how she

mixes life, art and history.

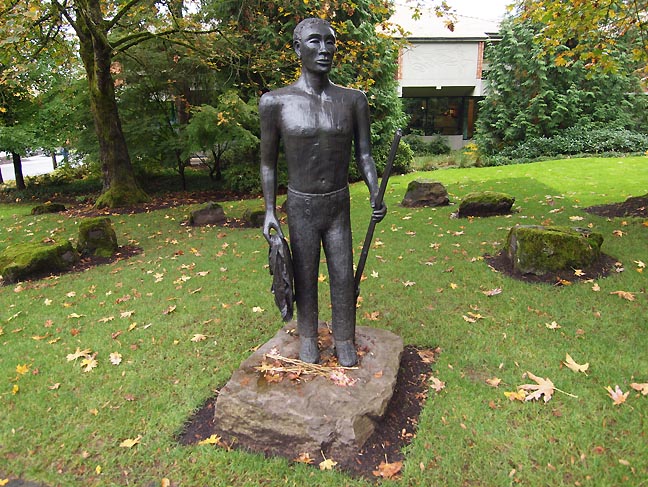

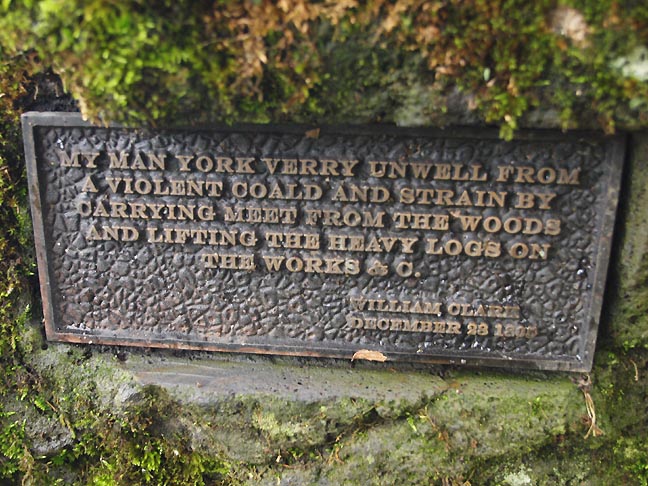

York: terra incognita (2010) photo Jeff Jahn Gabe: How did you end up at Lewis and Clark? Alison: Well there was this call for artists to do a piece with York and I saw it. Actually the architect who had worked with me on the Tubman project sent it to me and I had this idea immediately. I thought no way are they going to go for it with this black man with his shirt off and scarification on his back... and I didn't even bother applying. Anyways, Linda Tesner and the committee were familiar with my work from the Tubman project and encouraged me to submit my proposal. Still, any time I told people what I wanted to do with this piece they kind of gasped, so it wasn't an easy piece. Yet they said, “sure that sounds perfect.” And sure enough it made it through the committee and I've not heard of anyone that was highly offended. There was some talk of “you can't have his shirt off because that makes him kinda common or primal... you can't do that.”  York: Terra Icognita (detail) I thought, well you know we can't tell York's story without that. There are questions with all of these heroes. In fact there are questions of “how heroic was York?” Because the journals are written by his racist masters so you really only see him through these really tainted and muddy waters. He is portrayed as kind of goofy and doing all this dancing but at the same time he had all of these little achievements in terms of being responsible, feeding the troops and keeping the expedition from starving. So he definitely had his place but I also wanted to talk about the other side of the page. I wanted to talk about how he was treated and how he was the only man in the expedition that was not paid. He also thought he was getting his freedom but that wasn't realized for quite some time after the expedition either. It is meant to be a rough kind of history and so I came up here and did the piece. Then Linda (Tesner) asked if I was interested in doing a show and I said... yeah. G: Do you think there is a reason people haven't responded in a more outraged manner? Would you expect a different response if it wasn't Portland? A: Probably it is because the piece is on this campus and it is pretty small. Also, it was unveiled on graduation day so in the coming years. I'm hoping the students will have even more chance to respond respond to it in their big multicultural symposium. If I come back again Id like to have even more rapport. Id like to talk with other artists, maybe artists that are involved in public art and writers who deal in history and memory especially for minorities. Thus far it's been pretty much just the initial press for the papers. (laughs) So bring it on, I'm ready.... we'll see (laughs). G: (laughes) Bring it!  Harriet Tubman plaza in Harlem, NYC A: I guess what was so startling about the controversy over the Tubman project was because that was "my community." I also realized though that the money for that project came from percent for the arts where old buildings were coming down or being redeveloped in Harlem. So the community was being backed into a corner and there was push back from all of this gentrification. I think that was part of the tension as well, where she (Tubman's sculpture) was representing us being kicked out of Harlem because she was facing south. Whooooa, I did not see that coming and there were a lot of issues going around there. So she became the meeting place for all of these interests, which is good. I don't know if they are still pushing the mayor to turn her around, though they did start to see my angle in this where her insistence to help others and going south were supposed to help encourage the community to follow in her footsteps to some extent. She doesn't get tagged, so there is some effect. G: Do you think there is a difference between an audience that was oppressed and one that was the oppressor as far as historical work that relates to minorities? A: You know I don't know, everybody has got something to whine about. I guess the responses could be different but I don't know. What do you think? G: (Laughs) I'm not exactly sure. I imagine there would be a difference. A: For public art that is not necessarily historical... there is a great book about controversy and public art and it goes way way back to ancient times when someone didn't like a Dionysian sculpture. You put the work out there and everyone will have a different opinion. G: Maybe if we do our depictions as honestly as possible? A: Yes, for example with York there were all of these depictions of him. Some of them were like the Mandingo super buff dude, which is this whole other fantasy thing. Then there is another one where he is down at Lewis and Clark's feet, like a dog. Whoa... and that wasn't that long ago so really, like you guys didn't see where that depiction is kinda messed up? Another depiction has York handing the journal up to Clark... you just go oh my God. There are a lot of depictions out there.  Bound for Glory (front room) G: So the Hoffman Gallery is divided into two sections. Describe how you have the two differentiated? A: Yeah there's the public work in front and the other in back. The public work is very different and in a more historical context and it's very specifically about that time and place and there are maquettes in the front room. They aren't all public projects here in the front room but they all deal with historical subject matter.  Bound for Glory (back room) In the back room the work deals more with the psyche and the turmoil in my life. So that's a more personal experience. Some of them are political. It's funny because many many years ago (in the 80's) Lucy Lippard came to me and asked if I wanted to be in a book about art and politics. And I said, “but my work isn't political, it's mostly about me” and she said “Oh really” so I read her essay on political issues etc. and I hadn't really thought of my personal issues as political. But they were even though the ideas always came from a very internalized place.

So I kind of did this show backwards. The pieces in the back gallery are my community, a population of folks that I am in dialog with and It's actually kind of weird to see them all together since some of them are turning their backs on others and others are kind of facing off. I think it's actually the largest exhibit of my work that I've ever had so that was kind of interesting. It spans from the early 90's so the show is definitely stepping in a little deeper into my work. G: I definitely got the sense that the personal is political in this room. I got the sense that you were saying this is me, this is my life. A: And I guess growing up with my mother, a feminist... I didn't grow up with that struggle of having to go out and change things... I was able to simply go out and express my experience as opposed to going out there to fix things all of the time... although you still have to do that. You know there is still stuff going on. These are conflicted times with Obama and the Iraq war. I went to a peace rally downtown with my son and afterward he got these plastic samurai swords and was whacking stuff with them. Or with my daughter I find that she wears these little mini shorts and I ask her, “don't you dislike it when guys come up and say these lewd and horrible things to you” and she says “no Mom they don't mean anything by it.” So I'm having a hard time dealing with that but on another level she has confidence in herself as a woman. G: that is really interesting, it makes me wonder about a culture completely. For example I'm not a part of 16 year old culture... I just don't get the references but I wonder how much feeling like "an imposter" defines our world? ...and I feel like your work moved from just a historical affinity to a more personal ownership of these people's effect on the world. Was there something that happened to shift it from history to the personal? A: I think experiencing these things helped a lot. When I first moved to Harlem I worked in Harlem and my studio was in Harlem. I had this elated feeling where this club was here and that club was there... but eventually it became home and it was just Harlem. It just isn't that different from a lot of places though it was very different from where I grew up (LA). So the early work is definitely about the imagining of all of that history abut after experiencing the place you tone it down and get closer to what the reality was. You learn about the sad parts of the story and not just the raised fist and all of that stuff. Also it's because I kind of lived that stuff in the 60's. I was around 11 years old during the Watts Riots in LA. Later I was living in New Orleans during the Rodney King beating and some kids were so into it... all “burn baby burn” and wearing berets. But I had already seen something like that and seen the aftermath and who was effected or even injured during the riot. After you see who really gets targeted you realize there must be a smarter way to deal with this, but if there is something really outrageous you have to do something about it. It goes back and forth. Same goes for being really active in all the Obama stuff and you realize he has his limitations as well. But it still makes me angry because people blame him for everything and I say excuse me... it's not his fault. G: So often we forget history... almost like if I don't remember then it didn't happen. A: Or people turn it around and say well he's been in office for two years and I still don't have a job it's not his fault entirely. Sure some of it is but not entirely. G: do you ever feel like you are placed in a box that you don't want to be in any longer? A: I kinda feel like that but I've been in so many different boxes. I feel like the African American artist box has opened up and I think the feminist box has opened up. Also because I never finished a life drawing or sculpture course I have also been in a kind of folk art box but as the work changes the descriptions no longer qualify. Still I consider all of those figures in the gallery Black, because they are my family but it doesn't necessarily have to be about their struggle as African Americans. G: do you feel the limitations others put on you? A: I don't really allow them to do so. In the commercial realm with galleries I just bring the art to them, they don't have a say as to what I bring. Sometimes critics will take a piece like traveling light and say it is about lynching and they will take the easy road to understanding the work and they will put me in that box a lot actually. Yet one time someone thought they saw a dashiki and I thought where do you see a dashiki in all of this? Where did you get that? But I believe the work is only half done and it is up to the viewer to complete it. If someone has prejudice issues or feminist issues or racial ones they will bring those issues out in the work. So in a weird way it reflects more of the boxes that they are in rather than my own box. G: Why is that? A: Sometimes people mistake the criticism as doctrine or as the voice of the artist, which can be unfortunate but there is enough stuff out there and its diverse enough that it hopefully becomes clear that it is what we bring to the piece as well. G: Do people struggle with the fact that you are only part African American? A: Yeah, some critic when I had a show at the Hirshhorn said that this artist isn't black, she's more tan. I was like whaaaaaaat? This person had some real issues with color, like they wanted little skin samples. Even my Mom asked, “why don't you make some art about your Irish heritage?” Historically the black and Irish communities often got lumped in together and its probably why my Irish grandmother married a black man. They were basically put on that same boat and Jews and Catholics have been put on that boat as well. In New Orleans there were these huge longshoreman riots between the Blacks and Irish trying to grab onto that rung of the ladder and hang onto it. So even though these works are not specifically about being Irish they have a common experience. They can fit a lot of different backgrounds.  Coup (fg) G: Especially in this back room … in particular with these braids attached to the luggage. I think a lot of people can relate, I know I can. A: Its an interesting thing for me because I see all these works together, its alike a family reunion and I am starting to think about what the new direction is going to be. I collect certain things and I don't always know where they are going. Other times I know exactly what I want and its just a matter of executing it. York: Terra Incognita is on permanent display on Lewis and Clark College's grounds Bound For Glory at the Hoffman Gallery runs through December 12th 2010 Gabe Flores is an artist based in Portland Oregon Posted by Guest on November 30, 2010 at 15:51 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |