|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

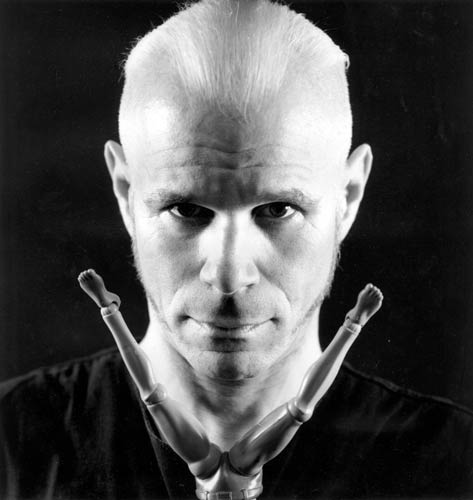

Interview with Charles Atlas  Charles Atlas (photo Josef Astor) GW: Lets start with a brief synopsis of your work. CA: I started out doing media dance combining dance with video or film. I worked with Merce Cunnigham for years. I have done feature length documentaries, multi media video installations, I've done live electronic performances and since 2003 I have been mainly focused on exploring different ways of using live video with performance or as performance or in installation.

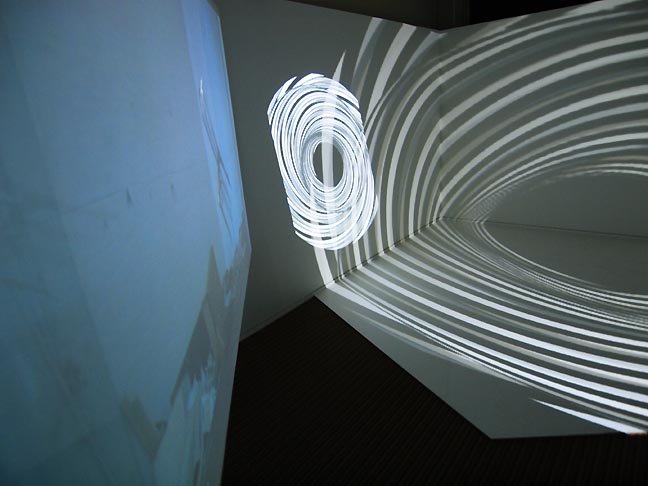

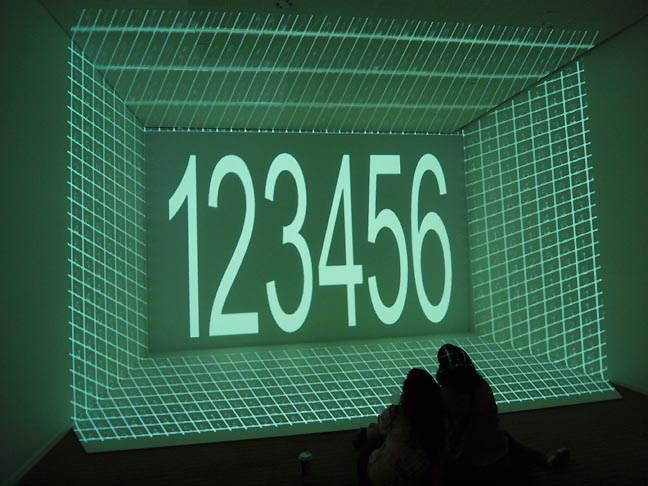

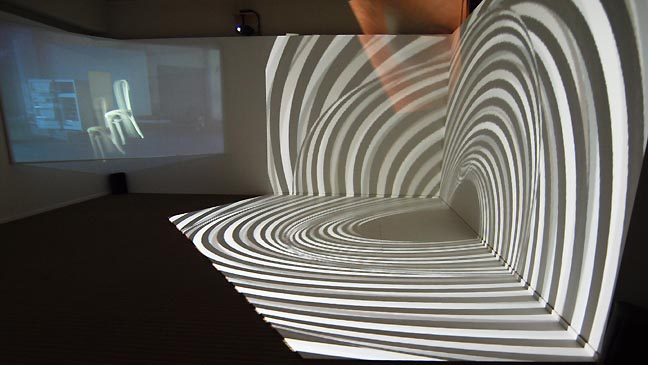

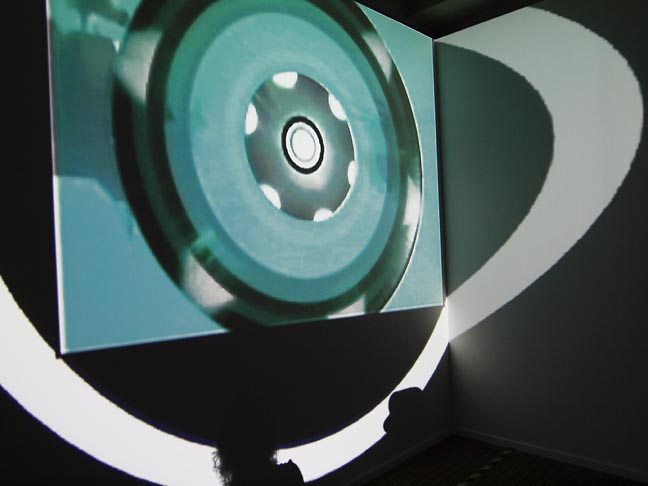

Charles Atlas Tornado Warning, TBA install (photo Jeff Jahn) GW: I would like to talk about Tornado Warning, the piece you have installed here at the ON SITE section of the TBA festival. CA: I had a retrospective and I realized that I wanted to show recent work. But all my recent work is live so there is nothing that exists. The last two pieces I have done have not been live - no live elements - but are influenced by the work I did in live video - so I could install something and then leave. Which was good. This piece - I made the first version of it in 2008 and I showed it in a gallery in London - It's called Tornado Warning. It was conceived as a two space piece, for two adjacent rooms. It has been done in various configurations but this looks like it is going to be the best ever. I'm really excited about it. The basis of it - aside from arising from some feelings I was having at the time - was that it was a piece that had maximum contrast. When I started out with this piece I wanted it to look like someone else made it. I wanted to try to make it look like nothing else I had done before. It was a challenge. I probably didn't succeed, but anyway, I tried. So I wanted to make two very contrasting images, contrasting in every possible way. One room is really chaotic and has sound and four channels of video everywhere and whirlwinds. Everything is spinning in that room. The other is silent and contemplative and uses straight lines and numbers. I wanted to make the second room as nonhuman as I could manage.  Plato's Alley, TBA install (photo Jeff Jahn) The other room was of course more about mixed up feelings. So this room is black and white that room is color, the whole feeling of it is different. The reason it is called Tornado Warning is because when I was making it I realized that the images that were coming up for me were alarming and threatening and disturbing, and it reminded me of my childhood. I grew up in Missouri where we were sent home all the time when there were tornado warnings. We sat in the basement and waited. Fortunately nothing ever hit our house. It was this feeling of apprehension. [Tornado Warning] kind of represented the reality of chaos and [Plato's Alley] represented a dream of order. This is only the second time its been shown. We made specs for this room but didn't get them right so I had to slightly redo the video. I thought I could redo it more easily. It was very very complex to figure out in the first place. I try to make more than elaborate notes about what I am doing in the first place because I can't figure out what I did once I've done it. There are so many steps and layers but no matter how much I write down it's always an issue because I just don't remember. It takes like a day or two days to get back into the head where I was. GW: When did you make this piece? CA: 2008. November. GW: And how did you generate the images? CA: This is all computer generated. I did it in After Effects. GW: How long did it take you to make? CA: I'm really a last minute person. I think about a piece a lot and procrastinate and then do a lot at the last minute. This one however I didn't know where it was going. I started it. I didn't know what I wanted to do and it just kept evolving - kept building until it was over. So, I think I did it over a period of about a month. Not-full time all the time. I would work a day, another day. GW: Do you find your creative process is different in this kind of work as opposed to the work you were always present it? CA: Well, the work that I was always present in is different from all my other work. It was 2003 when I started this other kind of work. I have done lots of pieces, nearly two-hundred I guess, various lengths, mostly long. The last one, I remember I did this piece called Ranier Variations about Yvonne Rainier, whose a choreographer. And my plan for it was very, very detailed and when I got into the editing room I just sort of took a deep breath, because I know what that feeling is when you are all by yourself and it's a long process. I knew I could make a good piece about it but its just the number of hours I have to put in to do it. I enjoyed making that piece, but I really felt like I was doing needlepoint. It's not that I don't enjoy that, but when the technology became available and the situation became available - a dancer invited me to make a video and costumes to go with a dance that he made - I said that I didn't want to do a video landscape that you dance in front of, I think that's boring, and if you are live, I want to be live. That was in 2003, the technology was just [emerging]. I could do something off my laptop but it was really basic. We made a piece together using three live cameras and live processing and I was part of the piece. It was really liberating for me. And then when I started doing the kind of work that I am doing in the theatre on Friday, which is like live video improvisation in collaboration with a musician, that was the most fun I had in a long time. If I had to do one of those pieces, a 45 minute piece with that much detail my old way, it would have taken six months at least. And this was done in an hour. And it was fun! I did it a couple times and eventually someone else asked me to do something, another dancer, to do video. I wanted to do something live but it was to specific music and I decided to make a sort of backing video that went with the music and I would improvise on top of that. It really was like a score and I did the piece six times and by the end I was really bored. I could do it so it wasn't that interesting to me. A friend of mine came up to me and said, 'Oh I really like this piece compared to the one you did three months ago, which worked some of the time, but this one worked all of the time.' And so I thought, 'Oh, the audience.' It was no question which one was more fun for me. But I think in the live improvisation arena audiences have different expectations. So if it's too slick they don't like it. So I have started to use a little more structure that I never quite achieved before, at least it had more of a feeling of structure. In those kind of pieces, the piece is a length of time, a beginning clip and then a set of may be 200 clips that I limit myself to. Coming up with those clips is really a process like sculpture. Its really time consuming, this whole live thing, but it's interesting. You play around and then find images that don't go and then you get rid of them and you keep getting rid of images until all those that you have seem to adhere to whatever it is that you are thinking about. So that is that kind of work. I have also been doing this piece called Instant Fame which is a live installation in the gallery. I did it in New York and in London. Again the space is set up into two spaces. One is like an intimate studio space, where the person comes - either by appointment or they just show up - and I am there with a person with two cameras and we we make a portrait of that person. Then it is shown live, on a big screen in another space. You can either watch the result or the process. I didn't want it to be like, Oh, he's doing that and it's becoming that. I wanted it to be two different experiences. I've done that a couple of times. In New York I did it in a gallery for 3 weeks and made about 60 portraits. When I did it in London people were a little bit more reticent. I kind of asked for show offs. I didn't always get them but I know a lot of performers and I think at this time, because of Youtube, people are more performative in general. They're doing what I was doing before that. It kind of looks a little bit like Youtube if you processed it. I did it in London and I am probably doing it again in Australia. That's another kind of installation. Another installation, a similar idea but a much bigger scale, the live 3 day installation in collaboration with Mika Tajima, a New York artist, and the New Humans, which is her music group. We were in the SFMOMA and it was the same situation, she made an environment, we had talks and performances. It was more of about spoken word and music throughout the three days and I was mixing live the entire time. The theatre adjacent was showing the result. You could go watch in the theatre or you could watch what we were doing. We are expanding that and doing it again in London next year. GW: What is the significance of the numbers 1 - 6? [In Tornado Warning's quiet room, Plato's Alley] CA: Somewhere I read that the maximum number of numbers that you could keep in your head at one time was 6. I keep trying to find where I read that and I haven't been able to relocate it. I didn't want to do something with all the numbers. I was really thinking about the idea of numberness. I really didn't necessarily want to use numerals because they were like a human script. So that is why I started out with the shapes, and I didn't want to have biomorphic shapes, so I could fit 6 bars in a good way inside the screen. That is how I came up with 6. I didn't really exploit that idea too much. I didn't do complicated numbers. This is the first piece I ever did with numbers. When the numbers 1-2-3-4-5-6 are like a dance, like short solos, and then there is the curtain call when they all come out together. GW: Do you notice a difference between the way that different disciplines collaborate, performers versus visual artists? Seems like you have worked with both.

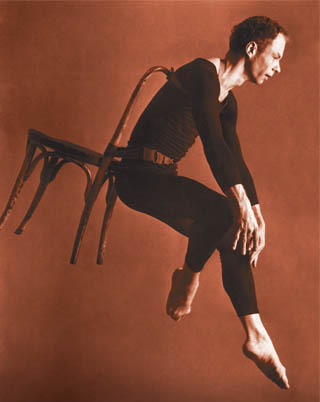

Merce Cunningham CA: I started out collaborating with Merce Cunningham, which is the best luck anyone could have. It was never better than that. He had developed an idea of collaboration because of his work with John Cage and Robert Raushenberg and Jasper Johns. He had had great success by letting everyone just be in tune with each other and do whatever they wanted. Everyone gave the maximum and it sometimes worked and sometimes didn't work and that was Ok. Interestingness was the hallmark at that time rather than good or bad. I worked with Merce for 10 years in that environment, I did costumes and lighting - I made a few films then but we really didn't do films in performance. I collaborated with him on 10 pieces. We were very close and we worked close and I was very young at the time and so I was very adaptable to his aesthetic. When I moved away from that situation in 1983 I started working with all sorts of people, mostly dancers and performers. Some collaborations work better than others. I have really done a lot of work in collaboration. It works best when you have love and respect for the other person and everyone is giving and not judgmental, and it's working. I've also been involved in some...arranged collaborations, let's say, and I have never had one that was as successful as a natural one. For me they are always interesting because they stretch me in ways and I do things that I wouldn't do otherwise, but the result...I did one collaboration, recently, in this period with a Spanish choreographer and a musician, and we were trying to deal with the issue of - when you have video in performance it can really upstage the live elements if you let it. If you don't control it. So, there are various ways of doing it. You can do the performance and alternate so that you're not competing. There are lots of ways. But we decided to try a way where everything was focused at the same place so the dancer was really related to the image. It just about killed me. It was a 40 minute piece. I realized when I got into it that I would be doing things I would never have done otherwise but didn't realize how much. I would say I was in a panic for 3 months because I knew I could barely ever finish it in the right way. I spent two-thirds of my time just being in sync with things rather than other things I could have done. The result proved to me the validity of the Cunnigham Cage way. Because everything went together so closely. It was not as interesting as the audience making, or stretching to make a relation. Mika is the first visual artist that I have collaborated with. That is working great. But again, it is one of those situations where it is just like, love. We like each other and we enjoy being around each other and so it works. I would recommend, if you are collaborating, just find something that you really love and then that's what you should work with on the other side. Because that will work better.  Charles Atlas Tornado Warning, TBA install (photo Jeff Jahn) I like to have givens. That really helps me to have certain givens. When I made this piece [Tornado Warning] I went to the place I was going to show in and I made a piece exactly for the space. It was a long narrow space. I wanted to have something on 3 walls and I realized they were all going to be in sync and it was going to be a nightmare to do, but I really wanted the piece to come all the way down. But given the space there was not a projector that could give adequate throw from the other side at all, not even close. That is why I came up with this piece and figured out a way to make it 3D in a different way. GW: Did you think about how it created optical illusions when you were making it, with all the different lines? CA: I just did it. I knew something was going to happen. I did an experiment so I knew something was going to work about it, but I was just thrilled when I saw it finally, how the lines exactly went. I knew they would come out, but I didn't know...I couldn't figure that out. GW: How did you come to video? CA: I've always wanted to make films. I wanted to make movies when I was a kid. I started out, when I came to New York, making Super 8 and 16. Then in 1973 or 4 Merce Cunnigham wanted to make videos because John Cage had an idea that if he made videos he wouldn't have to tour anymore, he would just send the videos out. That was the basis because John didn't want Merce to tour anymore. I learned video from a book, from Spaghetti City Video Manual, and then I taught it to Merce and that is how I started in video. At that time the video and the film community were not friendly. Video people thought film was a four letter word, which it is, but...I never made the distinction. For me it was always about making images and making a project and whatever money I had, whatever means I had that's what I was going to use. So I was a bastard. Now, everything is digital. So I came out on top. GW: Did you have set design background as well? CA: Everything I learned I learned myself. I didn't go to school. I dropped out of college after two years because I went to a liberal arts college where you couldn't get credit for any art things and it turned out I was more interested in art things so I just came to New York. I was lucky that I fell into the circumstances I did. GW: If you were ever going to become proficient in another medium what would you choose? CA: Well...It's probably not going to happen. I learn things as I need to. I'm not very handy so I am never going to be that crafty about making things. I would love it if I was good at writing but I am terrible at it. I don't know how that will ever happen. There is a lot to explore. I am very happy to be in film and video. I don't feel like I have nearly explored all the possibilities. I try always to do something that I haven't done before so it remains interesting and there is plenty still to do. And the technology keeps changing. I am not mister-state-of-the-art, in fact I consider myself rather low tech compared to the high-tech guys. GW: Is that because you feel what you are working with is adequate or is there a kind of pride in doing more with less? CA: No, this is already very expensive and hard to arrange. I think, this is really simple, but, not as simple as I think, I guess. There are people that always use huge projectors, it's a question of money. And I'm not working in big outdoor installations where there is a much bigger budget. It's not like I wouldn't. Then there are the people who are working in 3D animation which is a whole other kind of software to learn which I haven't done. School is where you learn everything these days so what you come out with is usually where you start. I really taught myself everything, from computers, everything from scratch. GW: Are these two rooms one piece? CA: They have two different names but I consider them one piece. GW: Did Kristen Kennedy ask for this work or did she allow you to choose what you wanted to show? CA: She asked for this work. She'd never seen it completely. There was a version shown in New York which was just 3 channels that was really kind of lame. I agreed to do it and then I was sorry. But I did. In a much smaller space. It worked Ok but not like this. This is going to be great. I'm really thrilled.  Tornado Warning, TBA install (photo Jeff Jahn) GW: How do you feel about working in the context of an old high school? Do you feel that it informs what you are doing at all? CA: Having this much space is great. Originally I thought - I kind of like the idea of working in odd spaces but I didn't realize how many pristine needs I had until I started thinking about it. They had to remove lights here that they thought they wouldn't have to remove but it wasn't going to work with these lights hanging down. But they [PICA] did a great job making the space for me. I'm really pleased. GW: I have an interest in creative lineages. I recently interviewed Nina Katchadourian, who is also in this festival, and found out that she studied under Alan Kaprow who in turn studied under John Cage. Did you work with John Cage as well? CA: I was quite young when I joined the Cunningham Company and encountered all of that for the first time. John was really a great person and interesting and I tried Chance Method; it didn't work for me. We were allowed a lot of freedom so when I did lighting I really lit the dance. I didn't do lighting like weather. I just didn't think it worked. I was always for what worked and I thought sometimes it was too amorphous and I would highlight...anyway, I did my thing. And it turns out now, in my later work, I am much more of a "Cageian" GW: I suppose you have a lot more experience now so you know how things work. CA: You know it's just that I am really much more open to whatever happens. GW: Obviously the technology allows you more control as well, in an immediate sense. CA: Oh, totally. Also, with everything I do, it's interesting, you could have a randomness factor. For John Cage it would always be set on completely random. But I thought it was quite funny, once in John's experience, at a certain point, when he was using the I Ching he wasn't casting with coins anymore, he was using a printout from Wesleyan that had figured out chance - so he would just have reams and reams of print outs - for the next question it's a 1 or 6 whatever. Later on he found out that the algorithm they were using wasn't actually completely random. By chance, it was chance that wasn't completely chance. GW: I have found that I am interested in setting up frameworks that random things can occur within... CA: Well, the key to working with chance is setting up the structure of what elements are determined by chance. And I also had my own idea of how they came to chance. It was personal, they wanted to get their egos out of it, because of their personal issues. So, I really respect John, and have always, but I was really more of a Merce person. Merce used chance pretty rigorously, but he cheated - being a Catholic [laughs]. John was a Methodist so he never cheated. Merce used to - I worked very closely with him so I saw his working process - sometimes used what he called poetic license. I have seen people over the years talk about the Chance Method and they say, 'We used chance' but, only when it works. That's kind of cheating but in a much worse way. It's really like not using it. GW: You talked about the quiet piece in the exhibition [Plato's Alley] being a contemplative work, but... CA: You didn't find it that way? GW: No, not at all. CA: The shakiness? GW: The shakiness, yes, and the flashing and blinking, I found it very stimulating actually. CA: May be contemplative is the wrong word to use. I don't expect people to just zone out. It really has a quality of a film. I realize even for me there are funny parts, if there can be funny parts with just numbers. I guess the basis really was - I was searching and searching for the least...human, that's how I came to the idea of numberness. I thought, there must be numberness without humans. But how do you - I could never philosophically get to the nub. I had a discussion with a physicist who tried to explain the whole thing to me before I worked on this piece. The whole idea of number and binary, it informed the piece but I don't think I really completely understood the ideas. GW: When the numbers appear in the grid I immediately was reminded of certain scenes in the Matrix. Was that intentional? CA: Well, I've watched the Matrix practically hundreds of times. I love that movie. All three parts. But it does in a way. Things represented by numbers. What do numbers mean? Is it scary? The nonhuman nature of it is really what is the essential part for me. And then doing something with that, I made a little piece out of that. I normally don't work from an idea at all. I don't even know what I usually work from, I usually just start with whatever occurs to me and then ideas accrue and sort of grow. GW: So it is more of an intuitive process? CA: It is completely more of an intuitive thing. GW: They didn't pound that out of you in art school because you didn't go. CA: I didn't go to art school. That's what I hate about the art school aesthetic. This whole overlay of conceptualism. I mean it is just ridiculous. The things that people write about. I am definitely not about school. GW: It makes my shoulders hurt to think about. Do you feel successful with [Plato's Alley] in attaining a nonhuman result? CA: I feel that is where I started and I feel successful in that I like the result. And what it turned out to be, you know the people who know my work would probably recognize that it is my work but as I said, I was really trying to make something that looked unlike anything I had made before. Sometimes I have had formal elements but never that formal. Posted by Gary Wiseman on October 03, 2010 at 11:07 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |