|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

The Often Monochromatic, Sometimes Off-Color World of Jacques Flechemuller at PDX Contemporary It is an assumptive thesis based more on memory than research that proposes

color television brought about the demise of a perfect world. There was a time

when movie theaters showed newsreels and film shorts, and newspapers had fewer

photos and more illustrations. This was in the black and white world before

and after World War II. Oh, there was color in some media, but it was a rarity,

yet more of a harbinger. Technicolor, Kodachrome and other similar technologies

aided to the end of a wonderful, simpler era.

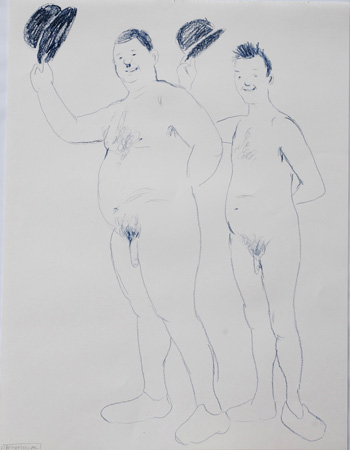

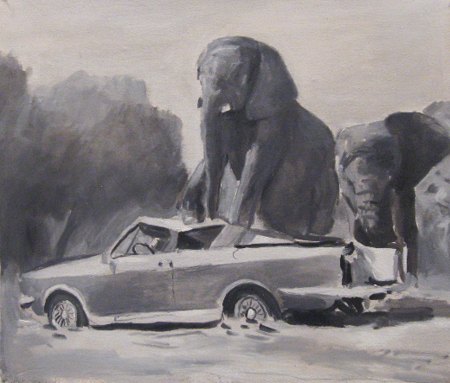

L+H 2009 What would a perfect world look like? It would have young children sitting cross-legged on the floor watching a small, 1955 television screen, laughing with glee. Chimpanzees in dresses do tricks that make them look more human, and old Laurel and Hardy films make monkeys out of everyone. It is a formative world for those children. Sixty-five years later, chimps neurotically masturbate in real-world captivity and, for Jacques Flechemuller, Laurel and Hardy are naked and fairly well endowed. How can one not chuckle? What went wrong? Of course, such an absurd notion must be met with a smile; still, a monochrome world carries a certain authenticity, and one unfettered by the complexities that color brings to understanding. The world is necessarily flawed. Only nostalgia would keep a simple world, but the pain of that impossibility breeds entrenchment or a wry subversion. Rarely does one wholly escape one or the other, and if one is not careful, the flaws compound, and turn against one another.  RIALTO MERCATO, 2010 Fleichemuller’s subject matter seems often to address an earlier time, and while Flechemuller’s paintings are done with wit and a painterly style reminiscent of Gerhard Richter circa 1965, the fragile simulacrum begins to oxidize in his artist’s statement: In the country, in the south of France, on the road to the river, the peasants have painted big signs that read: "MELONS 3 for 5 euros," or "TOMATOES, ONIONS, POTATOES 300 meters," or "GOOD WINE" or "CHERRIES AND STRAWBERRIES, HERE". Big white letters on panels of scrap wood. So simple, so efficient. Hand made, not perfect, but... PERFECT. I always admire these "objects." Always want to steal them and hang them on the walls of my house. A bit jealous of their beauty?...perhaps! These peasants have no idea how moving their signs are for me. So especially artistic because they are not "ARTISTIC." I dream to have the guts to do Art like that. So hard to be so simple. It is entirely possible for an art reviewer to completely miss an artist’s intention. Or (after an assurance that the use of the word “peasant” is not considered a pejorative in the language from which it originated as paysant), it may be that too close a reading suggests less of an intention and begins to flush out a disposition. The peasants are producers of quaint objects and not farmers advertising their products? (And the folks who own Queener Fruit Farm outside of Stayton, Oregon wonder why their farm signs get stolen. Who’s to say vandals don’t have a sense of humor as much as entitlement?) It is not the farmers’ signs but the quality of what they are selling that matters. Of course, all Flechemuller has to do is paint one of these signs for himself, even though such a painting would lose its authenticity. And to paint with such utility… who calls that art, anyway? It is a quandary. What’s more, his statement is about painting technique more than the subject matter of his work. Nonetheless, he appreciates the straightforward, “not ARTISTIC’ but “Art”. Nothing like Flechemuller’s work, yet everything about his work. The man can paint but he downplays his ability by way of subject matter.  LANDSCAPE, 2010 What seems to be missing in Flechemuller’s artist statement is the wit that is present in some of his paintings. As in all humor, frustration leans on irreverence as a saving grace, a satire. And there is no doubt that Flechemuller has a streak of the funny, poking fun at himself as much as the characters he repurposes for his coy ploys of social commentary. However, such is not the case in all of his paintings, for some of what the artist might consider funny or satirical, shows the same short-sightedness as the romantic notion he has of the peasants’ lives. After all, what can one say about Colette,” a portrait of a woman pinching and pulling her nipples upward? Naughty? To Flechemuller’s credit, he attempts to add levity to what has historically been serious business, that of painting. Yet it is the painterliness of his work that seems out of place, as if Flechemuller is purposefully trying to remove the dignity from his practice. When he draws instead of paints, whether on paper or canvas, the work seems more successful in that those works are more fitting to the cartoonish nature of much of his subject matter. On the other hand, paintings such as “Landscape,” “South 4th,” “My Nephew from Toulon,” or even “Beauty Mask” are the most intriguing for they suggest allegory is at work. Flechemuller has had five solo exhibitions at PDX Contemporary, and has been in a few groups shows as well in the last fourteen or so years. To exhibit so frequently, he must be doing something right that connects with the area’s art appreciators. Yet, in that time, there is precious little written about his work. True, mention has been made regarding his ability as a painter; instead, it may be that jokes are better left unexplained, or perhaps much of his subject matter may not be something one talks about in polite company. Posted by Patrick Collier on October 25, 2010 at 10:30 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |