|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Cochrane & Middendorf + Gray & Paulsen at The Art Gym  Attic clutter that eventually became exhibited as "The Dregs" Like no other people except the ancient Egyptians, Americans are obsessed with the accumulation of stuff. The mantra of ownership of property (via enlightenment philosopher John Locke) practically defines our consumerist national character. Philosophically, Locke considered property both material and more abstract to be a natural right, a kind of talisman imbued with the value of labors undertaken and exchanged to acquire them. America was the first country to apply these rules evenly across all social strata.  King Tut's stuff Still, the Egyptians differed from Americans in one telling respect; property and death were entwined in a hermetic dance of preparations, while Americans do everything in their power to avoid addressing death… often using stuff as a distraction from the inevitable. Alas, no pack rat has enough stuff to keep death from getting in the door. Still many try. Exploring similar memes two well curated shows at the Art Gym; Brandy Cochrane and Paul Middendorf's, "The Dregs" and Anna Gray and Ryan Wilson Paulsen's, "The Imaginative Qualities of Actual Things," do an interesting job of prompting philosophical discussions around the stuff that people own.  Important documents and Photos from The Dregs The Dregs by Cochrane and Middendorf is a kind of fantasia collaged from the remnants of an estate sale that Cochrane oversaw. These "dregs" thus were unwanted detritus that couldn't be disposed of commercially. Interesting how instead of the landfill, all of this stuff heads off to a university art gallery. The strongest aspect of this exhibition is the fascinating way in which art picks up after commerce loses interest and through artistic intervention somehow reanimates the property's ghostly owners in a cheerful, mostly non-creepy way. Beginning with a slide show at the start of the exhibition, we are shown some of the original context from which the exhibition has been curatorially organized into; several walls of correspondences, some party balls, a collection of antiques and two rooms… each devoted to Larry and Elsie as a kind of nostalgic paean to their departed owners. There is also small wall of personal and official documents and photos such as Ross' Oregon drivers license, Ross's son Larry's report card and an appraisal of Ross's wife Elsie's jewelry successfully brings a piece of the three former owners to life.  correspondences and other papers The largest wall of correspondences and other papers acts as a kind of avalanche of sentiment and detail, with tantalizing tidbits about the senders and their recipients. Some of the letters contain a lot of personal detail but it's the sheer # greeting cards which indicate a lifetime of birthdays and illnesses. I'm a historian so I'm used to filtering through correspondences but to many this sort of glimpse into other people's sentimental life is probably disarming. As a historian I found myself wishing for a step ladder since many elements were simply out of reach. It turns an archive into a daunting object like the ghost of a hallmark store filled with used cards returned to the shelves… it's paradoxically a pop and personal display, both accessible and inaccessible.

More visual were the various party globes fashioned by Cochrane and Middendorf out of poker chips, satin ribbons or my favorite, the death star disco ball. Somehow craftily reanimating the deceased's more pied belongings and turning them into a solar system of fun in one corner of the gallery was a very effective tribute. It's kind of the inverse of the velvet underground's "All of tomorrows parties," instead these are all of "yesterday's parties"… and thus more of a way to reanimate the ephemeral fun these objects were once a part of. The globes are of Elsie, Larry and their son Ross's life but re-charged through the intervention of Cochrane and Middendorf… it is a kind of cross-generational meeting of the party people.  Beloved Mother More personal and somber is Elsie's room which contains a bed, matching lamps and a rack of empty clothes hangers (among other things). The most telling object though is "Beloved Mother" a high backed easy chair that Cochrane has sewn in an elaborate pattern of various fabrics... even undergarments left over from the sale. In effect the artist's intervention occupies the now empty seat with the textures of a former life. To me the Octopus tentacle-like patterns also look like stylized art deco hair and it's probably the most artfully effective piece in the show because it is so nostalgic yet somewhat of an anthropological and artistic tribute.

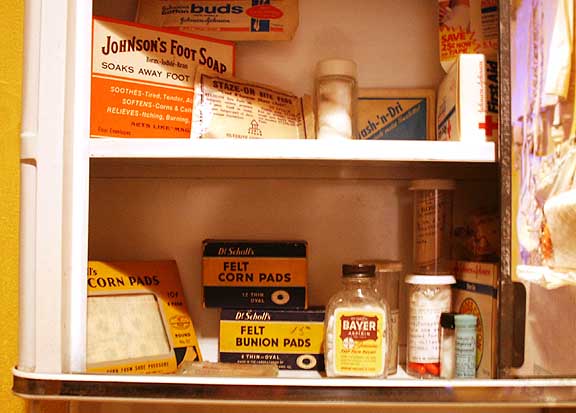

In contrast to Elsie's, Larry's room feels more abstracted as the space is dominated by the black skeleton of a mattress with the word crestfallen written in lavender neon letters. What's more the shadows thrown by the piece project a form that eerily looks like a house. It feels like an unfinished poem and might be the most somber aspect of The Dregs, while at the same time definitely trying hard to be art. I wonder, does it break the spell of the show or add to its mystique? To these eyes it wouldn't hold up as an individual piece but it's the fitting touch of tragedy and darkness that completes the show. This is especially true since an array of soaps and cleaning utensils called Clean/Dirty is nearby.  Clean/Dirty Clean/Dirty is a wonderfully guileless but paradoxically filthy array of cleaning ephemera (both soiled and pristine) laid out like a mini museum. It's my favorite part of the show. Somehow this archeological display offers up ancient soaps like "Cashmere Bouquet", "Dial" and "Refresh" like Etruscan artifacts. In a way it's a Duchampian ready made or quirky Warholian collection like the cookie jars except this collection seemed more ad hoc. It's simply a case of stuff accumulating during travel and a curator laying it out in a coherent fashion.  The tiny back room is a more claustrophobic exploration of stuff with its multiple Larry Hagman puzzles; several Dr. Scholls felt corn pads and boxes of Sprecker's Powdered Sugar. It brings the exhibition back to the inexplicably strange things people keep well beyond any logical use. The packaging serves as a time capsule for each objects respective era. Despite all the stuff and tantalizing details it's a somewhat meager portrait of its former owners but succeeds as an incidental time capsule of Americana. Had the exhibition included a car it would have said much more, but being valuable an automobile wasn't going to be a remainder of an estate sale. Still it is all of this ephemera that makes The Dregs so different than the way Ed Kienholtz was buried in his Cadillac. Here at the Art Gym, the former owners of all this stuff are portrayed more for their incidental humanity rather than a gesture at immortality. The difference is the way artists become egoists of stuff, seeking to transform material and undo or render ambiguous the Lockean causality of value for stuff… whereas a typical American person simply wants to possess it. What does it say about western civilization that much of the art since Rauschenberg has so popularly sought to create combines like the globes and chairs in this exhibit? Why is experiencing all this stuff both dread inducing and fascinating? Possibly it is because all American families leave a similar wake of consumer activity and we can read it like a more detailed obituary.  a pile of burnt newsprint from "The Imaginative Qualities of Actual Things" Whereas the, "The Imaginative Qualities of Actual Things," is one of those rare situations where a book becomes an art show. Specifically here, artists Anna Gray and Ryan Wilson Paulsen lost most of their belongings when the house they were renting caught fire. They made a book around the experience called Integrating a Burning House and The Imaginative Qualities of Actual Things is the follow through exhibition. The show consists of a burnt Apple G5 computer. A stack of burnt newsprint, a charred guitar neck, a burnt Joe Macca post card and an OSB shipping crate full of cardboard boxes and a video that display the text from the book. The most important lines being, "What is lost never fully extinguishes." Thus, all of the burnt items are essentially ruins of their former selves and as such possess a sort of romantic quality… not unlike the artifacts brought back from the Titanic or wreckage from the World Trade Centers. For example, the burnt newsprint is neatly tucked in beneath an avalanche of paint pried from the gallery walls that seem to flow over them… a nod perhaps to the act of displaying a ruin in a gallery setting which further fetishes their former-ness. In reality was the stack of newsprint ever as cool as it is now? This is where Gray and Paulsen are dealing in imaginary qualities… and it's up to the viewer's subjective experience. Out of necessity the artists have moved on by transforming misfortune into art. Here it seems like a clear victory of life becoming art. Whereas, the burnt mail art from Joe Macca is definitely less than its former self. As a ruin it feels incomplete and not at all like one of Macca's hilarious bravura moments. It is more of a casualty now. The operative issue here is that the newsprint built up mystique by first becoming a ruin and then through intervention, art…whereas the ruined Macca can no longer operate in the way the artist intended as too many details have been obscured.  Crate made of OSB, video and Guild guitar neck Another effective ruin is the charred neck of Ryan's 1967 Guild guitar. Most guitarists are attached to their instruments a lot more than a G5 computer. For example, a computer like the one on display here can be replaced but a guitar is a sensual thing. Most experienced guitarists can recognize their instrument blindfolded, even compared to the exact same models. Thus, in both the guitar and computer's case there is a real sense of loss but it is different. The guitar had the potential to be a kind of life partner, whereas the computer is a tool and an archive... though many more people can probably identify with the G5 computer.

At this point it is obvious that the viewer's interpretation of these objects will be very different than Anna and Ryan's and this too creates a sense of empathy. Perhaps to enhance the empathetic impulse the OSB crate in the center of the room plays some video text that divulges a little of the compartmentalized feelings the artists have about their things. There is a sense of a grieving process that has mostly passed and the text seems to be mostly a resignation to the fact that they have moved on while others haven't yet sated their curiosity. Overall, it's a successful show and the stack of newsprint is an excellent art object in itself. Still, I feel like the book really ate this exhibition's lunch. Maybe it's because The Dregs exhibition in the larger space was so expansive and this one felt like such a footnote. Still, it's that feeling that Gray and Paulsen have moved on already that is the show's lasting legacy... so (quite poetically) to be a footnote isn't such a bad thing, in fact it is natural. I can't wait to see what these two do next (actually the two have married and a baby is due any time now). Overall, these were two successful shows that mine the well worn "sincerity art" one finds in a lot of university art galleries these days… but in both of these cases it's the individual quirks and not relying on "community building" activity that makes them better than most. Instead, what is on display are somewhat personal treasure troves… one for three lives now gone and in the case of Paulsen and Gray; a need to move onto the next thing, with the promise of new stuff to fill a life with. Americans still have too much stuff but these shows suggest that belongings aren't the real problem, simply the quantity and the level of meaning that is attached to consumption with too little discrimination. Posted by Jeff Jahn on January 19, 2010 at 2:56 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |