|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

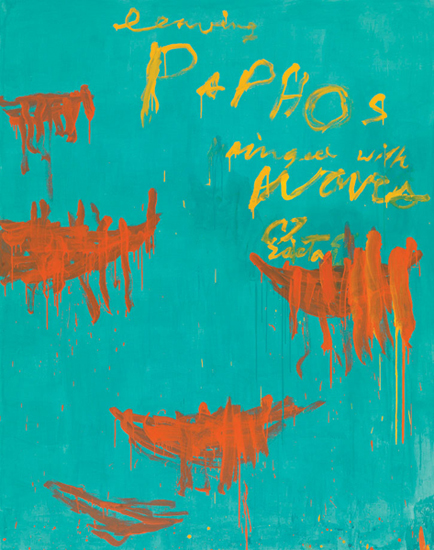

Cy Twombly  Cy Twombly, "Leaving Paphos Ringed With Waves III," 2009 One of the first things I notice when I am lucky enough to be able to stand in front of a work by Cy Twombly is the material. The paint is allowed to find a life of its own. Very few painters use the natural character of the material with the same freedom in the way that he does. It is given enough space so that it is fully allowed to express its own possibility. Twombly doesn't need to change or challenge that basic possibility; he is able to use it to forge his own language. His work exists between the tension of the material and the image. Ancient sculpture was based on searching for ways of turning marble into flesh. Later, painters devoted their lives to discovering ways of converting matter into light centuries before Einstein. While the tension between image and material that exists in Twombly's work is not new, the fusion and the ambiguity of his approach is uniquely contemporary. When Twombly creates a painting, he is not interested in representing or illustrating anything. His work attempts to literally recreate emotions, poems, historical battles, figures and feeling. These are spaces full of feelings, heroes and poets. He wants to recreate it all right in front of you and bring you into the process while he does it. He wants us to intensely feel all of the emotions and contradictions that are inherently part of being human. In fact, I wonder if he considers anything that is presented as only one thing to be intrinsically false and inherently unreal. There is no life without death. There is no love without loss. There is no glory without transience. His is a work of suggestions, intuitions, flashes, advances and logical leaps. Just as there are two sides of everything in Twombly's work, there are two sides to his process as well. For a work that is all about emotion and suggestion, Twombly's process is extremely rational and clear. There is a precision in his work that is surprisingly classical. Before he begins a painting, one gets the sense that he knows exactly what he is interested in at that moment and the subject he is trying to communicate in a given work. He might not have any idea what the final form of the painting will be, but he understands exactly the intention of the painting. His process is the opposite of DeKooning who would cover a canvas in paint, scrape it all off and then begin again until the form of the painting slowly revealed itself over time. Twombly on the other hand knows exactly what he wants, but he needs to collaborate with the materials to get it. The critical difference between illustration and re-creation is time. If you are illustrating an idea, it exists perfectly frozen in one moment forever. It never changes. It never grows. It never dies. It is never alive. I think that illustrating anything is anathema to Twombly's work. When you are up close to one of his paintings, you will often see that that he makes a mark, that is then partially erased and sometimes a new mark might be placed directly over the old one. It makes you wonder if he did not like the first mark in some way. Perhaps it wasn't the exact the form that he needed to communicate the intention of the painting. As you begin to sit with the painting, you realize that even if the first mark was the best mark ever made in the entire history of the world, it was still going to get erased. Perhaps if it was really the best mark, it is going to get erased twice as fast. He is not interested in perfect form or perfect fidelity with either an inner or an outer world. His work is not about form, it is about life and life exists in time. The best way to bring time into the painting is by creating the work in time. Time can measured from one mark to the next or from one wash of color to the next. To obliterate any of these layers is to obliterate the time in which they exist. While the intention of the work is clear, the form of the works changes as the works grow in time. When we are fortunate enough to be around these paintings, we can participate in their life as well. We can watch fields of red paint become explosions of color in Spring, fireworks in July and maybe splatters of blood in Winter. In other works we might be along for the ride on a long sea voyage across the Mediterranean in ancient boats, sung to and about by great poets. The paintings are all of these things and none of them at the same time. The work is never one thing. That is what makes them so exhilarating. We are no longer passive viewers, but active participants in an extraordinary drama that unfolds in the work. Cy Twombly at the Portland Art Museum February 6, 2010 - May 16, 2010 Posted by Arcy Douglass on February 10, 2010 at 19:27 | Comments (7) Comments Arcy -- As I am reading your piece, you are suggesting that representational art is merely illustration -- I'm not sure that I'm right about that, but with provisional apologies I'm going to respond as though I am: "The paint is allowed to find a life of its own...he is able to use it to forge his own language...His work attempts to literally recreate emotions...His work exists between the tension of the material and the image...He wants us to intensely feel all of the emotions and contradictions that are inherently part of being human. In fact, I wonder if he considers anything that is presented as only one thing to be intrinsically false and inherently unreal...His is a work of suggestions, intuitions, flashes, advances and logical leaps...For a work that is all about emotion and suggestion, (his) process is extremely rational and clear..." For me, you might as well be describing Chardin. For me, engaging representational art is never so much about the thing illustrated as it is about our experience of it, which is why it has the effect of suggestion, of evocation, of MYSTERY, that is essential to successful art. It is true that some representational painting is mere illustration of an idea, and is therefore dead, but that is no less true of non-representational painting. It seems to me that you are not contrasting Twombly's approach with representational painting, but with bad painting. Posted by: rosenak Thanks for commenting on the post. I think that you make an excellent point and it is worth discussing. I agree that all great art has to a sense of mystery, although I might use different words to describe it. It is what compels to sit in front of a work long after we feel like we have carefully examined all of the details. That there is still something there to learn or to experience or maybe it is simply that it is front of a certain painting that strikes us the best place to be during certain period of time. Rather than using the word mystery though, I would rather say that it is the quality that makes a work compelling. I also think that whether a work is compelling or not is in direct proportion to the artist's ability to produce an uncanny resonance with the world beyond the work. Maybe Picasso said it best, art is the lie that tells the truth. When I am looking at work, am I thinking about the work or I am thinking about the artist? I think that the work is compelling when I can forget about the artist and concentrate on the work itself. If the artist never lets me get to the work, it is going to be a difficult experience. Chardin is an excellent painter and one of the few painters that is probably more obsessed with mortality than Twombly. When you are looking at his still lifes with the rotting meat, you are at once taken in by the beauty of the painting and repulsed by the subject matter. Of course, when you are confronted with death of any kind in a work, it often reminds us of our own mortality. Looking at Chardin is a complex experience, you are caught up in this world that he has created for you but the subject matter in the painting also immediately brings up all of these other issues that somehow become intertwined with your experience of the work. Chardin's obviously a great painter but like a lot of great painters he does not leave a lot of loose ends that the next generation of painters can pick up on. If someone starts painting rotting meat, they are almost immediately all of these associations with Chardin so isn't better to go paint with something else? DeKooning was obsessed with Chardin. If he could have traded the way he painted for Chardin's, he would have done it in a second. He talks about his admiration of Chardin at length in several interviews. But even DeKooning had to go find his own way, copying or imitating Chardin would have never been enough. Twombly lives in our world today. He is affected by the current events in the same way that we are. He is using the materials of today. Chardin's paintings as beautiful as they are belong to a time and a world that is not my own. It is not even a time that I could even pretend to understand why Chardin felt compelled to paint the way that he did. In that sense, it makes me an outsider when I am looking at his work. With Twombly it is different. Not better but just different. This bring me to the last point. I understand that the difference between abstraction and representation is not made of a series of clear divisions but rather almost infinitesimal gradation. Twombly is a good example about how it can be difficult to determine one from the other. Still, looking at abstract art is fundamentally different than looking at representational art. In Chardin, if I am looking at meat, I am thinking about the body and life and death and all of these other related issues. Although the issues are probably profound it is ultimately a very narrow slice of all of possible experience. The best abstraction is not tied down to any one set of issues. Its only connotations are the ones that the viewer brings to the painting. The danger of abstraction is that it becomes only about its formal properties but I would say the best paintings really start to work when you are bored, or at least disinterested in their formal properties. Representational paintings are by definition mostly about what they are. The best abstract paintings are never about what they are. You couldn't say that the subject matter of an Agnes Martin painting are horizontal lines just as you could never say that a Reinhardt painting is about a virtuoso skill in the subtle gradations of black. Those are the tools and not the content. Not always, but in most representational paintings the image, the tool and the content are often one in the same. That is almost never true with abstraction. For me that is big difference. In Twombly's case, I think there is always a fundamental ambiguity between image and form that resists any single clear reading of not only a gesture but the work as a whole.

Posted by: Arcy "It is what compels to sit in front of a work long after we feel like we have carefully examined all of the details. That there is still something there to learn or to experience or maybe it is simply that it is front of a certain painting that strikes us the best place to be during certain period of time." Yes, this is a very good way to describe the effect we are talking about. A year or two ago I saw a show of paintings by Neo Rauch. I wandered in, glanced around, and thought, "Okay -- I get it: sort of a facile glib cartoony surrealism," but I kept looking and the more I looked the more I couldn't help looking, to the point where I had to call and apologize to a friend I was supposed to meet across town because every time I tried to leave the gallery the paintings pulled me back in. The more I looked, the more I understood how the paintings were put together, but the less it seemed that the limits of the paintings were within my grasp. I was transfixed -- a state where art IS something rather than ABOUT something. In other words the paintings were alive to me. We tend to have set ideas about what we understand least. The people who seem the most unknowable are the ones we know and love best. We are wired to order and limit; profound unknowing is beautiful because it's the state of being open to the world. All of the representational painting that I love works for me that way. It is the art of opening the world by bringing you to a state of unknowing through knowing. (I say this despite being incapable of explaining it because I believe there's a truth in there somewhere that someone might recognize even if this reads like a bunch of shit). That's why I use the word "mystery." "I also think that whether a work is compelling or not is in direct proportion to the artist's ability to produce an uncanny resonance with the world beyond the work." While it's true that representational and non-representational art are different -- they must be, as there is very little non-representational art that moves me -- I think that you and I are looking for the same thing; it's just that we are finding it in different places. .................................... "The best abstraction is not tied down to any one set of issues. Its only connotations are the ones that the viewer brings to the painting." I'd say this is true for representational work as well, but for your inclusion of "only". Unfortunately, people are too often encouraged to think that the value of art comes from capturing a specific "meaning" as if were a fixed and discrete thing planted by the artist to be extracted whole by the viewer (high school English, anyone?). This way of thinking, not the art itself, is what sometimes ties good representational art down. .................................... "Twombly lives in our world today. He is affected by the current events in the same way that we are. He is using the materials of today. Chardin's paintings as beautiful as they are belong to a time and a world that is not my own. It is not even a time that I could even pretend to understand why Chardin felt compelled to paint the way that he did. In that sense, it makes me an outsider when I am looking at his work. With Twombly it is different. Not better but just different." "Today" strikes me as arbitrary. If we don't mean it in the most literal sense -- February 12, 2010 -- how do we define it? In the context of this conversation I'd say that whatever feels alive to me is "today" enough. Although a Chardin speaks to me from the past, it is speaking to me in the present. And if I can use his language to say everything I am compelled by my own experience to say, why wouldn't I? Posted by: rosenak Hi Rosenak and thanks again for your comment. I liked your last comment alot. How we look at art of the past, or maybe the present, is a tricky problem. When I was used the time frame of "Today", I do not think it was arbitrary because now is the only time that I could ever aspire to know a little bit about. I am beginning to think that it is impossible to know very much about any time that in which you are not alive. I understand that art is supposed to transcend time ( or is it timeless?) but I wonder if that is really true. A few months ago, I gave a lecture at the museum on Bierstadt's Mount Hood. While preparing for the talk it became very clear that the while painting is the same, the cultural context and therefore the purpose of the painting, its reason for existing is completely different. When we are looking at the painting we are appreciating it on our terms, not Beirstadt's. It is the same with Chardin. When we look at a painting by Chardin today, it is very difficult not to see it on our terms in the 20th and now 21st century, simply because that is all we know. Our culture and our society has certain values and has trained us to see art in certain ways. It is almost impossible to look at a painting outside of the bounds of what we know. That is not to say that we do not learn or come across new experiences. The further we go back in time, the less we know or understand about the culture or society in which it is made. So the large painting Bloom in theTwombly show was painted in 2007. I was alive in 2007 as I imagine you were so I understand a little about what it was like to be alive during that year. I think what I am saying is that the work always means something different for the people that are around when the work was made. After than it is too easy to superimpose our own ideas and our own culture on to a work. I know that we have been talking about time but I think that almost exactly the same thing could be said about looking at art from different cultures. All of these issues have a surprisingly deep connections to Twombly's own interests and work. Posted by: Arcy I started to extract a piece of your last comment in order set up a reply, but then realized that I wanted to addresss the whole thing briefly. I agree with almost all of it. However, I had meant to suggest that I am not concerned if I don't see Chardin's time or by extension his paintings the same way he did. It is my experience of the paintings that matters to me; Chardin himself doesn't matter, except in an academic sense. Of course it is not that simple -- knowledge of Chardin and his time might might sharpen a painting's voice for me, but I do not defer to what I suppose to be the artist's intentions (which may have been vague or unfulfilled, anyway) when I experience art; it either moves me or not in light of my own experience. Any other way of looking at art is an academic enterprise, and that's fine for what it is, but that's not the essential art experience. So, I wouldn't suggest that anyone to "look at a painting outside of the bounds of what we know." By "arbitrary" I just meant that if I can say that art always speaks in the present and -- as you put it -- "when we are looking at the painting we are appreciating it on our terms", then there is no need to differentiate the past from the present. If you and I are seeing this differently, I think it's just that I don't see this as being a problem. The idea of seeing a painting completely differently from the way the artist intended doesn't bother me at all (as you imply, we can never see it exactly the same way, anyway, even if we want to). When we look at a painting only through what we imagine to be the artist's eyes, we are cheating ourselves out of the best of what it has to offer. Posted by: rosenak Hi Rosenak, I have been thinking alot about your comment for the last few days, even when I have been trying not to. It raises some fundamental issues about the create and experience of art that are difficult to resolve. I also think that this discussion relates directly to Twombly's work because he spends alot of time thinking about sources from the past. Although this discussion is about visual artists, I imagine that it could also easily apply to writers, poets and playwrights as well. I am not sure that an artist ever chooses the work that they make. They make the work that they are compelled to make. On one hand it is easy to see that to make any kind of work requires substantial investments of time, training and often economic sacrifice so it should be spent on something that they believe in. I think that the issue is still deeper. It is simply who they are. An artist does not exist in a bubble. Externally, they are part of a society and a culture that exists within certain geographic, political and economic environments. As important as those environments are to informing the work, I think that direction of the work has to come from the artist themselves, and sometimes with their peers, in the form of an internal dialogue that gives structure and form that would give the work a trajectory. Let's go back to Chardin although this could easily apply to Twombly as well. Why does he paint the way that he does? If he painted more like Fragonard, his work would have been sweeter and easier to understand, he would have made more money and been more successful. That is not a choice that he had. He made the paintings he had to. Who wants to live with rotting meat? Most people have a love it or hate it approach to Twombly's technique. Twombly's a great painter, couldn't he paint a different way to make his paintings more accessible? Again, no. He is who he is and these are the paintings that he makes. Every artist has issues or questions that drive not only the current work but also the next one and the one after that and so on. I think that it is precisely these intentions and motivations that provide the artists context for the work. It also these intentions or this internal dialogue that is almost immediately lost in time. When we are looking at only the formal propeties of a painting, without the intention of the artist, we see only what we want to see and not the world that the artist was trying to create for us. We end up missing a critical context of the work. The lack of context sets up an experience so that the work is to easy to see as isolated formal objects and not part of a larger dialogue. I understand the problem. The work survives but not the artist. Although this context is missing, I think that it is worthwhile to understand fundamental contradiction that it articulates, that the issues that drove the creation of the work are precisely those that are least accessible. When end up looking at the work out of context we end up seeing what we want to see or we see what is universal. In both cases it probably ignores the intention of the artist that made the work in the first place. It is too easy to make the work what we want it to be and not what the artist was trying to articulate in the first place. Posted by: Arcy Knowing something about the artist, his/her intentions, his/her time and place, can deepen the experience of the work, it's true. On the other hand, by the same token these things can narrow the experience as we strain to fit the work into prescribed parameters. (It's good to remember, too, that artists can be unreliable guides to their own intentions, sometimes by design but more often because -- unless your work is the kind of "illustration of an idea" we were talking about -- well, it is just fucking impossible!) Beyond that point, I think I'm getting lost. I'm not sure why you say that without the context you describe a piece is reduced to its formal elements when you have just said: "When we look at a painting by Chardin today, it is very difficult not to see it on our terms in the 20th and now 21st century, simply because that is all we know. Our culture and our society has certain values and has trained us to see art in certain ways. It is almost impossible to look at a painting outside of the bounds of what we know. That is not to say that we do not learn or come across new experiences." In any event, I just do not respect the artist's intentions as unimpeachably authoritative in the matter of how the work should be viewed. Instructive? Hopefully. But that's all. I think that measuring a piece against what we suppose to be the artist's intentions is a vain exercise that while possibly interesting or even enlightening turns art into artifact. Posted by: rosenak Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)