|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Kertesz and Waselchuk exhibitions Though this August has been littered with weakish summer group shows two excellent

solo photography exhibitions next door to one another should not be missed, it is

their last weekend. At Charles Hartman Fine Art there is a fantastic museum level

exhibition spanning the entire career of master

photographer Andre Kertesz. Next door at Blue Sky Gallery it is the sobering

prison hospice care documentation of Lori Waselchuk.

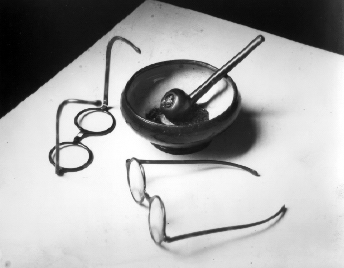

Andre Kertesz Washington Square, Winter (1966) At Charles Hartman the roughly chronological display covers classic Kertesz images like Lovers (1915) taken in Budapest to the iconic Mondrain's Glasses and Pipe (1926) from his Paris years to the fantastic Washington Square, Winter (1966) Taken in New York City. Kertesz is a master of geometric composition as Mondrian's Glasses and Pipe demonstrates with its asymmetrical table corner forming a tense pyramid on which the ascetic circles of the bowl, pipe and glasses rest in a seemingly offhand repose. Those three elements form another implied triadic form that along with the table makes a diamond referring to some of Mondrian's own paintings.  Mondrian's Glasses and Pipe (1926)

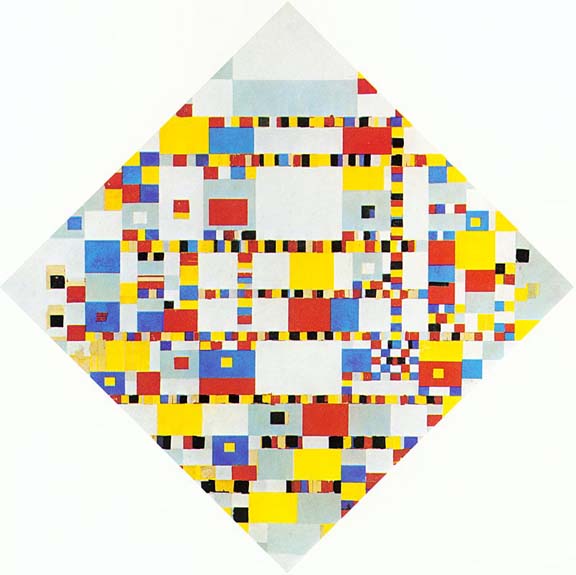

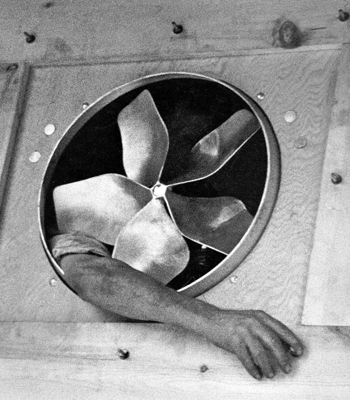

Victory Boogie-Woogie 1943-44 Piet Mondrian The image of Mondrian's glasses is so poetically deft and nonchalantly tense that it had to be taken by someone with a very intimate sense of Mondrian and his world as Kertesz was. Arguably, Kertesz's image is a portrait of Mondrian through his personal effects, which channels the a sense of the contemplation the master painter must have apprehended his own works with. Somehow Kertesz has captured the artist in his studio looking upon the tabla rasa of a primed canvas, except it's not... it's furniture and the painter's proxy possessions making the portrait way more telling than a can filled with Mondrian's brushes. It's as if Kertesz allows us to see a blank white surface in a way similar to Mondrian did. Also from 1926, in Satiric Dancer the photographer's model pantomimes a now classic Matisse showing even more of the inter Parisian artist humor on display in Mondrian's Glasses and Pipe. To the contemporary viewer these images seem historic and nostalgic but at the time they were taken they were cutting edge facets of modern life, full of the wit and humor of the age. It stands as a celebratory act or toast rather than a form of veneration. To view this image I feel like I just had a glass of red wine with both Matisse and Kertesz and 10 of their other friends. Similarly Dubo, Dubon, Dubonnett shows a witty Parisian street scene of a street bench, an advertisement with a man in a top hat and an ad for liquid refreshment. The witty play on words reveals the gritty daytime Parisian street life pairing it with a promise of night life and the intermingling with the well to do. It's the democracy of the intermixing classes that is modern here, though we take it completely for granted in America today. Back in 1926 it was all very new... writers like the classic Parisian prowler Charles Baudelaire knew these scenes well and Art historian T.J. Clark has made this bourgeois/bohemian intermingling the subject of his most famous book, The Painter of Modern Life... except of course Kertesz is a photographer and it's photography's ability to document these street scenes that pushed the Impressionists, Fauvists, Orphists and Cubists into ever more removed visual topographies while photography soaked up the allegorical light of the moment... a more mechanical process in a more mechanical age.  Arm in Ventilator (1937) Images like Roof Tops, Tiles 1927 and Arm in Ventilator showcase the loaded allegorical and compositional panache of earlier images such as Mondrian's glasses with a more anonymous mechanical ennui apropos of the late 30's with Europe moving steadilly towards all out war. By the time we see Lost Cloud from 1937 we have Kertesz living as a European exile in New York City and the cloud might as well be his own restless wandering soul. It's also a fantastic flattening of the depth of field somehow making the cloud seem as near as the building.  Lost Cloud (1937) By the time we see the witty Homing Ship, New York from 1944 we sense Kertesz feels much more at home in his new home. In fact, his compositions seem to take on a starker clarity, a logical consequence of the much starker rectangles that make up that new world city's grid. This geometric acuity only grew bolder with time as my two favorite prints in the show illustrate; Washington square, Winter (1966) and Martinique (1972). Washington Square, Winter is a simply stunning photo of Washington Square from one of the NYU buildings that surround it. I wonder if Kertesz saw the patterns on the ground first then sought out the appropriate vantage or if he simply caught a glimpse by accident from a lucky window. Something tells me this view was no accident with Kertesz waiting years just for the right dusting of snow with moderate traffic. The net result reminds me of aboriginal dreamings from which the earth bound painters compose the world as if they were floating above the earth. For practical reasons It has the same charm as looking at an ant farm experiment, seeing all of the passageways and routes created for practical concerns that also work as art.  Martinique (1972) Martinique (1972)

Martinique is by far the most mysterious and geometric of all of the compositions and Im glad the Portland Art Museum already has one in its collection. For me it reminds me of the Lost Cloud and Roof Top, Tiles with the same proxied abstraction and compositional strength of Mondrian's Glasses and Pipe.

Lori Waselchuck's "Grace Before Dying" series Next door at Blue Sky Gallery (a.k.a. The Oregon Center for the Photographic Arts) Lori Waselchuk's "Grace Before Dying" series is beyond powerful as a coherent exhibition documenting the prisoner-run hospice program at Angola State Penitentiary a maximum-security prison in Louisiana. According to the exhibition text, “more than 85% of the 5,100 inmates imprisoned at Angola are expected to expire there and until the hospice program was created in 1998, prisoners died mostly alone in the prison hospital.” The hospice program may not defray the inevitable but it does induce a certain crucial human dignity. Waselchuk's photos are sober and heartbreaking and the image of one inmate whose socks and pillow are labeled Ghost in magic marker are incredibly tragic-comic. Gallows humor indeed... fact is, inmates serving out life sentences are essentially ghosts already and there is something existentially poetic about seizing upon the irony. Also, according to the (in this case important) exhibition text now, “when a terminally ill inmate is too sick to live among the general prison population, he is transferred to the hospice ward. Here, inmate volunteers, most of whom are serving life sentences themselves, try to keep him as comfortable as possible. During the last days of the patient’s life, the hospice staff begins a 24-hour vigil.” These vigils displayed in wide format high contrast black and white images have an incredible earth bound quality and read counterclockwise around the room take us from ghost to pall bearers to hearse and cemetery. Waselchuk's three year project was handled with extreme dignity and each image like the subject matter itself has an air of compositional inevitability. We don't sense a virtuoso at work here, Waselchuck instead flattens and humanizes the experience with a restrained lack of drama, as if her shutter button were simply being pressed by the hand of fate.  Pall Bearers What is remarkable here is that something so invisible to the general populace is succinctly presented with clarity and reinserted into the human record. We all encounter death daily, but inmates and the terminally ill experience it in such a profoundly compressed way that everyone who encounters their situation partakes in a profoundly reflexive communal existential experience. There is something beyond compelling about the human will to live. It isn’t pity either. Instead, it's our strongest form of empathy... an interest in the human will. Truly it is why we watch boxers fight and daredevils tempt fate, why we love it when babies or dates eat and old people act younger than we allow ourselves to... and yes we watch those with a death sentence of some kind fill out the hours with a mixture of awe and horror because it's a compulsion as powerful and consuming as our first breath. See these two shows in the Desoto building (between NW Couch and Davis at NW 8th ave.) if you want to contemplate the human experience in its most distilled form. Posted by Jeff Jahn on August 27, 2010 at 9:17 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |