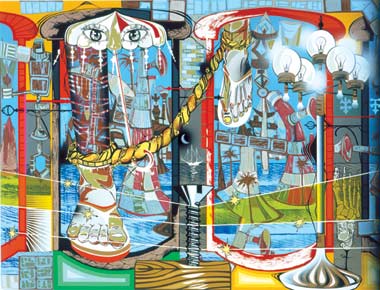

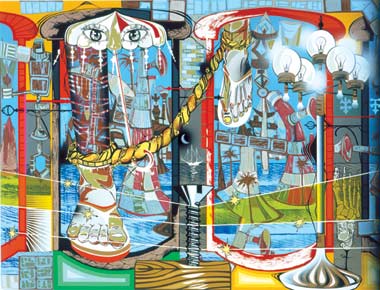

Untitled 2002, Lari Pittman

The most recent, long running show at the Portland Art Museum, Disquieted, is an exhibition rife with contradiction and conundrum. Opalescent and beefy with the reputation of its artists, Disquieted boasts an exhibition to impress and seduce. Its mission statement claims to bring together works that challenge and question social convention and social practice, works that imply a perturbed, dissatisfied state of apprehension somehow caused by the experience of a contemporary existence. While this goal is lofty and seemingly relevant, its bar is high, and its reality is an atmosphere that is raw and piercingly specific; to create the ambiance of a public unnerve, a state so tangible and so pervasive and which runs through the thread of everyday existence is ambitious, gripping. This is not an academic goal; it is an existential one, and while Disquieted touches upon this jumpy nerve occasionally, as a whole it seems more to want to sit right next to it. When perusing the roster of artists in the show, it seems a more apropos, accomplished bunch could not have been gathered to create such an aura, which is why the show is puzzling in its sporadic success. To understand this phenomena calls for a gentle yet thorough dissection.

"In the Midst of Dreams" 2009, Jaume Plensa

The first piece encountered is the installation in the foyer, "In the Midst of Dreams", by the artist Jaume Plensa. Three enormous female heads sleep facing one another, emanating an ethereal glow. White stones surround these monoliths and act as their shared, unifying body. Upon closer examination, it becomes clear that each girl represents a different ethnicity. Random words denoting suffering, pain, and ill will ornament their sleeping faces and define the piece as some sort of colorless oracle. As they sleep, they seem ready to be asked a question, ready to perform, as the subjects of their dreams stream around their young faces. The choices of the words seem somewhat haphazard and pandemic?, and are reminiscent of sinus medication commercials. The experience of this piece is somewhat hampered by the limited space of the museum foyer, yet coincidentally draws attention to the eloquence of its design (particularly the ceiling, which appears as an illusory asymmetrical angle yet is not). It is a dichotomous flux of emotions that perhaps is meant to produce anxiety, which it does, yet not in the way it might intend. The transmission falls short as the intentions of the artist do not seem to mingle with the experience of the viewer. This ambiguity can lead to groping for specifics granted by the piece's visual cues: Should we assume the presence of bodies beneath the stones? Should the viewer assume each head's words are directed at the other head at the viewer? Is this a piece about racial tension? Everyday life tension plus racial tension? A proverbial reference about throwing stones? In this way, the artist condescends his audience somewhat in combining occasionally shallow ingredients in what could have been a rather surreal piece. The words are unnecessary.

Disquieted continues its first half (divided unfortunately, but necessarily by the architecture of the museum and thus coincidentally visually, mentally) behind Jaume Plensa's introductory piece. Entering into that first room, the body politic immediately becomes the issue at hand as catalytic platform. Barbara Kruger's piece, "Your Body is a Battleground" (1989) is wonderful to see, but somewhat gimmicky in this context. The body becomes an "issue" section of the general mission of the state of our general societal unrest. This is a condescension to the viewer, expecting that dispersed throughout the show, this would not be, could not be understood. The room does not need Kruger's text to introduce its content. Her piece marks the declaration of some of the most recent topics of social unrest, yet placed here, the piece is pigeonholed. This is the problem with much of this exhibition; the constructed context of viewing these pieces leads to the halting of their inherent potential.

Charles Ray's pieces are screaming gendered totems, multi layered and weary under the weight of their roles, under the weight of our assumptions. They embody this politic wordlessly while asking questions at the same time. An eight foot woman in a fuchsia powersuit with her hands on her hips will greet you at the forefront with her giant smile between her mannequin ambition and our stereotype, unapologetic in her unadulterated power lusty stance, unapologetic of her existence, despite its reaction. What do we think about her? Do we know her? Do we think we know her? Is she the totemic foil in body (and spirit) to the naked male form behind her, whose lithe, gentle stance almost suggests expression? Or do we make assumptions from their physicality about these mannequins, and thus the world? The male form behind her counters her existential aggression. His submissive countenance is marked by the realistic rendering of his flaccid, yet visually prominent sex, swarthy against such genteel, fabricated beauty, historically counter to the visual ideals of masculinity. Ray presents us with our own assumptions to face and understand.

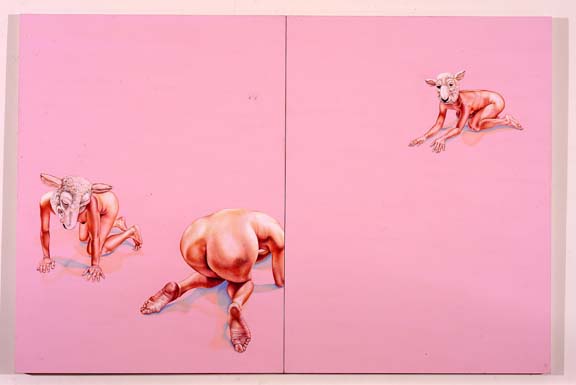

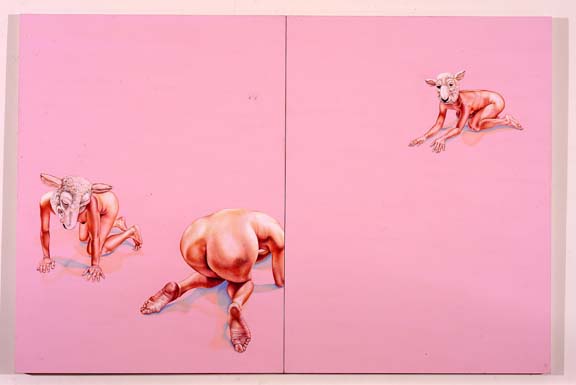

Su-En Wong's piece here is a strange addition. Seen usually on continuous display in the contemporary wing of the museum, it has been placed as a part of this show somewhat randomly, yet is also quite indicative of much of the show; while Wong's work is perfect for the exhibition, this particular painting is not the most effective example of her work. The logistical ease of including this piece is understandable, yet including it weakens both the painting and show. This is an undercurrent running through the holes in Disquieted; many of the artists' works are poor representations of what they do. The inclusion of Wong's painting feels as if either there wasn't enough work, or that the Portland Art Museum felt the need to include a piece from its own collection.

"Baby Pink Painting with Three Girls" 2000, Su-en Wong

Doug Aitken's piece, "FREE" 2009 looms lavishly in the center of the room, cinematic and grandiose in its depiction of a decaying casino. What is free? , we ask him. Destruction? Chaos? Freedom? Because it isn't, he seems to also say. This piece is lovely and poignant, yet juts up against the body politic to dissect the room. Moving through the space of the museum, John Baldessari and Daniel Richter's pieces sit next to one another in a bizarre juxtaposition. While both visually riveting, Baldessari's metaphysical, humorous compositions placed next to Richter's anarchy in fluorescent relief is a radical and perhaps somewhat awkward jump. While both artists' sensibilities and constitutions advocate conversation, both visually and ideologically, due to their context, they seem an island of something that could be interesting but becomes chopped up in the arrangement of the other pieces. In many ways, a creepier show would be all of Richter's work, or the disquieted of Richter. These sentiments are difficult to pinpoint, because these works, considered alone, do fit the definition of the exhibition's mission statement. Murakami's paintings are sexy, cartooned renditions of the underlying forces, beautiful, menacing, and chaotic. Yet Sue Williams', Wangechi Mutu's, and Paul McCarthy's pieces bring back the ideas of the body. At this point in the exhibit, the genitalia theme begins to become sort of hackneyed. The choice of the McCarthy piece, "Brancusi Tree (Gold)" is particularly baffling, as it seems perhaps the tamest McCarthy piece that may exist. The corner its placed in further undercuts its possible emphasis; one would think such a piece of McCarthy's would want to be in the center of a room somewhere, resplendent and horrific in all it's golden anal glory. The Crewdson and Emin pieces around it fortunately undercut some of its shrewd but crass satire.

"Brancusi Tree Gold" 2009, Paul McCarthy<

Moving onto the second floor of the exhibition, one feels an ideological shift mimicked in the architecture. The soundtrack of Shirin Neshat's film, "Posessed" pervades the atmosphere and adds an eerie ambience to the air around these pieces. Ellen Gallagher, Glenn Ligon, and Sanford Bigger's pieces are grouped together in a racial political spectrum that mimicks the body politic below them, once again visually undermining the possibility of the pieces and the intelligence of the viewer. These are some of the most powerful, most interesting works in the show, and I cannot help but wish they were interspersed with their peers for a more powerful visual impact, as opposed to grouping together the artists whose work concentrates on race here, the artists who discuss gender there, the anarchists over there, and the ones who operate under their own personal mythology here.

One of the most actually disquieting pieces in the show is Jan Tichy's piece, "1391". On every level, it operates as a silent and eerie aspect of something in our current culture that is very real. It is as visually stunning as it is subtle: an open political nerve in white. It is as effective as a bullet. The viewer leaves this tiny piece with chills. Carrol Dunham's painting on the wall behind it mimicks 1391's political reality in a more personal anecdote, and Ron Mueck's figures illustrate anxiety in a skin that is as tangible as our own. Shirin Neshat's film is beautifully shot yet a bit too constructed, as the lead actress does not seem to be a part of the surrounding community, once again, not one of this very brilliant artist's strongest pieces.

1391, 2007, Jan Tichy

Disquieted is an exhibition of lofty ambition and meaty work whose vision is fractured by the lack of its editing. Seduced by big names, it forgets to be critical enough of what one can actually see. While absolutely luxurious to see these incredible artists of such varied practice and geography in Portland, their respective representations within this show are not as accurate as they could be. It is an exhibition of hits and misses, of crescendos and plateaus.

This was by far the best contemporary exhibition at PAM since "Let's Entertain" a few years ago. It is great to see new work by the likes of Robert Longo and others!

Mike, I agree... the best group show at PAM since Let's Entertain. In many ways a group show invites "uneveness" and I thought the Suen Wong fit perfectly where it was. I agree the Baldessari's placemment made very little sense.

Overall I would have limited the choices to the past decade... the inclusion of all the early 90's identity politics though completely relevant made the show a little more diffuse (because its inherently nostalgic).

I believe Including pieces from the collection deepens visitor's engagement with the museum and gives a little insight into Bruce's selections for the collection over the past few years. That alone is valuable.

All that said I hunger for an in depth solo show of a major artist and couldn't be happier that PAM is finally adressing Rothko with a show in 2012. There's some local business there to be done since Rothko is Portland's most famous son.

See this show...

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)