|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

The Figure Idealized at PAM and Reed College  detail of a Antione Catala video at the Cooley Gallery When I entered the Cooley Gallery at Reed College on a dark Tuesday evening I was accosted by a hauntingly intrusive TV set. Antoine Catala's "Portrait of a Curator" captured me convincingly unto undulating surfaces and psychedelic glitches. Thereafter, a distortion of melted profiles sank in and out of focus conjuring images of expressionist portraits. Dissected like a set of Muybridge's motion photographs, the faces contained by Catala's screen brought questions of psychological content, of the ghost within the machine, and the very nature of recognizing the figure. Thus, It was under the influence of Catala's warped imagery that I was introduced to the myriad of old master drawings constituting "The Language of the Nude: Four Centuries of Old Master Drawing".  The language of the Nude (installation view) Reed College (ends December 5th 2009) The show is divided by region, focusing on work from Italy, the Low Countries (mainly the Netherlands), France and Germany, spanning a time period from the early 1500's to the late 1700's. Each wall of the gallery depicts a chronology of the nude as it was studied in a given region. Overall, this collection focuses on the development of the academy surrounding the nude as well as the methods of study. Beginning with Italy, the engine that would eventually power study of the nude across all of Europe, we see the development of private and public academies of art. Before the rise of these centers artists relied heavily on the works of ancient sculpture and those of established masters such as Raphael, Caravaggio and of course Michelangelo. On an interesting side note, teachers warned that the "vigor" of Michelangelo's work could easily overpower young artists and cripple the development of their own aesthetic.

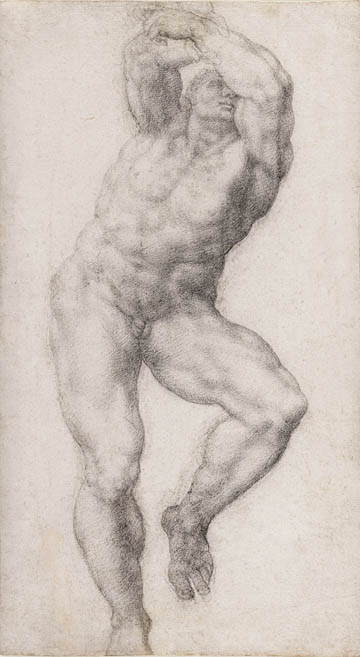

Danele da Volterra after a figure from Michaelangelo's Last Judgement One of the best aspects of the collection is the intimate and novel understanding of nude academic study it provides. It is easy to forget how fundamental differences in culture and technology created quite a different approach to drawing the figure. Not only were the ideals different but the methodology as well. In example the amount of time given with the live model was limited by the rank of the artist, as well as by the season of the year. Furthermore, Artists used cadavers regularly, even to the extent that painters came to understand anatomy as well as surgeons. The collection also highlights the cohesiveness and connectivity of thought between artists of the time in their struggles towards the ideal nude. It was thought that no single figure could be used to produce this idyllic form. Rather, artists drew upon a mental bank of figures from master frescos and paintings blending them with their own intuitions. The imperfections of the individual model were to be overlooked and redrawn a step closer to standards of gods. A painting was regarded in a similar manner to prose, as a language in which the expression of mythical and allegorical stories could be properly told. Viewers took great delight in discovering the hidden meanings behind symbols and deciphering coded references the artists included. Drawings like the ones of this exhibit could be thought of as rough drafts, ultimately to be used as careful preparations for paintings.  Albrecht Dürer, Nude Woman with a Staff, 1498 (Pen and brown ink on cream laid paper 12 1/8 in. x 8 5/8 in.) Crocker Art Museum, E. B. Crocker Collection I was happily surprised to see quite a vast variety of approaches to figural representation within the show. Even the strict regulations of the academy could not suppress the will of individuality and the desire of expression by each artist. The delicate but loosely rendered ink washes that compose Jacob Jordaens' "Satyr and Peasants", mimic a caravaggesque glow, figures barely identifiable by brown blots and the slightest touches of a brush. Meanwhile Durer's "Female Nude with a Staff" is carved by his typical hatchwork, black lines slicing across every fold on her skin.  Raphael's Woman with the Veil (1514-1515) at the Portland Art Museum In addition to the master drawings at Reed's Cooley Gallery Portland is lucky to have another compelling and rare old master work, Raphael's "Woman with the Veil" at PAM. Raphael's portrait and "The Language of the Nude" feed each other, allowing one, if just for a moment, to shed the centuries that have passed enjoying the figure with innocent delight. "Woman with the Veil" (La Velata as it's known in Italy), is placed in a sanctuary seemingly hidden from the gaze of Portland Art Museum's inferior Renaissance works. Walls of velvety dark purple were an ideal choice to encourage the golden yellow glow that so beautifully emanates from La Velata's bosom. A solitary wood bench waits patiently in her haven, enjoying stillness and hushed mumbles of passersby. At the advent of viewing Raphael's masterpiece I took it upon myself to step into the shoes of a student in the academy, making my voyage to a work only dreamed about. I took out my sketchbook and graphite and began diligently tracing the soft curves of La Velata's profile. As we engaged each other torrents of emotions overcame me. Her gaze brought about a deep carnal longing echoed by the hand draped firmly upon her breast. The subtle duality of her smile, forlorn and lustful, called me like a siren, dragging me ever further into her limbo.  La Velata (detail) After only an hour or so with La Velata it became obvious why so many students trudged across Europe to feast upon Raphael's figures. The ease with which he engages human form is stunning. Nimble brushwork within the folds of La Velata's dress provide endless enjoyment and the dutiful proportioning of her profile is exceedingly impressive. Having spent hours with preliminaries, sketches, and preparations, made La Velata's finalized form all the more fulfilling, like the satisfying click of the last piece in a jigsaw puzzle. I want to step back again to the show at Reed College as there is a key section I left out. It is important to preface this portion however with the thoughts and currents running through the Langauge of the Nude and La Velata. In both shows we find artists striving for idyllic beauty. But more than just attaining perfection of human form these works show a movement towards the embrace of real human qualities. Ironically, this includes the imperfections humankind such as the single strand of hair scribbled upon La Velata's forehead. Though old masters may not have realized where the figure and art were headed, they foretold its destiny in their desire to beak from ancient notions of beauty.  Installation view of Antoine Catala's "Video Portraits for Vertical Televisions" at Reed's Cooley Gallery Which brings me to the final part of the show at Reed's Cooley Gallery, in a room not unlike La Velata's sanctuary where the rest of Antoine Catala's work, "Video Portraits for Vertical Televisions" reside. There is a distinct hum as one enters this area creating the sensation of a current running through and between the viewer and the portraits. Each set, comprised of one TV atop another, stands almost derelict showing slight movements in the decaying cathodes. With distinct personalities the portraits hark to Nam June Paik's "Family of Robot", devoid though, of his quirky attitude. The forms of beauty in Catala's work are gnarled and broken. He removes the mask of the figure revealing the boney structure beneath, challenging both our identification of form and notion of the screen it rests upon. This stripped down version of the figure stands in great contrast to the works in the room adjacent, yet they head similarly towards representation of the figure in gesture. Both try to catch a glimpse of something fleeting, of a moment captured with the figure balanced in motion. There is a sense of connectivity evoked by Catala's work. In part this is the nature of the medium he uses but also the portraits themselves come to life like the wired circuits of a processor or the flowing sap in a tree. In the context of our globalized world I began to see Catala's figures as familiar faces from television. Images of newscasters, show hosts, and Hollywood stars took the place of these unknown profiles beckoning me far beyond the solitude of that little room in back of Reed's Cooley Gallery. After a bit of reflection the figural works I have seen have come speak about more than just the nature of idealization and beauty. They call upon the will of humans to discover and reveal, that which connects us. From La Velata's gaze, so full of desire we can't help but feel her lust, to Catala's clever deciphering of flesh on screen, we understand the image of the figure as a common bond. When we see the figure we see ourselves, our brothers and sisters, and our martyrs and saints all at once. As redundant as it sounds the figure gives us our humanity and we make the figure akin in return. Posted by Jascha Owens on December 02, 2009 at 11:56 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |