|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Hannah B. Higgins: An Interview of Primariness  Hannah Higgins Hannah B. Higgins is an Associate Professor at University of Illinois at Chicago. She is also the daughter of the Fluxus artists Alison Knowles and Dick Higgins and noted author of Fluxus Experience, and will be lecturing in tandem with Gestures of Resistance this Thursday at 6:30 pm at PNCA. > Is there a right or better way to experience "primary phenomena or ecological information?" The point of a primary information orientation is not that there is one way or a better way to access it. Walter Ong's writing on sense ratios and hierarchies demonstrates that the ranking of sensations is cultural (the primacy and isolation of vision, the low rank of smell, for instance, reflecting western values). So sensation is always filtered through values and value systems. The acculturated nature of the systems, however, is best explored when we attempt to access information in a primary way. Usually we fail. However, in the attempt things become strange, exposed as social mandates. In this negotiation, information becomes ecological in the connecting sense. In a multicultural society, this means there isn't one way or a better way to approach ecological experiences of information, though there may be ways that tend to obstruct the attempt instead of aid it. Overly fixed interpretation and systems-based analysis of aesthetic experiences tend are to my mind less useful than, say, thick description or kinds of writing or understanding that trigger an empathic/involved response.

> Can writing/language be a form of primary information? Of course. See above. Primariness is attitudinal. > Would you say that a primary focus on secondary information is hurting society? Yes. It is harder and harder to think for ourselves. The point being that it is harder and harder to have the grounding sensation of thinking for ourselves. > Why is it important to you to have built such strong lines between other arts and Fluxus? Art making doesn't happen in isolation. Rather, artists solve sensory, intellectual and formal problems relationally. There is always an imagined audience even if it's the artist him/herself. As a result, the primariness of Fluxus, for example, offers something more generally to our understanding of the arts at the time. The art sensibilities of the 1960s were myriad and happening on top of each other. We understand them all better when we approach them both as unique but also as related tendencies. > Do values of deconstruction aid primary experience? Yes and no. Deconstruction at its best makes things strange in ways that are useful as access points for primary experience. But the unnecessarily complicated writing systems of deconstruction sometimes create a deterministic, endlessly self referential, meta object (which gets in the way of primariness). Also, in the 1980s and 1990s people became evangelized with deconstructive practices so much so that we collectively went down the rabbit hole, but never landed anywhere. No wonderland. No red queen. No caterpillar. Just a lot of falling. But I may be referring to the cartoon version of deconstruction as an endlessly shifting semiotic lens. I was rereading Derrida's Truth in Pointing recently and it was better than I remembered.

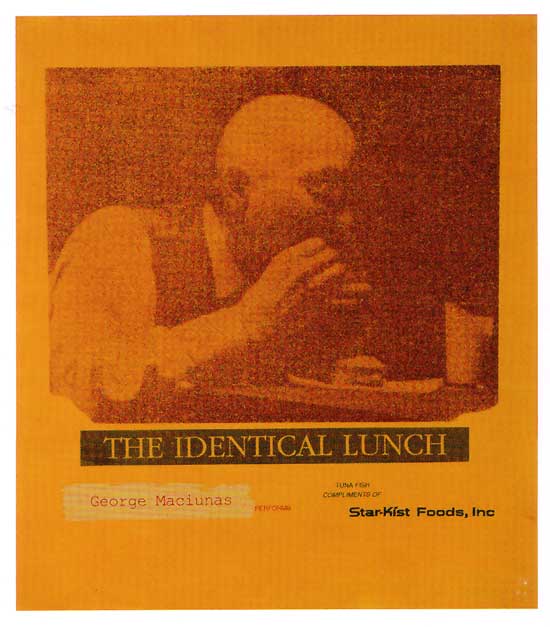

Alison Knowles, The Identical Lunch [2nd Edition], 1973/93 silk-screens in cadmium > Is paradox an essential element for fluxus? That depends on the artist and the audience. Some artists are very effective with paradox (George Maciunas, Bob Watts and Eric Anderson come to mind), while others don't seem very interested in paradox at all (Phillip Corner, Jackson MacLow, Alison Knowles). So one couldn't say essential, but repeating maybe and perhaps essential if we take Fluxus as a single, complex object. > Is "failure of imagination" a phenomenon of modern/contemporary societies or something all peoples have to work at or deal with? Creativity is how people move from the known to the unknown. We see it both in the basic problem solving that leads to new technologies and also in the ways people create the narratives that explain their worlds or help them to imagine new ones. Cultures wither when creativity becomes obsolescent. This happens either by overt oppression (as in repressive political regimes) or when a sense develops that 'it's all been done before,' that social or material problems have already been (successfully or unsuccessfully) addressed. Our information overload society is at risk for the kind of acquiescent attitude. But of course the world is ever changing, so in fact nothing's been truly tried before. Ever. > Did you ever get to meet John Dewy or John Cage? Cage was part of the NY Micological Society that my parents were involved with, so I have early memories of mushroom hunting with him and he came regularly to dinner and sometimes holidays like Thanksgiving or Christmas. > How do/did your parent's influences affect your thinking about fluxus? My parents were very close to Cage, so his presence in our house and my knowledge that he'd been Dick's teacher at the new school meant that I tended to see things through the lens of the social scene framed by experimental music. Jim Tenney, who did electronic and computer music, Malcolm Goldstein (the violinist) and Pauline Oliveros were also close family friends and there were noise music and electronic music events at Phil Niblock's loft, where we'd see people we knew. I didn't particularly like the music and couldn't understand it, but I loved its people. As a result, I saw the music scene as primarily social and experienced Fluxus as a piece of that greater, experimental world. It wasn't until I got to graduate school and started reading about neo-avant-gardes and Dada and angry anti-art that I understood what the world believed about these artists. There was no resemblance. > How did researching Fluxus affect your nostalgic memories of childhood events? Not much. My memories were not nostalgic except that I enjoyed the other flux kids a lot. We'd hang out backstage or in the wings somewhere and have our own experiences. We were not very interested in what was going on in front of the audience. That came later. > How was your fathers relationship to George Maciunas? In the end they resolved differences that cropped up when Dick decided to publish his and his friends' work that was in The Something Else Press. There was initially some rivalry, since Maciunas wanted to control what could be published, performed and exhibited as Fluxus. Since no one ever elected him to the position and people pretty much went on with their own stuff, it got pretty silly pretty fast. In the end there was a solid community of active people making art and I remember visiting George as he was dying of pancreatic cancer and the feeling between Dick and George was very warm. > Do you have any fluxus work? Less than you'd think. Dick went bankrupt in 1975 and we lost everything (house included). As a result, any Fluxus objects he had, and most of The Something Else Press books were sold off to pay bills. He died penniless. There was German collector, Hermann Brown, though, who began giving me duplicates from his collection in the middle 1990s, so I have a few of the old kits and two of George Brecht's Water Yams thanks to Hermann. > Thank you Hannah for sharing these memories with us. Posted by Alex Rauch on April 20, 2010 at 9:06 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |