|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Picasso

I went to the Picasso exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum two days in a row. There was a lot to see. The work is from the Musee Picasso in Paris and will eventually travel to San Francisco and then to Virginia. It is always a little strange to finally confront work that you have looked at for years in books and magazines. Like most people, I feel as though I have a relationship with almost all of the paintings in the exhibition even though I was seeing them in person for the first time. Somehow every time we have been in Paris we have never made it to the Picasso Museum. For everyone out there who is not planning on going to Paris any time soon, seeing the work in Seattle or San Francisco might be a once in a lifetime experience. So ignore the lines, the swarms of school children and the constant fragments of narratives spilling from the omnipresent audio guides practically howling through the galleries and queue up. It is worth it. When we are talking about Picasso, it is never clear who we are talking about. Are we talking about the man? The artist? The father? The husband? The lover? Whenever I think about Picasso, I think about the Tibetan word Tulpa whose closest translation is "thought form." According to Wikipedia, it is a physical manifestation of psychic energy. When I am walking through the exhibition, there is Picasso as an artist and then there is the Tulpa.

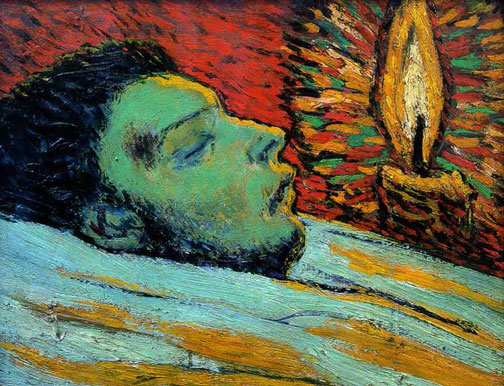

The work in the exhibition is from Picasso's estate, meaning that it is work he had in his private collection when he passed away. Given the number of masterpieces in the exhibition, the works on display are ones that Picasso never chose to sell. Perhaps they were too personal, too intense or served as talismans for the next evolution of his work. The exhibition begins with the Death of Casagemas from 1901. Casagemas was one of his best friends, and it is a striking painting. It is very small work that is incredibly thickly painted. You can see every brush mark on the surface. Looking at the painting up close, one of the things that struck me was a how thick the painting is over the light of the candle. The brushstrokes must be piled on at least 1/8-inch high, and that painting is over a hundred years old. If you look at long enough, you also realize that the perspective of the candle is all wrong. Either the candle really is over 12 inches across and is about to consume the body of poor Casagemas, or that it is something else, something that does not exist within physical space. On the one hand an art historian can explain that the candle that is still burning brightly after the demise of the physical body suggests that the memory and the work will far outlive the death of Casagemas. I think it is actually more significant than that.

In 1901, Picasso could not find the language that he wanted to articulate in the physical body of Casagemas. He did not know how to change and distort it to be able to create what he needed to say. This is little bit ironic because he would build his career by applying those same super-natural transformations to the human body. Perhaps it is a little reassuring that even Picasso had to learn a thing along the way. By making the flame, by rebuilding the flame, by literally re-creating the flame, he was discovering how to change the physical world to communicate and express the spiritual world. The real world is the starting point. It informs and perhaps inspires the paintings but doesn't define them. The real world that we live is specific and clear defined with easy to understand coordinates. One person is one person and most of the time is easily recognizable as such. The paintings are universal with a coordinate system in which up/down, left/right, forward/backward and inside/outside are not really important in and of themselves. Everything is one step away from becoming something else. Nothing is fixed. When he makes a portrait is it about one person or all people? For me, this is the world of Tulpa, the spirit world inhabiting a physical form and is well-documented Picasso found an incredible resource and precedent in Tribal Art by people from all over the world.

I once had the opportunity to tour the Jolika Collection of Oceanic Art at the De Young Museum with its owner, John Friede. Friede said something that I would never forget and echoed in my ears as I walked through the Picasso exhibition. Friede said that while these figures may look human, they aren't, and if we mistake them for being human, then we may miss what they are really about.

This was Picasso's great discovery. He is not showing something new, but something very old. As a culture, we have forgotten it. His work seems so odd because these expressions were somehow written out of the Western canon, probably sometime before the Greeks who were obsessed with finding the perfect form of the human body. When he is looking in the dark cases of the Palais du Trocadero that were filled with art outside the Western tradition from all over the world, he is not discovering anything new. Rather, than experience is reinforcing what he had already instinctively understood about painting, namely that art is never restricted to the physical world that we see only with our eyes. Everybody knows this except for the "civilized" Western societies. There are many ways of seeing, and it is the blending of perceptions from all of the possible cultural wavelengths that informs our own experience. It was not just the forms of the sculptures, the power figures, that he had encountered which led him on the path toward Cubism, it was something much more important. It was intention and the awareness of all of these paths of information that could find physical form in his work. I believe it was a lesson that he never forgot. To make sure he never forgot, he had a wonderful collection of Tribal Art from all over the world that he lived with until the end of his life. I think that this is why when Matisse had an opportunity to have a comission to paint the Chapel in Vence, the whole idea of it left Picasso cold. I do not think that this was because of Picasso's ideology but that Picasso was communicating those very same ideas and experiences in everything he touch. He did not need the religuous symbols, there were extraneous to what he need to communicate. When Matisse takes the Chapel comission, I think that Picasso realizes how dramatically different are the ways in which they approach their work. Religion gave Matisse's Chapel purpose. Picasso had long ago discovered the same purpose in everything that he came across in his daily life. Picasso probably thought he was making a chapel every time he picked up a paint brush.

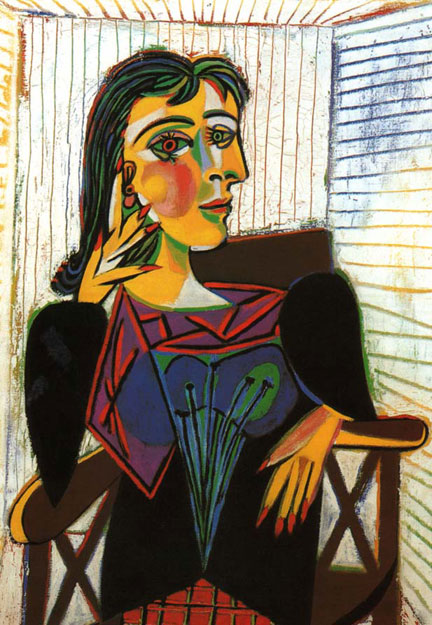

Not surprisingly, Picasso's work is often a fusion of opposites. He seems to see Dora Maar as both a specific person and a personification of the qualities of both women and human beings. It is the shift between the specific and the general, the microcosmic to the macrocosmic, the real and the mythological, the physical and the spiritual that drives the experience of the work and probably partially explains why the paintings are so compelling nearly 100 years after they have been completed. The part expands to become the whole. The whole is reduced and concentrated in the part. Is the portrait of Dora Maar of a single specific human being or something more transcendent and universal? What about when we look at a statue of the Virgin Mary? Or the Buddha? There is also another parallel. Power figures in Tribal Art and religious icons are objects of worship. Are Picasso's portraits objects of worship? Of both a specific person and women in general? As both an individual human being and humanity as a whole? Only Picasso would be able to say for sure, but they look like objects of worship to me. Consider: if we were to state the opposite, that they aren't objects of worship, that they are only intensifications and a literal documentation of everyday experience, we would seem to lose so much of what makes these paintings so compelling and enigmatic. Dora Maar was a human being, but her portraits aren't. The painting is part Dora and part Tulpa. One can never take credit for the other. There is another precedent in that Caravaggio would use prostitutes as models for the saints in his paintings. I suppose that they were available at the time and got the job. Does that make his paintings about the prostitutes he used as models or the saints, which were the subject matter of the painting? Picasso was building another kind of reality in which this event, this portrait, could take place. After all, isn't the presentation of the work at the museum yet another form of worship?

While the exhibition as a whole is extraordinary, looking at the work within the context of 20th century art history, there are still some things that bothered me about Picasso's process that might be helpful for understanding his work in general. The first is his treatment, or recognition, of the spatial effect of the solid edge formed by the boundary of the canvas. Almost every single Picasso painting has the subject matter concentrated in the middle of the canvas. I think that this serves at least two purposes. It is buffered on all sides from the flattening effect of the edges of the canvas. This allows his work to be more spatial, more three-dimensional, to generate the space of the painting through its own internal relationships rather than being defined by the boundary of the canvas. This is especially pronounced in the Cubist paintings in which all of the space is in the middle of the canvas and there are only a few lines that extend outward toward the edge. It was a technique that he would use for the rest of his life. It also enforces that Picasso was creating virtual worlds within these paintings. He is not interested in the slightest with how the space in a painting might relate to the larger space of the gallery.

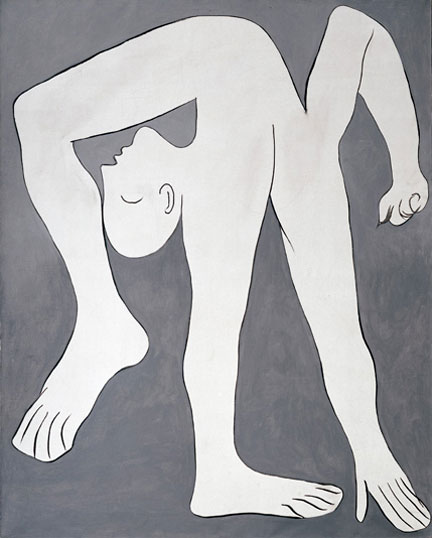

The third point is that at least some connection to the physical world is essential for Picasso to generate power and traction in a painting. A the end of 1911, right at the time in which Analytical Cubism seemed to be losing steam, Picasso must have understood that the he was confronted with the opportunity to make a totally abstract painting. Instead, he simplified the rules of Analytical Cubism, defined space through a series of large flat planes and developed it into Synthetic Cubism, a style which he would continue to employ until at least 1919 and that would go on to inform his work for the rest of his life. It seems like paint as its own material and the physical possibilities of the medium to generate the content of a painting did not interest him. He left the door wide open for Malevich with the Black Square in 1915. Picasso was still grounded in the world in which he lived. It was the people around him, his studios, his pets, and his lovers that drove the content for his work. They were his jumping off point, his bridge from the specific to the universal. Of course, these two ideas would go on to define 20 th century art: painting as a physical object that extends to the edges of the canvas, and a concentration on the physical properties of the material that allows the viewer to participate in the space of the work and its presence in the space which it is shown.

At the beginning of the 21st century, while it is clear that we have gained some new approaches to art since Picasso, I would also say that we have lost some as well. Picasso loved to pun shapes. Fruit could become breasts, a bicycle seat and handle bars could become a bull's head, thin tubes of wire could suggest a human body. Today, artists tend to be much more literal. If an artist wanted a bull's head they would probably use a real bull's head or at least a detailed anatomically correct copy of one. If you wanted to explore the human body, someone today is much more likely to just pick up a camera and take off their clothes. Sarah Lucas is of course the exception in this case as she has a made a ton of work about the punning of shapes and the human body, but I still feel that her approach is relatively rare. As a whole, we seem to be much more literal today, more real. If we use a material, we are specifically using it for the unique qualities of that material. Even when are being superficial and synthetic, we often lack the material invention and imagination of Picasso's best work. In Picasso's approach, everything is interconnected. Everything he touched was just one small step from being turned into something completely different. The last thing that stood out to me as walked through the show was another similarity with Tribal Art and that was how important the context is for the experience of the work. Even though Picasso's work now fills an innumerable number of museums, except for paintings like Guernica, one never gets the feeling that he was making work for museums. When you look at his paintings up close, they are too brutal, too rough, too unfinished to seem to belong in a museum. I think at some level Picasso understood that bring this work into museum was to destroy the idea of the museum as place for perfection and aesthetic reflection but without a soul or a life. Most non-Western societies did not have museums although that is changing now. When the work was no longer compelling it was either stored or destroyed. It reminds me that a museum is an idea. In Picasso's case, look at the work is to participate in the work. I think it is that the directness of the work is one of the qualities that make it so compelling. To place the work in the museum is both to change the work and the institution. When you look at photos of Picasso's studio, one sees the work in piles; the table is absolutely covered with everything. There does not seem to be any flat space left anywhere within a quarter-mile radius where someone else would be able to put something down. But yet all of it is important. All of the piles are talking to one another. The paintings are talking to sculptures, and everything seems very natural. I think it is the quality of naturalness that is most frequently lost in museum exhibitions. The work is of course very valuable and needs to be protected, but can you imagine what it would have been like to dig through his piles in Cannes? What would you have discovered? Today, everything is behind glass, thoroughly documented, photographically examined and very carefully explained in a detailed audio tour. I can't help but to think that we lost something along the way, but I also fully understand that these steps were necessary because the alternative would have been a disaster.

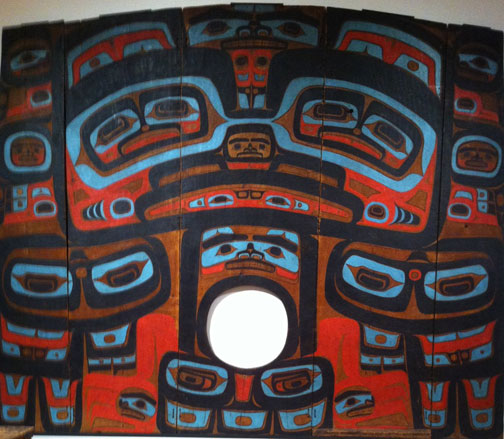

Because so many visitors are coming to the Seattle Art Museum just to see the Picasso show, it means some of the other floors in the museum are very sparsely inhabited. Both times after walking through the Picasso show, I found myself on the third floor walking through the Japanese collections to the Aboriginal paintings and then finishing in the rooms of the Northwest Coast Indians. In one of the rooms, there is an absolutely stunning screen that is painted on very large boards. Like most Tribal Art, it comfortably straddles both the physical and spiritual worlds. The beings in the screen are not entirely of this world, nor are they entirely separate. It was its own kind of Tulpa, its own kind of psychic manifestation that temporarily materializes in physical form. For me it seemed to encapsulate everything that Picasso was working toward in a completely different way. It reminded me that Picasso was not telling us something new, but something very old, something that as culture we have forgotten along the way. He brought it back and made it fresh again, and decades later, he is still showing us how see the world with new eyes.

Posted by Arcy Douglass on October 31, 2010 at 7:07 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |