|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

It's Immaterial In the current pair of exhibitions at the Museum of Contemporary Craft, curator Namita Gupta Wiggers dives headfirst into one of the big questions that plague "marginalized" artistic disciplines. The shows resurrect that classic query: If it's not "fine art," then what is craft?

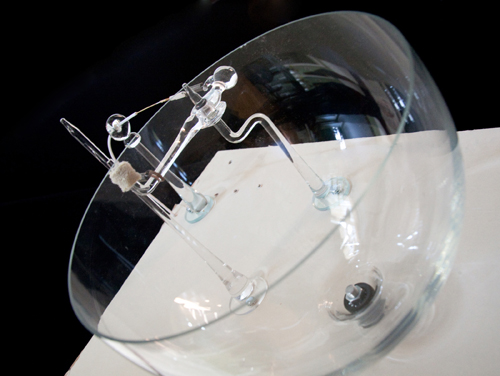

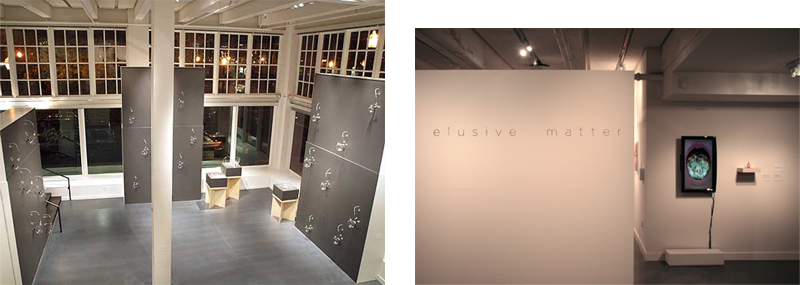

Ethan Rose & Andy Paiko, "Transference," 2009, installation view Wiggers tackles this issue by attempting to tease out the relationship between craft and material. If craft is typically understood as "a category of objects created through the transformation of raw materials by hand," then how far can the boundaries of a work's materiality be pushed while still retaining the label of craft? The works in Transference and Elusive Matter approach the question of craft's materiality (or lack thereof) through sound, video, photography - almost anything but traditional craft objects.  Bowl from "Transference," image courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Craft. In the museum's downstairs gallery, glass artist Andy Paiko and sound artist Ethan Rose perform a collaborative physics experiment in the installation Transference. The project was inspired by the glass armonica, an instrument that was popular in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Although the armonica has since fallen out of favor, most people recognize the basic technique - fill glasses with water and employ friction to create a sound like a "singing" wine glass. Paiko and Rose have reinterpreted the instrument, constructing a series of spinning glass bowls connected to glass needles with fabric tips that stroke the edges of the bowls to produce an ethereally beautiful tone. The bowls were built by blowing glass spheres, which were then cut in half and ground down until they were tuned to the closest note. Because the tone couldn't be determined before the glass was cut, the artists felt that the material itself took on the role of musical composer.

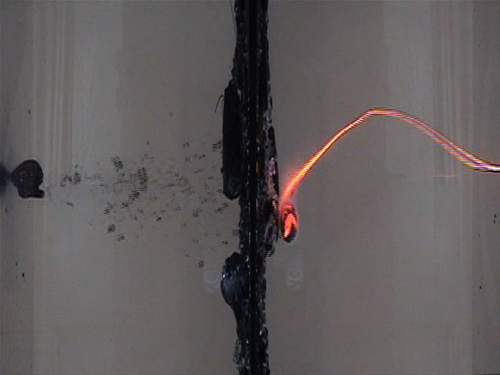

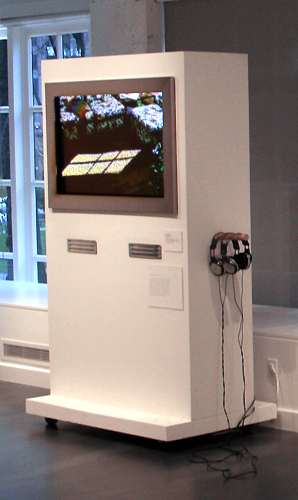

Approaching the project as a site-specific installation, Paiko and Rose placed 37 glass "armonicas" throughout the downstairs gallery at the Museum. Although the bowls themselves are visually quite beautiful - each is a subtly different size and shape with unique detail work in the glass needles - it's the aural experience that really makes the exhibition. The glass naturally tunes in the 1000-4000 Hz frequency range, which makes it difficult for the human ear to determine where a sound is coming from. Also, the mixing board controlling the bowls is programmed only for duration, randomizing each individual element's contribution to the composition. The result is that the viewer/listener is surrounded by a haunting, slowly shifting chorus that seems to come from everywhere and nowhere at once. It is the ephemeral experience of Transference that departs from the expected materiality of craft. Although Paiko and Rose engaged in meticulous planning and labor in the physical construction of the glass bowls, the final work of art is most easily accessed when the viewer/listener closes his or her eyes and loses track of that physicality, becoming immersed in the sound of the piece. Thus, though the project is installed in a museum of craft, it feels more at home in the traditions of soundscape and sound sculpture. As a collaboration between established glass and sound artists, it's no surprise that the project is inherently interdisciplinary, but by exhibiting Transference in the Museum of Contemporary Craft, the artists and curator ask us to consider it specifically in the tradition of craft. Or, perhaps it would be more accurate to suggest that the project asks us to reconsider the discipline of craft itself. If we expect to locate craft in the material objects that it produces, how do we consider a craft endeavor that is most effective when the material itself disappears into the experience? The primacy of the intangible atmosphere becomes an assertion of craft into the sphere of "fine arts," which have long been preoccupied with exploring the disconnect between objecthood and experience (see Conceptual art, performance, happenings, and, most relevantly, sound sculpture). When something that is undeniably crafted insists on being experienced abstractly, it demands an evolution of our understanding of the term "craft." Yet it would be incorrect to say that the success of Transference is totally divorced from its material. As you sit in the gallery and listen, a series of soft clicking and whirring sounds can just barely be heard above the bowls' song. These sounds come from the mechanisms that are moving the bowls, and while the artists strove to muffle them as much as possible, their gentle persistence ultimately brings the listener back to the visual elements of the piece. The sounds encourage you to open your eyes and seek out their source, which inevitably brings one to a close inspection of the bowls themselves. And this inspection is very aesthetically rewarding - the bowls are beautifully crafted (as it were), the needles are all elegantly made, and watching the bowls spin is almost as hypnotic as listening to them. By themselves, the visual elements of Transference in no way challenge accepted notions of craft - these are objects "created through the transformation of raw materials by hand." But as the installation gives way to an immersive auditory experience, Transference decisively rejects materiality as a liminal definition of craft.  "Elusive Matter" installed at the Museum of Contemporary Craft 2009 Elusive Matter, a three-person exhibition in the upstairs gallery, deals more explicitly with the issue of material and craft. As Wiggers notes in her introduction to the show, photography and film typically play a documentary role in the world of craft, showing us the process of making but not functioning as "craft objects" in and of themselves. Elusive Matter is made up almost entirely of videos and photographs that "engage the temporal and spatial elements of film and photography to reveal how matter performs." In other words, rather than exploiting material to investigate objects, the artists in Elusive Matter exploit the properties of photography and film to investigate material itself.  Lauren Kalman, installation view of "Hard Wear (Tongue Gilding)," 2006 (shown in 2009) As you walk up the museum stairs, the first piece you're confronted with is Lauren Kalman's Hard Wear (Tongue Gilding). The primary element of her installation is the video, which is a 12 minute looping close-up of the artist's tongue, protruding from her mouth and gilded with gold leaf. Her enormous golden tongue fills the screen, twitching, trembling, and dripping with saliva. On a platform beside the video screen sits a small glass jar, streaked with gold and partially filled with liquid, the materials labeled "saliva and gold leaf." The presence of the jar inverts the relationship described above between documentary film and craft object. In this piece, the object itself fills the documentary role, albeit one that is more probative than explicative. The small glass jar offers physical proof of the art work that is happening over and over on the screen, a small nod to the inherently suspect nature of film.  Lauren Kalman, still from "Hard Wear (Tongue Gilding)," 2006, image courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Craft Watching the video, the myth of King Midas immediately comes to mind. Midas was the monarch who nearly starved to death because his touch turned everything to gold, the result of an impulsive wish granted by Dionysus, a god who represents pleasure, intoxication, and excess. As time passes in the video, the artist's tongue begins to twitch more violently and saliva drips more and more rapidly, visual evidence of her increasing discomfort. The viewer wonders if this isn't a sort of playful punishment for the material and cultural excesses often represented by gold, the artist both mocking and suffering for this materiality with her protruding tongue. At the end, Kalman slides her gilded tongue back into her mouth, a satisfied half-smile gracing her closed lips.  Lauren Kalman, "Lip Adornment," 2006, image courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Craft Kalman's work explores Wiggers' received definition of craft (above) in the relationship of raw materials to the body. Unlike jewelry, which uses the "transformation of raw materials by hand" to create an object that will eventually - often only hypothetically - relate to the body, Kalman skips the middle step and applies raw material directly to herself. In Lip Adornment, Kalman's second piece in the exhibition, the artist once again presents her mouth, this time with her lips mostly closed and encrusted with gold leaf and jewels. The close-up photograph is perhaps even more visceral and discomfiting than the Hard Wear video - the camera has caught details as intimate as the pores in her skin and the enamel on her teeth, and the gold and gems look more like growths or sores than jewelry. Much like in Transference, Kalman's original process - bodily working with raw materials - seems to be an act of craft, but the viewer's final experience bends the tradition of the craft object. Like most of the other works in Elusive Matter, Kalman's pieces engage the viewer as photographs and videos, not objects or records of objects, making the persistence of objecthood irrelevant in the pursuit of craft.  Mark Hursty, still from "El Mort de la Massa," 2008, image courtesy of the artist Also included in Elusive Matter is Mark Hursty's El Mort de la Massa, which stays engaged with material but seems even further abstracted from the crafting process. The video records and transforms the effect produced when hot glass hits water, creating a visual loop that is reminiscent of a delicate sort of action painting. Although the work relies entirely on the physical properties of matter, Hursty has abstracted and mirrored the process being filmed, thus moving beyond a simple interrogation of the materiality of glass. Instead, the video uses glass to engage questions of movement, temporality, and beauty, allowing material concerns to be playfully and elegantly subjugated to visual experience. El Mort de la Massa won second place in the 38th Annual Glass Art Society International Student Exhibition, which was hosted in June 2008 by the Museum of Contemporary Craft. Hursty expressed surprise that the video was even allowed into the show - one of the requirements for submission was that the work be physically made of glass. The fact that the piece not only made it into the student exhibition but also won an award suggests that the world of glass - one element of the greater umbrella category of "craft" - is engaging in the kind of self-reflexive exploration that once transformed the Western art world's understanding of painting. Although the piece does not appear to share many qualities with the minimalist work of artists like Melissa Dyne, Hursty has engaged in a similar project to break down the elements that define a work of glass.  Mark Hursty, "Installation view, Shelter," 2008, image courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Craft Hursty's second piece in the exhibition, an installation view photograph of his 2008 project Shelter, is probably the most documentary work in the show. Aesthetically, the photograph stands up well on its own, with lushly saturated colors and an elegant composition that captures the timeless quiet of a snowy, empty street. But what is most intriguing about it is the mysterious glowing orange shape protruding from the building, which turns out to be the Shelter installation. When he was still a student, Hursty built Shelter as a way to explore the "in-betweening" (artist's own phrase) of the process of blowing glass. He constructed a large rip-stop nylon "tent" around the entrance to the glass studio, capturing the waste heat from the glass blowing process that is normally just shunted out of the building. The hot air inflated the fabric and created a warm antechamber between the door to the building and the chilly winter air. (The tented space was apparently not so comfortable - or popular - in the warmer months.) By luck, the outdoor lights trapped inside the tent caused a glowing hot spot in the photograph that resembles the hot spots seen in the glass in El Mort de la Massa as it first hits the water. With the Shelter installation, Hursty played with one of the mostly forgotten by-products of the glass blowing process, addressing that "in-between" space in the process from material via artist to finished product. The project doesn't challenge definitions of craft - the fabric tent seems perfectly at home in the mode of craft installation - but it does take an interesting perspective on the "important" materials and steps in the process of crafting.  Installation view of Jane Aaron's "Traveling Light," 1985 (shown in 2009) The final piece in Elusive Matter is Jane Aaron's Traveling Light. Aaron, who has worked in the field of animation for over 30 years, is probably the most established artist in the show, but her work seems the least invested in craft. Wiggers admitted that Traveling Light was the last piece added to a show that was already constructed, and while the video doesn't quite feel like an afterthought, it seems to engage less with the issues at the heart of the exhibition. Traveling Light still experiments with materiality, but in a fashion that invites the viewer to contemplate the illusory nature of film and animation rather than the material nature of craft. The two-minute piece follows what appears to be a square of bright sunlight coming in through a window as it travels across the interior of a house. The light graces bedroom walls and worktables, sliding through almost the entire house until it lands on the floor. A woman in a housedress and heels walks in to sweep up the square and the trick is revealed - the square is in fact carefully constructed from yellow paper, not sunlight. The climax is a fairly entertaining "gotcha!" moment, and evidence of excellent stop motion animation, but it does little to engage the viewer in ruminations on the nature of matter. A physics fan, however, might enjoy the play on the dual nature of light, which is thought to be both a wave and a particle. Although Traveling Light is a last minute and slightly ill-fitting addition to Elusive Matter, Wiggers' inclusion of the film does ask us to expand our understanding of craft in a different way. If we can accept that the result of a craft project may not be a craft object, then the practice of animation, particularly stop-motion and other human-hand methods of animation, probably fits more easily into definitions of craft than it does "fine art." It is the transformation of raw materials - paper, ink, clay - by hand into a film object. Thus animation can act as a bridge to understanding a non-documentary relationship between craft and film.

The truth that I see emerging from all these games with liminal boundaries, materiality, and "craftiness" is that the definition of "craft" simply doesn't matter. An artist can look to categories like craft, fine art, functional, abstract, etc. when seeking out historical and traditional roots, but in practice the boundaries are only interesting when they blur. Can something be a "work of craft" if it isn't a material object? The question seems immaterial. Posted by Megan Driscoll on December 31, 2009 at 8:47 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |