In a world increasingly fixated upon the propulgation, proliferation, production, fetishizing, and pushing of objects and things that we somehow need, it is ironic that we question less and less the inherent significance of these particular objects as symbols. They literally fill up and inhabit the space of our lives in the most tangible way, reflecting status, wealth, and even personal ethical codes. Yet we look upon these objects less and less as societal talismans, intrinsically weighted and dripping in all of their reflective glory, less and less as what they should be: cheeky mirrors asking us to understand our behavior and, even more, our desires.

Art History's dissection of meaning through form is a given. The beauty of history's most noted works pique our mental curiosity through the greatness of their form. The gateway of beauty to spiritual validity is only human; we want beauty to have meaning because we can feel it.

Sistine Chapel Ceiling, Michelangelo, 1508-1512

We stand in awe before this beauty, terrified and humbled in the presence of an incomprehensible greatness before which we are mystified. Art historians and critics devour the formal qualities of art like cryptographers, anatomizing the mechanics of art works as they reify meaning both implied and accidental.

'The Sacrifice of Isaac', Carravaggio, 1603

The objects of decor, of hobby, and of utility are often objects relegated to the categorical moniker of 'craft'. The general assumption habitually conduced in regards to the realm of craft is that it falls into one of these categories. 'Hand-crafted' and the elements of 'craft' are terms dedicated to the aspects of making and materiality while coincidentally denying an object's further symbolic investigation. Yet the tide has turned, in both ideology and practice. In a pluralistic contemporary art world, all materials are fair game for the creation of language and thus the expression and/or discovery of a zeitgeist. Unfortunately the general, collective consciousness is well known to be the slowest and most stubborn to move and shift; this is where the efforts of 'Call and Response' at the Museum of Contemporary Craft come into play.

The current exhibition at the MOCC, Call and Response, introduces an investigation of the world of objects and decorative form through an innovative method involving what antiquated thinking might see as juxtaposition, yet what visionaries see as compliment. Namita Wiggers, curator at MOCC, creates immediate conversation between craft and material oriented art works and esteemed contemporary minds by placing recorded interviews and essays next to each work in the exhibition. The technique is provocative in the effect each genre has on the other. Wiggers has selected works for the exhibition which walk a delicate line of singing praise to material based media while standing alone as works of art in their own right. This conversation richly extends from work that challenges the notion of contemporary utopia in your kitchen sink to mental musings echoed in embroidery. As each conversation plays out, the relevance of each party resounds exponentially. Wiggers not only brings to light a new way of seeing material, but also fervently directs our attention towards the need for and importance of contemporary criticism, a call in which a societal response is needed.

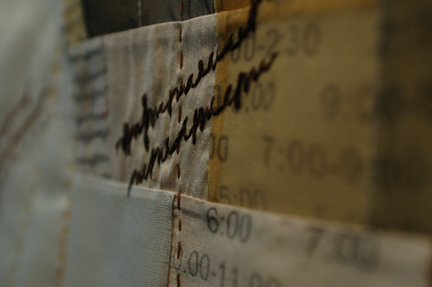

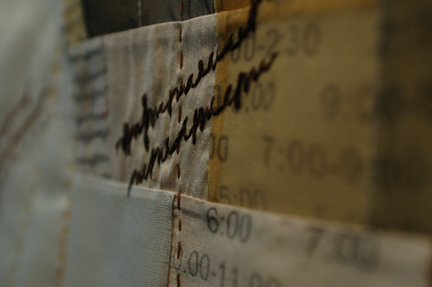

"Feasible" (Detail), Jiseon Lee Isbara, 2008-2009

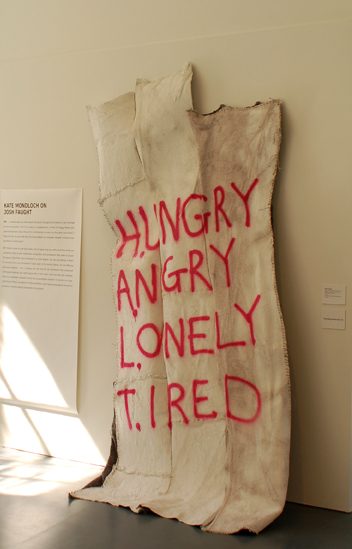

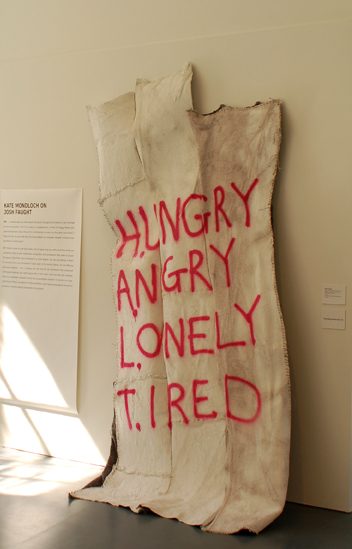

Bringing the heady nature of this conversation to craft reverberates upon leaving the gallery and is, in essence, a request to critically look and think about the visual world around us. By encompassing such a breadth of work into one exhibition, Wiggers extends the way of looking and thinking across habitually separate genres. Studio Gorm's questions of sustainable design on a day to day basis share a gallery floor with Josh Faught's H.A.L.T. piece, a fleshy fabric martyr asking to be saved from itself.

"Four Signs to Suicide Prevention", Josh Faught, 2009

Wiggers reminds us that the analytical tools with which she presents the viewer are able to be utilized across a vast range of situations and media.

Makers understand the inner workings of an object. In the U.S., the famed 'Made in the USA' insignia as a stamp of national pride circulates at an ever diminishing rate. Perhaps it is this occurrence which separates us increasingly from the made world around us. Things made by hand are wondrous oddities, valued extensively and almost fanatically, and by which we are enthralled for their almost exotic quality. Matt Johnston's essay on Karl Burkheimer pointedly expounds upon the prevalence of this state:

"A tool-making species, in this apocalypse of our own creation, we are losing touch with basic hand-eye skills required to fashion, manipulate, and interpret objects; in effect losing the ability to re-imagine and re-make the world, and are instead becoming mere passive consumers of machine-fabricated commodities."

Culling the essence of material based language and catalysing conversation around it in the midst of this challenging current of fabricated commodity and endangered published criticism is not an easy task. This exhibition needs to act as an introduction (some may even say a reintroduction) to looking at expression in craft and material as the reverberation of an artist's voice. Each call and response respectively stand alone yet require the other to be thoughtfully considered and digested, as they become increasingly diminishing critical elements of our society. 'Call and Response' brings these issues to consciousness in a tangible forum as the sudden realization of their habitual absence is felt as a fierce and dumb reality.