|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Interview with Laura Fritz by MK Guth  Laura Fritz at NAAU, photo Jim Lommasson MK Guth: I wanted to start with the basics like, what is your background? What brought you to art? Where did you go to school? Where was your area of focus and does that connect to how you are making work now? Laura Fritz: Well, I grew up in the Chicago area and I started out being really interested in lights in darkened rooms. They fascinated me. Sometime between Preschool and Kindergarten age there was this one grocery store that had an aisle where the lights weren't working. It was the peanut butter and jelly aisle and all the jars were just glowing because the aisle next to them allowed light to come through the side. I would just run up and down the aisle because I thought it was so interesting.

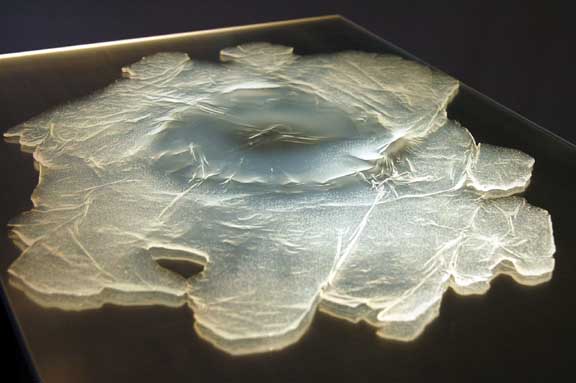

Laura Fritz, Illuminant (detail), 2006, photo Sarah Henderson I'd also set up haunted houses in my cousin's bedroom because he had all of these cool light up Star Wars toys and I'd lead people in one by one to look at all of the different displays. And I also did a lot of drawing of 2-D things so when I went to college I ended up studying painting, but I also studied jewelry as well. MK: Where did you go to school? LF: I went to Drake University in Des Moines Iowa. I was a painting major and one of the things I found was … we did a lot of still lives. Through learning those fundamentals I realized I was really interested in the spaces between the objects, rather than painting the objects themselves. The more time I spent there the more sensitive I became to the placement of objects and the way they worked together. That and the moods the different configurations create. Also, I spent a lot of time in the jewelry studio making objects, some with strange telescoping parts and dark patinas. Eventually, both interests kind of came together with the installations where I place objects in the spaces I create or tune… in the case of larger scale situations. I often make dark mysterious spaces with elements that are lit to enhance the viewer's fascination or the mysterious qualities of the experience.

Laura Fritz, Origination (detail), 2003, photo TJ Norris MK: So that does connect and function with your early experiences LF: Although I didn't realize that I could use installation when I was younger. I didn't realize that sort of thing could be art, because I was brought up to believe that art was drawing or painting. Installation art wasn't something I encountered until college and I started looking at people like Eva Hesse. But I didn't really start doing installation art until I moved to Portland and took a few continuing ed courses at PNCA. That's when I got my first solo show at the Manuel Izquierdo Gallery from Nan Curtis. MK: What artists influenced you? who do you like? LF: Donald Judd, Robert Irwin, Eva Hesse, Hieronymus Bosch and de Chirico are influences and I like Smithson's mirrors, some of Louise Bourgeoisie's works, Willem Kalf and Larry Bell.  Giorgio de Chirico, Mystery and Melancholy of a Street, 1914 MK: This notion of mood and the space between objects that you've spoken about relates to the installation you have up now at the New American Art Union… there is a very particular mood in that gallery and when one is in it you are just as aware of the space as you are of the objects in it. The objects highlight the space to the point where everything becomes the piece and not just markings on the wall that are created by the light reflected from the box in the center of the room. In essence, all corners of the room are opened for investigation. It's a dark, foreboding and uncomfortable mood. Is that how you see it? And can you describe the piece and its title?  Evident installation view NAAU, photo Jim Lommasson LF: Well the title of the piece is Evident, which basically gives out as little information as possible while cuing the viewer that they are going to have to take an investigative attitude. It has a sense of humor too, because what is Evident in the room is so not obvious. MK: Do you want to talk directly about the piece? LF: It is about perception, anticipation and expectations. The room is dark and as the viewer moves into it you are trying to get your bearings so you start at the first element which is a table. The table has its top split in two and inside the gap there are mirrors and several objects that one can only partially make out because the top is only partially open.  Evident (installation detail) photo Jeff Jahn Then you move onto the middle of the room which is where the object with a projector in it is. That box projects insects on all of the walls intermittently so that the viewer might only catch glimpses of activity. Meanwhile while you are looking at the lights, there is a large empty cabinet at the end of the room that has a foreboding presence. It's dark so you are only aware of it when you are nearby and its posture and placement in the room suggests a dark figure in the background. As you come up to it the door is partially open so you can peek inside. When you look you might expect that there is something in it, but inside it is just black. There is nothing to see there, just space. That space has a feeling about it as if that space were an object or a presence. Actually, I deliberately made the cabinet about as tall as a person so that it would feel like an authoritative, watchful presence.

Evident (detail of insect) MK: And the light on the wall? LF: The reflected lights on the wall have very intermittent activity and a lot of times you won't see any insects at all but you will catch something out of the corner of your eye or the insects dart through very quickly or eventually you will see an insect just sitting for a while. And there is a real surreal quality to it because it is winter now and the bugs are out of season, normally they would all be dead. MK: You mentioned at the outset that your work is about perception and anticipation of the viewer but really you kind of deny the viewer the grand reward. So there is this anticipation that something is going to happen and a little glimpse from the light box or the reflection up on the walls you see one bug but there is this sense that there is something more to come. You set up this situation for the viewer where they anticipate something to come but then you deny it because there is no big reward and the gestures are very minimal and subtle. Is that a strategy you use in your other work? I'm sure it's purposeful. LF: Well it is purposeful and you can look at it a few different ways. You could see the cabinet as empty and it isn't giving up any of its secrets or you could see it as an opportunity to wonder and question, is there really nothing in there or is there something in there intermittently just like the video of the bugs? It calls into question our beliefs and powers of observation. Or is the presence of the space actually the reward? MK: In this body of work and your other work there is this hint of science, like a faux laboratory. Where did this interest come from? LF: Actually I'm very interested in how people figure out or explain what is going on around them. Basically figuring out the unknown and the scientific method is just that, using experiments in very deliberate and controlled ways to try and answer questions about what something is or why certain things occur so they can make predictions about what is going to happen in the future. So I like to play with that methodology and strategically disrupt it. MK: So are you mimicking the aesthetics of the laboratory, does that come into play in your work?  Evident (partial installation view) photo Jim Lommasson LF: Well it does in a way, I like to be just suggestive of it so the viewer can feel like it is kind of a laboratory but it still doesn't have 100% of all the elements of a lab. Instead of the illusion of a lab, I design the furniture so they aren't completely identifiable and the proportions are somewhat uncomfortable or suggest a different agenda. A real lab is a working environment and there is a stillness to what I do that implies something else. MK: Kind of like the Frankenstein laboratory a little bit because you don't know what is developing and it has this fantastical element. LF: Right, it looks like a laboratory that is not to code, so you never know what is going to happen. MK: There is this whole value to that type of conversation because it is the unknown. Because of the setting you don't know if something is trapped in the box or under the glass and that often comes up in your work. There is something about it that is very visually captivating but is also simultaneously unnerving or disturbing.  Interspace (detail) 2008 You mentioned to me previously that with a previous piece, Interspace (Quality Pictures, 2008), somebody tried to release the cat that was projected walking around above the viewer in a false ceiling you constructed. Is that something you encourage or a response that you are interested in from your viewers? LF: Well I'm interested in strong viewer responses but I don't necessarily want them taking apart my sculptures and installations physically. But it is really interesting that what I do is kind of like an experiment on the viewers. I mean, there are a variety of responses. Some people have been more apathetic, just merely observing and some people are more empathetic and concerned whether the cat is being fed, they are convinced it is alive. That is when a few people have tried to go in or they were just trying to figure out how it was put together. I keep my designs very simple and elegant but they require a great deal of precision so if someone tampers with one I have to recalibrate it. Then there are people who try to test the animal's response by tapping on the plexiglass and waiting for a reaction. If they see a motion at that time they often interpret it as a response to their action, and therefore the animal is alive and real. Scientists call that apophenia, a false positive. There was another piece called Transposition. It's a box that was on the floor and within it a cat is projected as if it is moving around inside the box. MK: You showed that at Audio Cinema for the Portland Experimental Film Festival's video show (2007)? LF: Right, That's one place I have shown it. It has milky white plastic on one end and a series of ventilation holes on the sides. The way the cat image moves across the plastic and throws spatially corroborating shadows through the ventilation holes in another direction really looks like there is a real cat inside. The cat is sniffing around, tapping things with its paws and testing the borders of the box. Essentially the piece uses the normally flattening process of making a video to make a three dimensional Transposition of the cat and the space it is exploring. It's really believable and I've watched people watch it and sometime people will test it to see if there is really something in the box. MK: Back to the earlier notion of a science lab and Shelly's Frankenstein, do you read a lot of science fiction literature? LF: Well actually I don't get very much time to do a lot of in depth reading but I did start reading many chapters of Frankenstein and scanned Lovecraft's Reanimator when I was looking for titles last summer. Despite that, I ended up coming up with Evident on my own. MK: I have a quote by Elizabeth Pence about your objects in your Seattle show…. In it she wrote about, "linkages to a validating sphere of knowledge, they exist as hollow signifiers of scientific industry and may exist in an aestheticized realm as a false archive." Do you connect to that? Because she seems to be going back to this notion that you are creating this scientific archive… a cabinet of curiosities of sorts like the museum of Jurassic technology? LF: I'm really not setting out to make something that looks like an archive of science, which might imply science from a certain era but of course it's a valid observation about the work. It is put out there to spark people's various interpretations from their own experiences rather than something specific from mine. I might tease and suggest an archive in the most basic sketch of the word, so you could see it that way or maybe as a fungus you just found in your fridge. It can even be more personal like something you discovered in the landscape or more scientific/historical things. People project their interpretations and it's why some people really connect with the work. The work is very porous to interpretation because it has been divested of everything but the necessary details, which leaves room for the viewer. MK: This plays with the notion that you are pushing the psychological effect on the viewer. That you are toying with our ability to believe or our desire to believe. LF: Well one of the things that I have noticed about religion is that people use it to explain and comfort themselves about the unknown and that kind of intersects with science as well. I'm interested in the areas where people are more uncomfortable with the unknown, the choices or mechanisms they use to interpret open ended situations MK: Hm, it doesn't feel that open ended to me. LF: Really? MK: It feels like you are asking the viewer to choose what they desire. To choose their notion of what they desire to be real. But I guess it is open ended in that the viewer has to make the choice. LF: That's what I mean by open ended as far as interpretation goes, but I do create a scenario that compresses and intensifies the viewer's experience. MK: You spoke before about psychology in your work, do you want to talk more about that?  Interspace (installation view) 2008 LF: I'm playing with the type of reaction that people will have. One important element is empathy. Several of my videos have looked like an animal, insect or cat, is in some kind of confined situation where the placement and the size of the enclosure effects the level and the kind of empathy a person will have. In some cases the animal is in too small a space to be comfortable log term, or that they might imply they are being held against their will or like in an installation like Interspace they are definitely comfortable. The body language of an animal, the work's position and the size of the enclosure are really important. MK: That is a huge part of what you do, like in the Interspace installation with the large false ceiling… that cat shouldn't have been up there. By the way, who is the star of the videos with cats? LF: Transposition and Interspace were Sid, the black cat who was just sitting here. He really loves boxes and the sets I use so it's a big game for him, he always wants to get involved. MK: Insects are much different from cats though because they generally aren't pets and that makes us more uncomfortable. We are less empathetic and have more fear than with insects than with domesticated animals. LF: Well I think with Evident the insects are surrounding the person on all four sides so it's almost like you are in the place of the cat from Interspace. In Interspace the cat is engulfed in space and the viewer is watching it explore. In Evident you are moving around looking at the space and you are surrounded by the video, which generates an enhanced sense of space. MK: So we are the cat? LF: Sort of, but it's not the same MK: Because we are not being watched, unless you have hidden cameras? LF: No cameras, but I do watch the viewers and even without me actively doing that the cabinet is analogous to another human presence in the room. MK: It has been mentioned by other writers that there is a connection to minimalism in your work. What is your connection to that work? Do you connect yourself to minimalism? LF: Well I really love minimalism but I don't call myself a minimalist. Apparently a lot of other people have connected me with minimalism, but I just prefer to use an economy of means. I don't want to use any more elements than are absolutely necessary. Extra elements are just fluff and they weigh down the essence of the work and make it less successful.

Donald Judd, Untitled 1976-1977, Des Moines Art Center When I was going to college I would often go to the Des Moines Art Center. There was this one Donald Judd piece that I loved, Untitled 1976-1977. It is comprised of rows of stainless steel boxes, many of which had diagonal interior surfaces tilted at different angles. Also the way they had it displayed was right under a skylight so it reflected the sun. I really appreciated the mirroring and the way it handled the light. I also spent a lot of time looking at the Robert Irwin disk, which had four lights on it. Those two works were basically using light as an object. MK: So you wouldn't describe yourself as a minimalist, how would you describe yourself? LF: I would consider myself as more of a director because I organize elements for a certain effect upon the viewer. Like at the New American Art Union I'm using light effects, the spaces between objects and the subject matter of the insects all to create a mood. MK: What about your relationship to the fantastic? I mean there is the legerdemain or slight of hand that tricks the viewer. Or you have something like your Reed show, a curio cabinet full of wonders that one can't quite get to. Your installations seem like something we know, they are canny in that way but not completely.  Caseworks 13 (detail), Reed College 2007-2008 LF: Well I do like to play tricks on the eye, like the table with the opening and a mirror inside in the current show. I'm playing with the depth in the table. If you are looking from the top downwards it is bottomless almost, but then you are seeing the ceiling in it as well as your own face and also the specimens. People have written about how the table has two specimens, but it has four. If you are very thorough and tilt your head down you will see three but the fourth one is nearly impossible to see… you can do it only from the corner of your eye. It is almost like a test of one's powers of observation and another layer of mystery. As for the fantastic, I'm definitely interested in what is strange and of the other but it's never as literal as specific monsters or science fiction. MK: So it is not fantastical, it is mystery LF: Possibly but because nothing in the show is something you can quite identify decisively… MK: It's mysterious LF: But I do have an interest in the fantastic, but whether I put that straight forwardly into my work in any identifiable way is another question. MK: There is this otherworldly aspect though, because at the New American Art Union you have transformed the gallery and you don't feel like you are going into a traditional exhibition space at all. With the projection and the objects there is this otherworldly aesthetic and a sense of logic behind it. LF: The fact that I have insects in there alone changes things. Those are summertime insects in the middle of winter, which have an otherworldly out of season effect and something I was very conscious of cultivating. The installation objects transform the space and the space in turn transforms the objects so they kind of mirror each other's influence and it has an open ended yet complete feel. MK: So what's your process? LF: Typically I have something in mind about a certain type of experience I want to create or I have a specific idea about a video or object I want to create and I basically experiment in the studio. Like with Evident I made a prototype of the box, actually several different versions of it to determine how it would work in the space so the process of making the work is like I'm in a lab. MK: That definitely fits in with your methodology LF: And also with the objects that I make, I call them specimens… I basically experiment with several different types of methods, materials and castings and I do pretty much have a scientific method for testing it out where Ill do a specific casting several different ways with very slight differences… because I want to understand how they operate and what effects are maximized or minimized with each differentiating variable. For example I'll cast an object with a clear resin and then I'll add or take away elements like color or particles that make them more opaque or luminescent. Eventually, I set out whole arrays of them out on a work table so I can figure out how they interact with each other. MK: What do you do with your spare time? (laughs) LF: Spare time? Well I do go for a lot of walks, I like to cook and I'm very into gardening. I like to go to nurseries and try to find the strangest plants and see how they grow. MK: Cooking is a lot like the lab. LF: Actually I've done some experiments with cooking too. MK: How so? LF: Ive made different spice blends or different recipes using an empirical process. Like just for gingerbread I've used two different kinds of molasses and different kinds of sugar and tried to make the darkest dark gingerbread or the lightest and everything in between. It is a testing process. MK: Is there a goal to find the perfect gingerbread? LF: Not really, just to find out what different kinds I can come up with… finding the extremes. MK: So your pastimes are other kinds of experiments whether it be the kitchen or the garden. Where do your titles come from? LF: Actually, it's the last thing I do, and I only title them because I think leaving it untitled would be more distracting. I try to make them succinct as well as both vague and specific at the same time. Typically that means they sound vaguely scientific because I don't want to draw too much attention to the titles. I'm more interested in the work itself. To me it's the way the viewers experience the work, instead of having to read about it. MK: You don't want a didactic experience LF: I just want people to experience their own perception Evident is on view at NAAU through February 22, 2009 Posted by Guest on February 14, 2009 at 18:00 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |