|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Sol LeWitt Wall Drawing at PAM The wall drawings of Sol LeWitt, though dated by more than a decade, still resonate with the current artistic community. Sol LeWitt was a courageous artist with powerful insights as to both the workings and processes of art. He questioned drawing, painting, and sculpture unabashedly and directly with explorations of simple geometric form, color, and line. He also had the foresight to create work that would continue to spawn beyond his own lifespan, leaving us with gifts like Wall Drawing #304 currently on view at the Portland Art Museum.

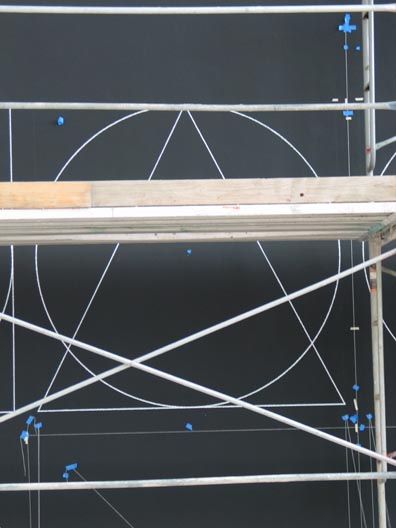

Sol LeWitt Wall Drawing #304 The construction of LeWitt's drawing in the Schnizter Sculpture Court was completed by Nobuto Suga and Aaron Doyle. For six days they worked on massive scaffolding carefully following LeWitt's directions and diagram. Every measurement and line required careful communication between both artists, as well as constant attention to LeWitt's instructions. The artists' process represented a union, which I found had a great deal in common with the subjects of LeWitt's work. Their cooperation spoke metaphorically to the interlocking shapes patterned on the wall behind them.  Aaron Doyle on the scaffolding LeWitt's work eloquently questiones the boundaries of art by separating the artist's hand from the product while maintaining indirect control of the marks. LeWitt disengaged personal history from his subject matter and mark during a time of heightened expressionism. LeWitt utilized a systemic pseudo-scientific approach to making art, relying on mathematical patterns and logic instead of politics or personal evaluations. The idea of removing emotional and environmental influences from the work would become vital components of both Conceptualism and Minimalism. The beauty of LeWitt's art, aside from its aesthetically pleasing form, resides in its commanding simplicity. In fact one need look no further than the title "all combinations circles, squares, triangles, rectangles, trapezoids, parallelograms superimposed in pairs" to know what the work is about. Verifying that all combinations are indeed present is task easily accomplished by most any viewer. Yet one still feels gratified from the satisfaction of double-checking LeWitt's math. Such accessible subject matter is inclusive to even the most inexperienced museumgoer, an admirable trait in any artist.

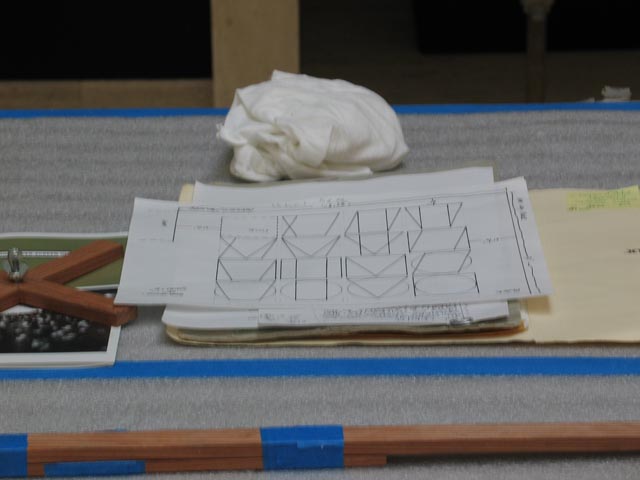

Though simple in its form, LeWitt's work is indeed layered with implications about authorship, originality, and our definitions of painting. His wall drawings in particular expose relationships between the physical manifestation of an object and its conception, as well as the rigid nature of a paintings' support. LeWitt's directions for wall drawings complicate the viewer's location of the art itself. Is the art in the wall drawing or the detailed instructions LeWitt created some forty years ago? Does the diagram become art once it has been made tangible or is the concept of the work a piece of art in of itself? LeWitt's inquiries approach fundamental structures of drawing, from conception to realization, and force his audience to reevaluate the boundaries of art. A painting's inherent flatness concerned LeWitt, which may have led to the evolution of his wall drawings. He saw awkwardness in the separation between the canvas and the wall, opting instead to have the painting directly placed on its environment. By doing so LeWitt manifests an idea without building an object/artifact. Instead, the painting becomes part of the architecture of its environment, lacking both the mobility and lifespan of a panel or stretched canvas.  Aaron Doyle and Nobuto Suga Because LeWitt's wall drawings may be created ad infinitum one cannot help but wonder where the original and the copy exist. If the drawing has already been painted on a wall is the next iteration simply a copy? What happens when two versions of the same wall drawing exist? Perhaps all iterations are copies of the schematic LeWitt designed, yet most viewers probably would not consider the small piece of printer paper covered with dimensions and directions to represent the work itself. LeWitt believed that the wall drawing was required to realize the idea, which implies that the original must exist in the drawing itself, as the conceptualization has only the potential to become a fully functioning work. It may not be far off to suggest that each time the wall drawing is resurrected an original copy exists. In discussion with fellow PORT star Arcy Dougless about production, reproduction, and lifespan of LeWitt's drawings, Dougless noted that one of the key aspects of LeWitt's wall drawings accurately manifesting was the amount of tolerance in mark he allowed its producers. Because LeWitt used the hands of others to realize his ideas, he was forced to decide what kind of tolerances he would allow. There was a period early in his career where he was admittedly over-optimistic about who could execute his ideas, and he was ultimately forced to reserve the production of his concepts to qualified draftsmen. Currently, the Sol LeWitt Foundation oversees the production of wall drawings, employing a team of artists who have received specific training in their execution.  Nobuto Suga wiping white crayon off his straight edge What Dougless was unearthing is the idea of permanence. Let us take the example of a copy machine. Instead of using a master copy to duplicate our work, we use each successive copy to make the next. Over time information will be lost due to imperfections in scanning and printing. Interestingly, LeWitt's wall drawings attempt to break this seemingly natural phenomenon of information degradation by embracing the forces that decay the original. LeWitt understood that people would always have slightly different inclinations as to how they make marks. His solution was to create a culture surrounding the production of his drawings infusing core thought processes that could be passed down through generations. Nobuto Suga is living evidence that the culture has been preserved, having learned his techniques from an artist who worked directly with Sol LeWitt.  Sol LeWitt's diagram for Wall Drawing #304 The ephemeral nature of the wall drawings' existence eschews a plethora of questions about authorship and ownership. Most would agree that Wall Drawing #304, even after having been completely drawn by Nobuto and Aaron, is still a Sol LeWitt. Yet LeWitt will never see Wall Drawing #304 as it is presented at the Portland Art Museum, and never knew of its existence in the first place. Truly this work could not be made without an entire team of people carrying LeWitt's legacy making each member as integral as LeWitt himself in the realization of the this particular work. Much in the vein of Duchamp's fabrications, LeWitt not only relied on others fashioning his ideas, he created work that was empowered by its delegation. He used a system that was straightforward and honest yet devoid of personal biases. His wall drawings foretold the integration of architecture, design, and art, while his conceptual applications begat an entire movement. What I will cherish most about LeWitt though, is his inherent inclusiveness. His ability to welcome people, be it through accessible subject matter or the physical production of his ideas, unifies the art world and the general public, two communities that are all too often separated by a lack of faith in each other. Posted by Jascha Owens on August 01, 2010 at 15:40 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |