The Portland Art Museum's latest show, Wild Beauty: Photographs of the Columbia River Gorge, 1867-1957, is more than just an exhaustive photographic history of the Columbia River Gorge, it is a bittersweet reminder of the fragile beauty of even the most rugged environments. The show's message comes across as if one were watching an unbiased world news program presented in a straightforward manner, as a chronicle of time passing into memory.

This archive exists as ethically-subtle dialect between natural beauty and industrial advancements is the underlying current that drives the show; both the natural and industrial aspects are cultural icons that correlate with current issues of international debate. As such, the photographs of Carleton E. Watkins, Benjamin A. Gifford, Ray Atkenson and an unknown photographer(s?) from the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers are key narrators in communicating the nostalgic wonderment of a Columbia River Gorge we will only know through facsimile.

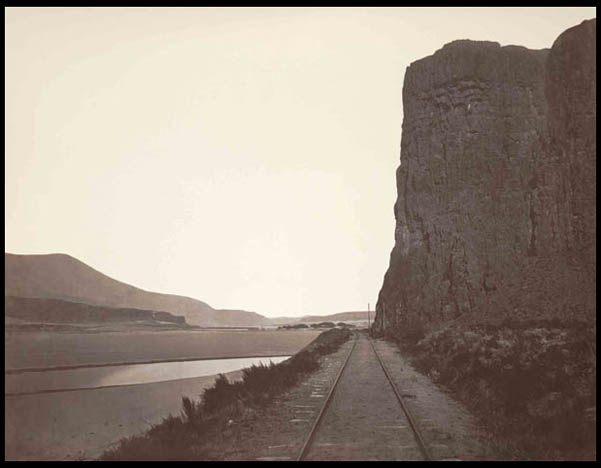

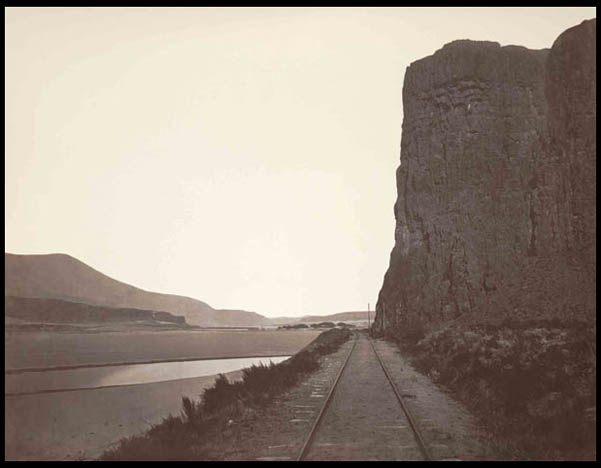

The first room introduces one to the wet collodion process (via a video), surrounded by many of Watkins' Mammoth Prints, a few of his stereographs lining the walls and a large print book of mammoth print on a pedestal. On the right cusp of the second room is Cape Horn Near Celilo, Columbia River, 1867. This subtly composed Albumen Mammoth print by Carlton E. Watkins is hung at eye level placing the viewer directly between the train tracks, which disappear around Cape Horn while the Columbia River unfolds into the distance. His manipulation of perspective helps develop a lusty visual angle on the idea of Manifest Destiny. The angle enables an enticing control of the untamed wild; Watkins turns the train tracks into a metaphorical arrow, encouraging continual expansion of Manifest Destiny. The composition is coupled with its wide range of tones can be seen as a preconception, or at least inspiration for Ansel Adam's zone system. Watkins eye captures an unprecedented level of photographic elegance and an early stage of development in the Gorge.

The largest room on the second floor is home to two particular pieces; a mammoth Camera on a pedestal and Benjamin A. Gifford's Celilo Falls (1899). The mammoth camera, though not as large as Watkins' mammoth camera, demands respect by reminding the viewer of the incredibly large and cumbersome tools that early photographers worked with. The small mammoth camera on display allows the viewer a better understanding of the labor-intensive process and technical manipulation required of the photographic pioneers in capturing every photograph they wanted, good or bad. Without this display, one lacks the reference necessary to compare the technological advancements that lead to today's era of point-and-shoot camera phones, auto-focus facial recognition and other photographic developments. The display makes it easy for one to imagine the labor of moving a camera that large when compared to the 5 megapixel cell phone in-pocket, and one cannot help but be impressed. The camera mirrors the creativity and engineering that was fervent in the Columbia River at the time.

Behind the mammoth camera in the large room is Gifford's Celilo Falls, (1899) an enlarged gelatin silver print. In the foreground is a small figure standing alone on some rocks among the raging edge of the falls. This image narrates through its composition the advancement in accessibility within the gorge and in photographic technology during the thirty-two years since Watkins' first trip to the Gorge. The photo installed here has a brown wooden frame and is the largest print in the room. In this image, Celilo Falls is dramatic and awe inspiring. It is as if Gifford has composition is almost horizontally symmetrical, the visual lines move one's eye and the photograph's location and magnitude are indicators of the technological advancements in infrastructure and photography.

In the second to last room is a mix of both vintage and modern prints. This dichotomy of modern verses vintage is particularly intriguingly subtle subject - as such, it is necessary to undertake a brief tangent on Ray Atkeson's Confluence of Deschutes River, 1940. It is a modern ultrachrome pigment print from an original kodachrome 4x5 negative. This photo is old enough that oxidation has occurred and altered the image's color so much that when the image was scanned it went through a color correction process. A professional color correction dialed in as closely as possible to look like a new kodachrome print of the time would. However, upon close examination there seems to be something slightly odd about the colors and ultrachrome texture. They seem to be created out of millions of tiny dots. While impossible to notice at digital scan level and it really isn't noticeable in a photograph of the photograph without extremely close examination, there seems to be a difference because film has grain, not pixels. As such, the photograph really doesn't have an era in which it belongs. The photo has a textural feeling much like that of a print dating from the 70's that would be more at home in a bowling ally, and there is a strange visual dialectic that occurs once one is aware of this. What would the original negative look like unaltered? The topic of color correcting modern prints is a bit of a stretch from the 90-year era of technological advancement, but the point is vicariously mentioned in the show and is worthy of discussion because it effects what all historical photography and all film photography will become eventually. Even in the future, printing and facsimile processes beyond photography will become more advanced and nostalgic representation is an important fraction to understanding the historical imagery. Atkeson's kodachrome negative photograph is one early example of an original color photograph of the Gorge, showing how technology moved past hand tinted gelatin silver prints and onto color.

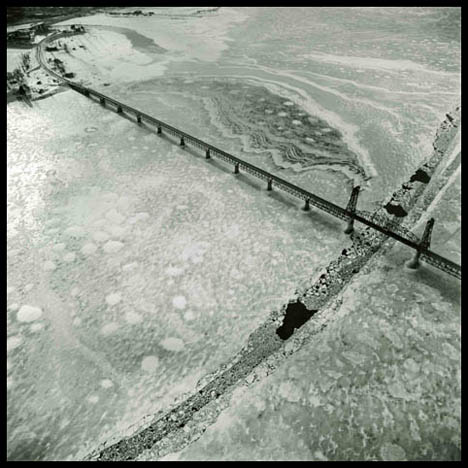

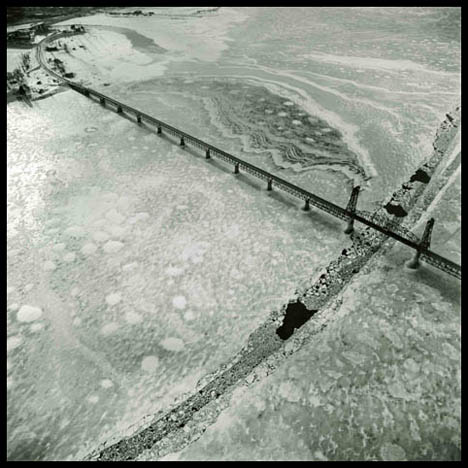

The most striking photograph in the entire show is Hood River Bridge, 1950, by an unknown member of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. This anonymous aerial photographer captures the landscape both as a document and an elegantly composed photograph. A simple "X" is created by the Hood River Bridge and a line of broken ice floating in the Columbia River from barges forcing their way through. Both lines of the river and the bridge are pure black and the meeting point of the two is located in the right central third as the river and bridge head directly to opposite corners of the right side. This artist's work is so virtuosic that he is one of the most represented artists in the show behind Watkins, Ladd and White. As time has progressed aerial photography became more commercially viable.

The show ends with the simultaneous triumph of The Dalles Dam (hydroelectric power) and the submergence of Celilo Falls. It immerses the viewer in multiple cultural-economic eras through; albumen mammoth prints, modern digital prints, 1950's aerial photography. The images vary from wild to industrial, ephemera to existence and as Wild Beauty radiates tones of natural fragility and the trends of ephemeral technologies. As such, the exhibition is beautifully sweet in its development of photographic elegance, but deals a bitter end where one is left dreaming of the aesthetic pleasure of the past as we contemplate the future tradeoffs of industrial development.