|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

East Meets West: An Interview with Sanford Biggers

I grew in the early seventies in Los Angeles. I was influenced largely by the artwork that my parents had in their home which were prints by important American artists like Elizabeth Catlett, Charles White, John Biggers and Ernie Barnes. It was largely figurative and Afro-centric images which were influential for me as well the graffiti that I would see on the streets of Los Angeles and in the train yards. It seems like your art experiences were coming out of your home rather than say being influenced by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) or the Pasadena Art Museum. Is that true? As a kid, I mainly only went to museums on field trips, so my earliest experiences with art were in my parent's and their friends' homes. I did, however, spend time as a teenager at LACMA and California African American Museum where I took art classes on weekends.

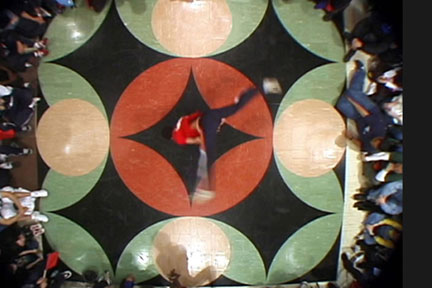

I spent a lot of my teenage years with a graffiti crew going out and bombing (spray-painting), various walls and train yards with graf murals. That was a big part of my early years as a B-boy and I still reflect on some of those forms that I was interested in and I try to bring them back into my work. A few years ago, I did a few different types of sand paintings, one of which was a graffiti version of the Sanskrit word/sound, "OM". It was made of colored sand, poured directly on the floor. A technique that was not too dissimilar from that of Tibetan monks.

Graffiti art is usually transient as well! You can put something up one night and the next day somebody can come by and deface it or put another piece right over it. It sounds contradictory, but somebody could vandalize the graffiti that was already there. So there is the potential for erasure and the general feeling of impermanence in the gesture of making graffiti as well. In the same way, a sand mandalla can take days to create, as my sand paintings did, and be swept up in a matter of minutes, reifies the metaphor of the impermanent nature of life. There is the Buddhist concept that life comes from suffering and suffering comes from attachment. If you do not have that attachment you are liberated.

I did that piece in 2004 and as I had mentioned before, I was a Hip Hop enthusiast since my early teenage years, but there was a point where I felt that Hip Hop became Hip Pop and rarely had that authentic energy that was so important in the first 20 or so years of the art form. It is the criticism that you hear about every musical format that evolves, but in my eyes, Hip Hop as I knew it was dead. So I thought I would make a ceremony to send Hip Hop on its way. This concept is based on an early Shinto and Buddhist ritual of using the singing bowl in a house hold altar or using the singing bowl as an obeisance, a ritualized form of respect, for deceased ancestors. I purchased gold and silver Hip Hop jewelry in Harlem and Shibuya and working with several artisans around Tokyo, was able to m create a series of singing bowls from the melted down jewelry. I then took these singing bowls to a Soto Zen Temple and performed a bell ceremony with the head monk, of the temple and fifteen other participants.

One of the hallmarks of traditionally African and black forms of music is improvisation. It is common to see these forms in Jazz but you also see this Hip Hop in the form of Freestyle. I wanted to set up a way for all of the participants to perform without having to train or read notation. I created a drawing not too dissimilar to the mandalas that I had been using for some of my earlier works, where each participant was denoted by a circle. The participants were instructed to follow the arrows in the drawing and ultimately play in round Within the diagram were instructions for each person to know in what order they were so supposed to hit their bell but at the timing was entirely up to the individual. They had to listen to the sounds of the room, be in the moment, and then strike their bell when they saw fit.

I think that Blossom really relates to Hip Hop Ni Sasagu. Blossom was a response to the story of the Jena 6 in Louisiana a few years ago. I am sure that you remember the racial conflict that started when a black student asked for permission to sit under a tree that was normally occupied by white students. The following day there were nooses hung from all over that tree. The trees is an elemental form that I have used several times in work before, I find the associations that can be generated from it so lyrical. In the East, underneath the Bodhi tree is where the Buddha finds enlightenment. In the west, lynching is a vestige of our collective American history. On the one side you have the tree of life basically and on the side you have the tree of death. Certain African cultures see the tree as the crossroads to the afterlife, yet a third perspective. I wanted to create an artwork that was also an experience, at once tangible, tactile and audible. Blossom is a life-sized tree constructed in the gallery with a piano emerging from it. The piano has been converted into a player piano, and being a musician myself, I programmed it to play my own improvisation on the Abel Meeropol and Billy Holiday standard "Strange Fruit".

The idea started as a drawing but with the support of Grand Arts in Kansas City and some very knowledgeable consultants, we were able to retrofit the baby grand into a functional player piano, where the keys and pedals still function.

Just asa Jazz musician may cover a musical standard, artists often "cover" art historical and visual standards as well. Of course, in both cases they must claim it for themselves by changing it. Blossom's Strange Fruit follows the basic chord progression of the song but with different alliteration and more of an improvised melody. If you are really familiar with the song, you can catch it, but at the same time it sounds more like a searching and elegiac improvisation of the original.

The only limits are those you impose on yourself.

Posted by Arcy Douglass on May 15, 2009 at 22:00 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |