|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

Jonathan Lasker at PAM

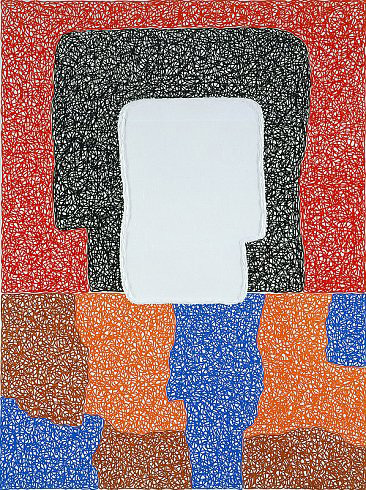

Jonathan Lasker is a painter's painter. His work has answered the call to move and change and be something relevant during an era when the medium of paint was pronounced dead. Lasker's oeuvre speaks to the notion of possibility and invention within the ideas of material and symbol while speaking to the experience of this time as well. Over the last thirty years, Lasker has distilled this language into something almost audible, wrought with the eloquence of a haiku. I had the opportunity to speak candidly with Lasker about his life's work at the Portland Art Museum, where his work will be on view until January eleventh. PORT: Do you see a great disparity between the east and west coasts? JL: It's not so great as people think. There is a different temperament of course. New York has a very particular environment; it's a very driven environment, very work-centric. I think that Los Angeles has a slower way of life. Because of the great distances between places there, people are always in their cars, and that creates a bit of isolation. San Francisco and Portland however have centers which is more comfortable for a New Yorker although the pace is slower. Generally the ways of life are different, but the art issues are not so greatly different. PORT: Do you see any difference in the art being made on the east and west coasts? JL: In touring this museum (PAM), what was interesting was that I saw a lot of things that I had seen living in San Francisco years ago. I had gone to San Francisco after graduating from Cal Arts. I lived there for about a year and a half, and there was quite a bit of painting that I saw there, in the galleries and museums, that you don't see in New York at all, like some of the Abstract Expressionists from the fifties. These painters were second generation Abstract Expressionists that would be exhibited in California but that wouldn't be exhibited at all in New York. So it was kind of nice to see these paintings again from artists like Edward Dugmore, or Hassel Smith, or Joan Brown. These are artists that people in New York really barely know. So in this way you can see that the East and West Coast have slightly different histories. PORT: It is always surprising and interesting to me to realize the actual strength of geographic influence when you are making things and associating yourself with a community of artists. I wanted to ask you about your thoughts on the climate of painting now as opposed to when you were studying painting at Cal Arts. Having had to answer to Minimalism's manifesto and the cries in the streets that paintings was "dead", what kept you painting as opposed to joining the bandwagon of the then current trend in both theory and art making? JL: Which at that time was Conceptualism. At Cal Arts, to be a painter meant you had to take a stance, because there was a very antagonistic attitude towards painting there. In a way it was good for me, because it forced me to shape my reasons for making paintings. It also forced me to make paintings that had reasons for being paintings. So I think, in a way it pushed me in a good direction, although the experience was alienating. PORT: Do you still feel that, in a sense, this attack against painting? JL: When you get such a strong push coming from one particular position like that, it stays with you for a very long time. Then all of a sudden, one day you wake up, and realize the war is over and painting has won, if only by maintaining the sovereignty of its borders. Yet still you feel like that last Japanese soldier who's out in the jungle, and he thinks that WWII is still on. He's hiding in a cave, waiting there for the next attack. (laughing) In the seventies, you had to defend painting, and you had to defend it in the eighties as well. Yet the issue isn't so pertinent today, really, because I think painting now is thoroughly accepted as having a raison d'etre. PORT: Yes, despite the age of technology and the trend towards digital media. I wonder how you see these works in relation or response to the age we live in now? JL: You know, I began this body of work in the late seventies, which was before the age of the personal computer, or before it was widely available, before Macs were in every household. I personally have no fluency with visual software, such as Photoshop. I'm really rather computer illiterate. However, I am told that these paintings relate to some early visual programs from the late eighties. As such that you might make images that would have some of the mechanics of these paintings with those programs. PORT: Do you think of this as a sort of zeitgeist that seeps into what you make or do you consider it more of a coincidence in the occurrence of developing one's own language in any time ? JL: I consider it more of a coincidence, but there was a zeitgeist propelling the work to some extent that made me pick up on certain things and certain issues, certainly as they pertain to painting. Particularly if you talk about painting and the pertinence of painting in the 70's and 80's. At that time, for me, the painters to beat were the Minimalists. For example, for the Abstract Expressionists, it was Picasso. Picasso was the painter to beat. It wasn't really as if I was trying to beat the Minimalists, but the Minimalists were an endgame. They were part of this whole push towards making the last possible painting. Ad Reinhardt was involved with that, and Stella, and then it reached a zenith with Minimalist painters. For me, the issue was how do you paint back into subject matter, yet at the same time have a picture which is self-reflexive; one that tells you what it is as a painting. One that stresses painting as a material object, yet also has a metaphorical condition within it. And that was what was interesting to me, to have both material reality and pictoralism. PORT: The thing that I find so interesting about this argument is that there is a personality to the forms within the paintings. The objecthood of these pieces seems to allow them to have more of a pronounced voice and more of an individual identity. They become sort of referential unto themselves. Granted there is the criteria we have for pictorial space within a painting, yet there is also a suggestion of metaphor. I wonder if you could talk about that. Do you feel as if these paintings move beyond that, or is this the conversation and space you are wanting to solely inhabit and investigate? JL: The idea of the dichotomy of the work being both the thing unto itself and also reflecting on a metaphorical condition has always been the primary goal. But then there is always a lot of other subject matter that comes into the paintings. A lot of visual vocabulary and discursive themes. There is the idea of the hand. And also the idea of automatic mark making, yet automatic mark making with preconceived boundaries within the form. One does something that is a random mark, yet has a finite definition of what it will be used for in a pictorial function. There is also something of creating a perfect matrix in the background and marring it with a mark, thereby being invasive into that system. That is another thing that was part of my intention in the beginning. At the time people would look at the pattern paintings that I had painted before I put the figures into them, and they would almost beg me not to invade that perfect surface. PORT: Do you set up these conditions for yourself, always, as limits or rules? JL: There are not limits or rules. But, I knew when I painted "Reason and Free Will" that I wanted to do a background as something like that (gestures to the painting "Reason and Free Will") where there would be a shadowy shape in the background and a kind of horizon line and then these forms that seem to create puzzle elements, and so I drew up to those boundaries and created those shapes.

PORT: Do these shapes ever become too referential so that they cross over too much into one realm or the other? What I mean to say is, does that dichotomy between objecthood and metaphor ever become too lop-sided for you? JL: That is a danger that I watch out for. I try to keep it from becoming so defined that you can actually see an image. PORT: I also wanted to ask you, because all of these paintings here do have such a pronounced 'horizon' line, Why the horizon? Why not the sky? Why not an aerial depiction? Why is it the bottom edge that you choose to ground these in ? JL: Well, because I actually am trying to find pictorial space. These pictures are really referring to traditional pictorial space, and they're not diagrams as such. People often look at them as almost being diagrammatic. People can become puzzled by these pictures and have difficulty finding their way to reading the space in the pictures because they are intended to be ambiguous. In speaking with Bruce Guenther about these paintings, he very clearly saw horizon lines in these paintings, and I believe you do as well. Yet often they are seen as being very flat and not having any particular spatial reference. I try to bring this forward as much as I can without having literal perspective. PORT: Does this determine your color choice at all, wanting to sort of trump this pictorial space without destroying it? JL: I often think of natural light in these paintings. For example, these scribble paintings have some relationship to Impressionism, I think. There is almost an Impressionist light in them. It's the way the brown plays against the orange and gives you kind of a chiaroscuro, and then you have the complementaries of the blue against the orange. But it is the white which also gives you the backlight and the forms become as light or as dark as they are filled in, so there's a mathematics to the amount of light that you have. You are working from the positive of light to negative colored-in forms. PORT: Does the color choice ever have a more philosophical bent? Is there ever any aspect of irony or decoration in your color choice? JL: Well, I have done patterns in the paintings before which were almost glowingly beautiful, and that doesn't disturb me really. However, it is how the elements are working against each other which I find most interesting. PORT: Does the notion of beauty play into your decisions at all? JL: I am quite in favor of beauty. I like it. There are a lot of artists and painters who are outright afraid of color. They use black and white consistently. But I fully engage color, not merely to the ends of making the picture beautiful, but there is a pleasure of color that I want to be in the paintings. This also has to do with the full experience of vision. PORT: Can you describe your process in the studio? I know you do a lot of drawings. JL: Yes I do. I do drawings and also miniature paintings on paper, which are studies for the larger paintings. Almost every painting has a study that precedes it. The painting can be fairly close in composition to the study. It's not mark for mark the same image, but there is a game plan before the painting starts. PORT: Does the change in scale ever destroy the image? JL: Yes, scale is very difficult. The miniature paintings are small models. Yet from small to large, the density of the mark changes entirely. When you're painting with very thick paint, you have to think in three dimensions as well as two. A certain mark can carry itself up to a certain size, but no larger. It's an unconventional way of making a painting in relationship to the concept of Action Painting which has dominated thinking about abstract painting over the last fifty to sixty years. However that method is only one way of working. These paintings aren't like that in the sense that they involve an aspect of design, and in this way they set their own convention, at least in the art of painting. PORT: Do you feel as if there are any other painters now who are working in this same convention? JL: I feel I'm a little bit of an oddball in that sense. Above all for me, it's not the act of painting that's important, it's the picture. PORT: Would you say that the viewer's experience is foremost in your mind when you are creating these images? JL: Well, I am very concerned that the picture is successful unto itself. But, I am extremely reception oriented. I really am interested in the viewer. I want the viewer to see him or herself in the act of viewing. I want them to be engaged, and I want them to work on the problem of the painting. These are very hermeneutic, very interpretive paintings. They make a proposition to the viewer and then the viewer has to work on what they mean to him or her. Somebody had once written that these paintings ask the question of the viewer that John Q. Public often would ask of an abstract painting, namely: 'What is that supposed to be?' These pictures wish to ask that back. PORT: When you talk about wanting an image to be successful, where do you think these ideas of a 'successful' image come from? Do you think it has to do with a sort of criteria based on this language you have created or do you believe it to stem from outside influences? JL: Well I guess I can only use myself as the primary viewer. I get opinions, but not that many. Basically, I am pretty much on my own in the studio aside from having an assistant there. So, it is very much how I see them. If I feel as if they're resonating in such a way that they're making the statement that I am trying to get them to make, then I feel that they're successful. Then of course, I feel that they are particularly successful if other viewers have that same experience. PORT: It's interesting because it becomes sort of ironic in the emphasis on the two dimensional surface, when in viewing these works, the experience can become almost three dimensional as your perception moves in and out of the ideas of a flat plane versus illusionistic space. JL: I am very interested in the things of the painting being things unto themselves, and that's where I felt they related most directly to Minimalism. The objects within the paintings are things you can think of as being in real world space, such as a figure on a background, which is also a thing unto itself and has an almost autonomous physical presence. It is almost as if you could lift that object off of the painting and set it down in front of us on its own two feet, and then the picture plane could exist elsewhere. That was my thinking about my work in relation to minimalism at the time I began doing these pictures. I was trying to beat minimalism it at its own game. PORT: All of your titles are very poetic. How do they reference this sort of argument of the ontology of impasto and flat line? JL: I think of the titles as being parallel to the spirit of the paintings. The paintings tend to be ambiguous, and the titles are often ambiguous. They deal with oxymoronic propositions, and the paintings have a bit of that. I mean, in this particular case it's almost a philosophical proposition: Reason and Free Will, it's a very Apollonian kind of statement. This one, Scenic Remembrance, is a landscapey painting. Reasonable Assembly refers to the nature of the picture, because you have all of these different components autonomously residing, and so I think of it as being a reasonable assembly of those forms.

PORT: Do you ever think of this ambiguity within the titles as being ironic or humorous or even making fun of itself in a way? Or do you consider this ambiguity to be more honest? JL: The titles kind of have a life of their own, no question about it. They're kind of my one line shot at being a poet. Actually there is a poet in England, Rupert Loydell, who had written a number of poems based on the titles of my paintings. PORT: I can see why. For me, these paintings seem almost linguistic, in a way, as if they are sort of humming in their own language. Do you think of writing, or script at all when you're making them? JL: My original intention was to make them very dialectical and to have them be conflicted images which would create a dialogue. I wasn't thinking so much of fully articulated language, but over the years, as that subject of language has been introduced and reintroduced, I am sure it has influenced my own thinking about the work a little bit, and I approach my painting a little bit more from a language point of view. But the big issue was not originally specifically language, but the idea that there was conflict and argument within the picture. PORT: Do you think that these arguments, the ones that were relevant as an answer to Minimalism, are still what keeps you painting now? JL: Well, I am not actively thinking of that any longer. After a certain point, you kind of have your own voice and are in a discourse with yourself. So, at this point, I guess I'm sort of talking to myself. (laughing) PORT: Which painters do you think have influenced your work and do you look at now? JL: Two painters who had a strong influence on me, primarily in my thinking rather than the actual appearance of the work, were Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg. The way they related to mark making is something I feel sympathetic to, the way they would take a gesture and isolate it, or use it as kind of an index or commentary within a painting, rather than as a mark unto itself. I was impressesd by their distant and cool approach. PORT: As if these solitary marks were characters instead of being the architecture towards the greater notion of the painting as a whole. JL: Yes, precisely. There were two other painters who influenced me very much in art school. Richard Artschwager with his thinking about the picture plane was interesting to me, because he is a painter just as much as he is a sculptor. Also Susan Rothenburg, who taught at CalArts for one semester while I was there interested me. She brought the issue of figure ground relationships up at Cal Arts, because that is something that she and certain other painters in New York were engaged with. Subsequently, a lot of these other painters who were doing that then went onto other things, and I kind of became the guy who carried on the project. In a way, I'm the guy who wrote the book on the subject. Those two artists as influences were a jumping off point to help me start these paintings. PORT: Do you feel as if the current art market as a sort of strange, but resounding critic will be affected by this current economic crisis at all? And if so, how? JL: I don't want to see a bad economy, but hopefully, less disposable income will pare things down to allow work that resonates to surface with more prominence. Sometimes it is good when the world has a time out. PORT: Do you see yourself moving into other visual languages in the future? JL: Well, of course I would move on if this form of painting no longer interested me. But I continue to find different ways to make these paintings, and this keeps me going.

Posted by Amy Bernstein on December 14, 2008 at 20:46 | Comments (1) Comments "It is almost as if you could lift that object off of the painting and set it down in front of us on its own two feet, and then the picture plane could exist elsewhere." When I saw this show, I felt as though I sh/could peel these shapes right off the canvas and they would stand up and walk away of their own accord. What Lasker does with figure/ground is fantastic. Wonderful interview Amy! Posted by: Megan Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)