|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Donald Judd... now Exhibition essay: Donald Judd, White Box at The University of Oregon Portland by Jeff Jahn

Suddenly and without the prompt of a recent high profile major museum exhibition in the United States, the work of the preeminent artist Donald Judd (1928-1994) has enjoyed renewed interest amongst the most recent generations of artists. Reactions to his influence are everywhere in art, architecture and design schools today. So much so that if a clean box that avoids illusion or attention getting details by being well-made of metal, Plexiglas or douglas fir is present, so is Judd's legacy. The pity is that ubiquity extends a pervasively superficial understanding of Judd.

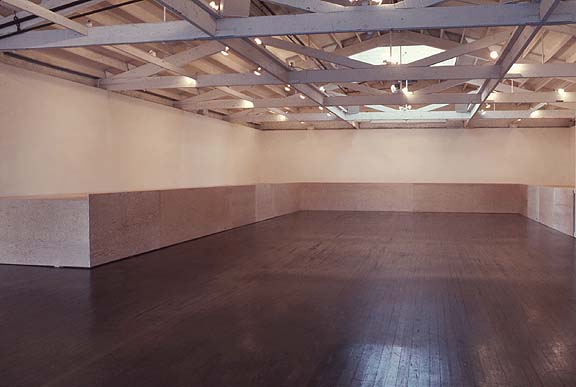

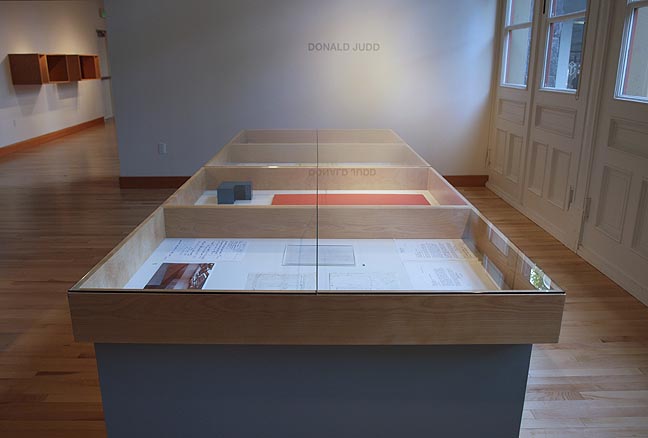

Judd Art (c) Judd Foundation. Licensed by VAGA, NYC (photo: Jeff Jahn) In the support of the conference Donald Judd Delegated Fabrication this exhibition is the first ever to look at Judd's process by paring major works with drawings by Judd for fabricators, production drawings by fabricators and other ephemera. The documentary film by Chris Felver provides context for Marfa and Spring Street and the issues Judd himself saw as key. On display, the disparity of detail between Judd's drawings for fabricators and those of the fabricators themselves show just how much delegation Judd engaged in. What's more Judd was a remarkably consistent artistic force who delegated the fabrication of his work to get control over it. Not only did he gain superior production values that removed details (destructive to his noncompositional art), the practice allowed a more detached appreciation of the whole's result. It is humanly impossible to craft something to such high tolerances as a Donald Judd piece without becoming sentimentally attached to the choices and labor that went into making it and Judd shrewdly removed himself so he could see the piece not the work put into it.  Donald Judd, Untitled, PCVA (1974 )Judd Art (c) Judd Foundation. Licensed by VAGA, NYC (photo: Maryanne Caruthers) One revelation from the conference was that the Judd exhibition at the Portland Center for the Visual Arts in 1974 was the only time Judd used volunteers for fabrication. Yet Judd was pleased enough with the result that he noted it in his final essay Some aspects of color in general and red and black in particular. As his largest and most radical use of a whole room at the time the "Portland piece" showed how Judd gave up minute level control to get greater experimental control over his work. Also, I propose some terminology for Judd's fabrication. During the conference Peter Ballantine described Judd's philosophical makeup as an "empiricist" or even "pragmatist" that tended to be, "more pervasive than deep." Similarly, by delegating fabrication Judd could empirically appreciate the end result with fewer (pragmatic) entanglements and in a way this leads a more sustained and consistent approach. This is much like a scientist waiting for lab results from his technicians. That fabrication process also parallels Judd's use of manifold spatial constructions with no obvious beginning or end and a matrix through which the viewer (or Judd) could perceive a little slice of the universe straining through a structure. I propose that the term "manifold" which Judd used for his work applies to his manifold use of fabricators like; Bernstein Bros., Jose Otero, the volunteers at the PCVA or Peter Ballantine as well. All had key roles to play and specialized in specific materials, but other fabricators could have done the job. Despite all of this information one local professor (educated in the late 80's) still wanted to understand, "why all this interest," from her students? The answer is simple; no artist in the history of art has exerted greater control over the ideal presentation, production and discussion of their own work in the context of their peers. It's a function of integrity and in the case of Judd it is pervasive. In a time of relentless uncertainty, Judd has become a kind of Planck's constant or a benchmark of American achievement and integrity in art. Perhaps this new generation of artists note Judd's ability to do an end run around institutionalization despite being the subject of numerous writings and major retrospectives at the Whitney (1968, 1988) and most recently the Tate (2004).

Judd Art (c) Judd Foundation. Licensed by VAGA, NYC (photo: Jeff Jahn) As to this exhibition, it is particularly fitting that the gallery resides in a cast iron building, which Judd favored (another manifold form). Because Judd's work isn't about the object itself, but rather the experience of space this makes the exhibition feel quite dissimilar to a museum exhibition or a commercial gallery setting. Lastly, it is a rare privilege for Portland to share and learn from curator Peter Ballantine's unique 42 years of expertise as a Judd fabricator, curator and friend. Primary sources, such as Judd's fabricators are of the utmost historical significance as history is rapidly erasing their stories. This exhibition is distinguished through his involvement and we hope it spurs further meaningful exploration. This exhibition supported in part by the generosity of: Anonymous, Anthony Meier Fine Arts, Elizabeth Leach Gallery, Judd Foundation, Miller-Meigs Collection, Jarl Mohn, Laura Paulson, Peder Bonnier Inc, Regional Arts and Culture Council, Bonnie Serkin and Will Emory, Irving Stenn, Weiden + Kennedy, Van de Weghe Fine Art. Exhibition loans: Margo Leavin Gallery, Jarl Mohn, Miller Meigs Collection, Paula Cooper Gallery, Peter Ballantine, Portland Art Museum (PCVA archives) Special presenting support by: Karl Burkheimer, Paige Saez and PORT Posted by Jeff Jahn on May 06, 2010 at 13:12 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |