|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

An interview with Glenn Adamson

Leading craft writer, researcher, educator and theorist Glenn Adamson is the Author of Thinking Through Craft an introduction for artists and craftspeople dealing with the common perception of craft. He will be giving a lecture entitled Craft in the 21st Century: Directions and Displacements Saturday, Feb. 21 for more information check out the Museum of Contemporary Craft's events calendar.

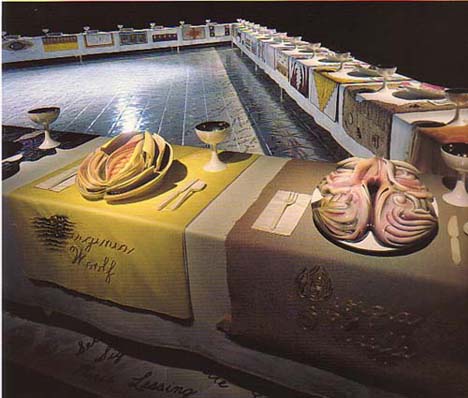

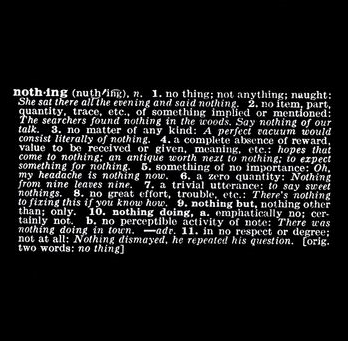

Glenn: To be honest, not very, though it looks great. A cynical observer might say this is an indication of what an art and design historian looks for in a crafted object. Glenn: I always say that craft is exactly what you think it is - that is, if you have a definition that's not pretty close to the proverbial person on the street's, you are probably barking up the wrong tree. So, something like "knowing how to make something, through a detailed engagement with materials and process." Notice that doesn't include "by hand," nor does it presume that craft involves making something functional. Alex: How can something not be crafted "by hand?" Glenn: The British theorist and woodworker David Pye pointed out that almost nothing is crafted by hand - pinchpots and coiled baskets, and that's about it. Craft involves tooling. Pye ingeniously introduced the division between "the workmanship of risk" and the "workmanship of certainty" as a way of analyzing that tooling - a craft process involves a lot of risk and manual control, and a very automated process will produce the same result every time. But this is not an absolute distinction, it's a matter of degree. Furthermore, you could argue that many processes (from slipcasting to computer-aided design) combine elements of risk and certainty in ways that distribute the imprint or features of craft skill across a large number of identical objects. And we haven't even gotten on to issues like repair and forgery where craft is employed in order to make an exact replica of a previously existing object (which may itself have been mass produced). What it adds up to is that you can't easily distinguish craft processes from non-craft processes; craft is present in most activities of making, but in many different forms. Alex: Why do you think craftspeople should care about their secondary status to art? Glenn: Because it is the condition in which all craftspeople exist, whether they like it or not. Art can be crafted, of course, and it often is. So I would not (at all!) say that art and craft are distinct categories. What I would say is that much art tends to hold itself apart from "mere" craft. This often involves attributing to it certain qualities - femininity, ethnicity, non-intellectualism. That is upsetting but it can also be turned around and made into an instrument of critique. Glenn: No, not at all. Craft is as susceptible to use by avant gardistes and conservatives alike - it's not a matter of red state/blue state (that always makes me think of Dr. Seuss, by the way). The arts and crafts and studio craft movements were both strongly divided by conservative and progressive impulses. It is important to know about its history of conservatism in craft, though. Many people think craft is intrinsically humanist and liberating, but the totalitarian powers of the twentieth century - in Japan, Spain, Germany and Italy - all found it to be a useful basis for propaganda and rhetoric. Alex: Would you say that there is a similarity between Dante's Inferno and the craft movement from modernity as the arts and crafts movement to present craft? Glenn: What a fantastic question. I'm not sure I can improve on it by answering it. But you know a bookseller in Italy once complained to me, when I was buying an English translation of Dante's Inferno, that Americans only read that one (and never Purgatorio and Paradiso). He was certainly right in my case. Maybe contemporary makers need to read Karl Marx, not just William Morris.

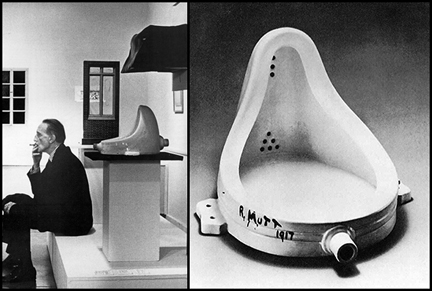

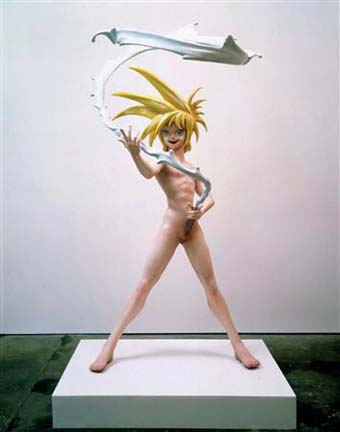

Glenn: Those are three very different cases but they do have one thing in common: the appropriation of other people's craft skill. The historian Ezra Shales has recently pointed out that, given the methods of sanitary porcelain manufacture at the time, it's likely that Duchamp's infamous Fountain was actually a handmade (or at least hand-finished) object. Warhol and Hirst also operate through the hands of others, by and large, rather than making work themselves. Many find this distasteful but I don't see craft as any more or less important within a work if the artist isn't the one doing the crafting. John Roberts has written an important book about this recently called The Intangibilities of Form, which I highly recommend.

Glenn: Did I say "concept is craft"? If so I didn't mean it. Craft deals with the physical. It is a big arena of practice, but lots of things aren't craft - I don't think objectless disciplines like music or dance or surgery are helpfully grouped within artisanal practice, for example. And there are terms that are held to be directly opposed to craft, notably industry and fine art, as well as kindred but distinct terms like design. Craft turns out to be implicated in all these things (on factory floors and in the making of modern sculpture for example) but to understand the nature of that implication, we must remember that it takes place within an overall structure of opposition. Glenn: I use that example in the book too - in the context of a discussion of Derrida's conception of the supplement. Long story, but basically the supplement is something that is necessary to an art work (or other text) but is taken for granted or ignored at the point when the text is 'read.' Written language is the ultimate example of this - we 'forget' that we are reading a material object when engrossed in a novel - but a musical score is another good instance of the principle. So there is something structurally similar in the preparation of a score and, say, the weaving of curtains for a room, which also might be considered supplemental. But otherwise I don't think writing music is much like a craft; the product is a sound (or a supplementary trace that allows the future production of a sound). To me craft produces material objects.

Alex: Do the ideas of Pastoral and Conceptual craft work agents each other in contemporary craft? Glenn: I don't really believe in something called "Conceptual craft." I think the term "Conceptual" is best reserved for the conceptual art of the late 1960s and early 1970s, which by the way was explicitly concerned to eliminate crafted aspects of production (in the hopes of more closely approximating what Joseph Kosuth called "Art as Idea as Idea.") That's not to say that craft isn't a way of thinking through ideas - and "the pastoral," a refusal of the mainstream, urban, and empowered - is a good example of that. Glenn: Fortunately those two things seem to be pretty close together. I would like to see craft set free of both its embattled mentality - "we are the craftspeople and nobody respects us" - and its presumption of moral superiority. If you take together developments in contemporary art and design, in which production values are very much at the forefront, and he DIY movement, in which "crafters" young and old have taken up various amateur activities as a means of self expression, I think you begin to arrive at something like this state of open play.

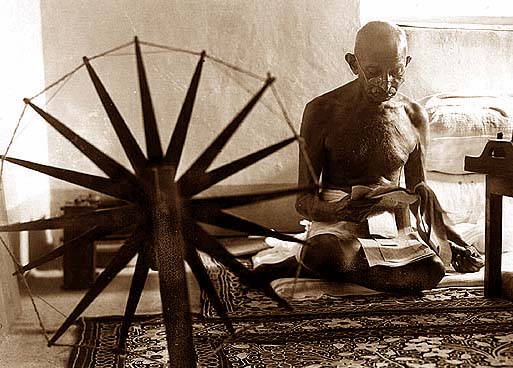

Glenn: Since I regard modern craft's history as marked by tremendous diversity, and resist any attempt to reduce it to an essence or a "typical" condition, I would not want to say that any one person exemplifies modern craft. But there are certainly people who exemplify particular configurations of modern craft, and who capture your attention if you are interested in that history. Just to stick with the twentieth century, a good list might start with Mahatma Gandhi, Soetsu Yanagi, Gio Ponti, Peter Voulkos, Aileen Osborn Webb, Judy Chicago, Jeff Koons, Alison Britton, Dale Chihuly, Ai Weiwei, and Takashi Murakami. Alex: What object did Gandhi make to mark him the first person off the top of your head? Glenn: The famous example is Bourke-White's photo of him at a spinning wheel. He was interested in encouraging Indians to become autonomous, so that they could throw off imperialist control of their country and survive without mass produced imports. This involved much more than craft of course - mostly I think he was worried about food - but being able to spin the thread that would be made into clothing was also important. I like the example because it shows that even in a cultural context that is very different from America's industrialized, capitalist, individualistic, and imperializing history, craft can still be used in a manner that is simultaneously symbolic and economically implicated. Alex: Is there current hot spot for craft? Glenn: I have been very impressed with what is happening in Scandinavia. You have lots of government funding, a young scene where the curators and artists often went to school together, and great opportunities for exchange. It's a place to watch.

Glenn: You know, it probably does. But for some foods, you really want plastic. Alex: I guess you do. Thank you for your time and I look forward to you lecture. Posted by Alex Rauch on February 17, 2009 at 6:00 | Comments (2) Comments That's a wonderful interview Alex, great questions... PS Koons' Lifeboat is at PAM right now. Posted by: Double J Very engaging interview. Posted by: margaretross Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)