|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Leon Golub at PAM The work of Leon Golub at the Portland

Art Museum is an interesting introduction to his raw and fearless contributions

to modern painting. The show, composed mostly of portraiture made during the 70's

as well as a larger sans-stretcher painting, typical of his most recognized style,

resides on the bottommost floor of the Jubitz Center for Modern and Contemporary

Art.

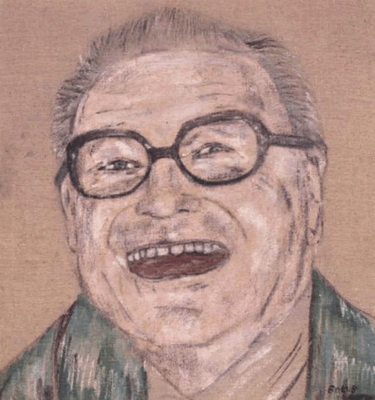

Francisco Franco (1975), 1976, Acrylic on linen, 20x17 in The Broad Art Foundation, Santa Monica Golub's work seems well suited as the ambassador of postmodern and contemporary concepts, with its classical command of the figure and raw use of materials. His paintings are unassuming in a strange way. Certainly the figures and the investigations of power relations resonate outwardly but the paint itself rests quite silently. As nearly a bland porridge of line and canvas stained with paint, Golub's works rely on neither intricacy nor grandiose gesture, but opt rather to produce a pure and unobstructed image. The result is a fearless reflection of humanity unto itself. Golub cultivated such honesty through his beliefs in art an institution for social change. During a time of minimalism and conceptual beliefs Golub stuck to his guns and continued his path towards figurative abstraction and art with a purpose beyond the institution. Though he has been criticized for presenting too simplistic a relationship between the oppressed and the oppressor, I found his work to hold depth in that regard as well as others.  Merceneries I, 1976, Acrylic on linen,116x186 1/2 in The Broad Art Foundation, Santa Monica Mercenaries I demands emotional complacency from its viewer. One is at first repulsed by the image of a burnt and crippled man tethered to a pole while dragged by a pair of American soldiers. Somewhere after rejection and understanding one begins to feel the creep of acceptance. It is here that Golub taps into the subconscious of his viewer. Years of exposure to similar images from the media begin to make their way forward, disrupting the brutality of the image and instead forcing an irrational acceptance of injustice. One starts to notice the subtleties of the painting, such as the gaudy smirk of the white soldier or the trophy like presentation of their victim, leading the viewer back towards a pure rejection of the image. The audience is left uncomfortably in this limbo, alternating between states of association by justification with the oppressor and the oppressed.  Goya, Duel With Cudgels It is not surprising that Golub's work brings to mind the famous "Black Paintings" of Goya. The haunting imagery in Golub's work harks to Goya's series while the subjects of both painters' flirt with the idea of senseless human violence. I am especially reminded of Goya's painting depicting two men sunk in sand while striking each other with sticks. Duel with Cudgels is cited as presenting the futility of a civil war in Spain, each side represented by a man with a club. Both artists confront us with our inner demons, especially the fickle nature of human compassion. Through the "Black Paintings" and Golub's works we are exposed to the possibilities of our own grotesque nature gone unchecked. I found the depth of Mercenaries I to trump that of the other works in the show. Delicate as the portraits were handled I did not find similar confliction in my relationship to the totalitarian figures. These portraits successfully present a view of recent despots outside the context of political agenda and media influence. Indeed they almost become the profiles of indiscriminate people that may have been painted by any number of street artists with Golub's handling of materials. Furthermore, it may even have been the intent of Golub's to recontextualize these figures off their pedestals, but their placement on the walls of the museum venerates them nonetheless. The audience still experiences the similarities and associations that would occur had the images been on a newspaper or a TV set.  Portrait of Nelson Rockefeller, 1976, Acrylic on linen 18x17 in The Broad Art Foundation, Santa Monica Of all the portraits I found the series of Nelson Rockefeller to be the most successful. Golub captures the entanglement of image and its audience through the use of chronology quite convincingly. The series lives through the trials of a young man gleaming with idealistic fantasies to a Rockefeller tarnished and cracked by the unforgiving nature of politics. Though we are presented simply with a man aging, the process yields an inventory of media driven associations from foreign policy to art patronage. Exposed to this process of association we confront the narrative written by historians and politicians enjoying instead a sense of camaraderie through the frailty of human life. Golub's is a language that speaks directly. His characters teeter on the edge of being commonplace though they reside in a story far from the average viewers life. Golub relies heavily on his audience's exposure to the media and uses this relationship to create conflict and tension in his work. The straightforward and unforgiving attitude leaves a bitter taste in ones mouth, knowing that the atrocities committed by Golub's figures are of a human nature set loose by the inevitable imbalances of power. Posted by Jascha Owens on February 23, 2010 at 9:45 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |