|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

The Eye of Science: Brought to Light at SFMOMA by Bean Gilsdorf

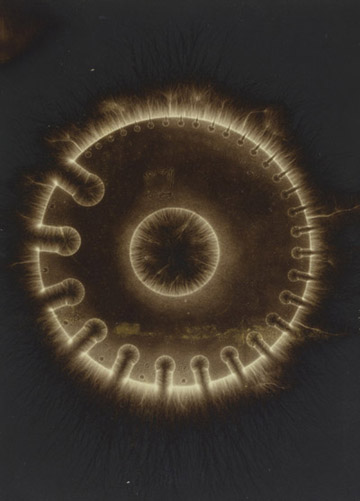

Hermann Schnauss, Electrograph of a brass wire gauge, 1900; Albumen print; 6 x 4 5/16 in. Imagine this: the world is new again. Photographs report the actuality of a novel universe, revealing truths about the environment heretofore unimagined. A formerly skeptical population is now awed, and hungers for images of phenomena previously hidden from sight, because seeing is both knowing and believing. One could ask why a modern art museum would exhibit a group of scientific photographs from the mid- to late 1800s, but Brought to Light answers with an unusual exhibition that highlights the power of curiosity and experimentation.  Arthur E. Durham, Photomicrograph of a flea, 1863 or 1864; Albumen print; 5 1/4 x 4 15/16 in. The invention of the photograph in 1839 coincided with an expansion of scientific interest and investigation, so it's not surprising that photography was enlisted for the cause; the photographs in Brought to Light document phenomena that are invisible to the naked eye. The exhibition contains obvious subjects: snowflakes, x-rays, microorganisms; as well as the more surprising: the magnetic fields of objects, the minute actions that comprise locomotion, the pulse of a 5 year old boy. Part of the charm of this show is the way it is organized, sorting the images into the scientific and pseudo-scientific categories of microscopes, telescopes, spirit photography, electricity and magnetism, x-rays, and motion studies. And although the exhibition contains over 200 photos, it does not feel cramped or redundant.

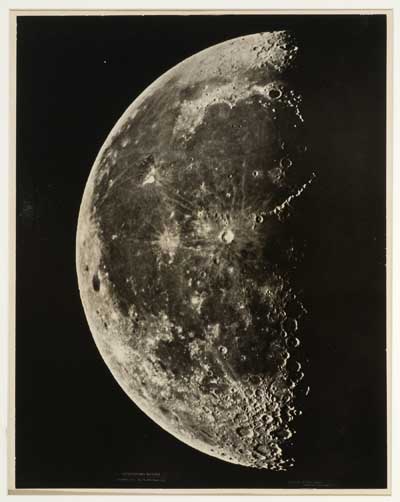

one of Wilson Alwyn Bentley's Snowflakes, before 1905; Printing-out paper prints; Twelve prints, each: between 2 3/4 x 2 7/8 in. and 3 1/8 x 2 13/16 in. The exhibition opens with microscopes, presenting images of snowflakes and tiny multi-celled organisms. For me, this was the weakest section, and I only appreciated its easy delights when I passed through a second time. But the juxtaposition of this material with telescopic images in the adjacent section makes the perfect foil. Here there is a whole wall devoted to the moon: 5 daguerreotypes, 15 large prints, and 22 small prints all displaying different phases and aspects. It may sound excessive to put 42 images of the same subject matter on one wall, but it was this abundance that made me acutely cognizant of how new this image was in the late 1800s: the distant power of a heavenly orb brought within reach of an ordinary public. Can you imagine what it was like to see the moon?  Edward L. Allen and Frank Rowell, The moon, made at the Observatório Nacional, Cordoba, Spain, 1876; Carbon print; 20 1/2 x 16 1/4 in. I have a keen interest in spirit photography, but to my disappointment I found the limited selection here to be insubstantial. Much stronger is the section on electricity and magnetism, where William Jennings' diminutive photographs of lightning (the largest was about 3" on the long side) are mounted to paper with Jennings' original notations inked in spidery script below each photo. The experience is richer for seeing these notes; photography is a medium that exists at a level of remove, and while these photographs are stunning, the notes underscore the humanity of the work. Likewise, the x-ray portion of the show is generally strong, but I was overwhelmingly drawn to Joseph Jougla's c. 1897 x-ray print of a foot in a shoe. This seemingly mundane subject is enlivened by the formal relationship of the foot and leg bones to the grommets and nails in the shoe, but it is the touching and poetic safety pin hidden in the hem of the trousers that makes the print so evocative. Sadly, the image of this piece and of Jennings' work (above) was not available to the press and, ironically, photography was not permitted in the galleries.

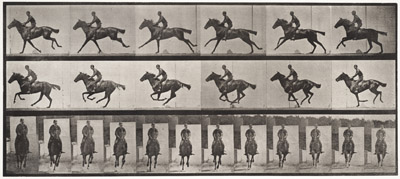

Eadweard Muybridge, Bouquet with rider, ca. 1887; Collotype Motion studies is another powerful section, one in which I was more aware of a direct influence on the arts. Eadweard Muybridge was well-represented by many of his animal motion studies, the best of which was "Cat Galloping", an 1887 collotype that is a prelude to the advent of motion pictures. But his most intriguing work here was "Spanking a Child" (also collotype, 1887), which unusually presented an illusion of motion created by six cameras arrayed in a semicircle. Atypically, the serial images in this piece record the changing angle of the camera, not the movement of the subject as in his other photos. Muybridge, of course, continues to have a profound influence on many artists, and the museum provides a kind of bonus room beyond the exhibition that showcases the more modern work of Abelardo Morell, Lew Thomas, H. E. Edgerton, and the Starn Brothers.  Etienne-Leopold Trouvelot, Direct electric spark obtained with a Ruhmkorff coil or Wimshurst machine, also known as "Trouvelot Figure"; 19th-century photograph; © Musee des arts et metiers, Conservatoire national des arts et metiers, Paris Admirers of alternative processes will find much to commend in the galleries: Trouvelot's photos of delicate phosphorescent creatures were created by putting a sheet of pewter under the photographic plate to record the different forms produced from positive and negative electrical poles. Oznam and Baldus joined a rubber membrane to a tube filled with mercury to produce photograms of the human pulse. Ducretet generated sparks both parallel and perpendicular to the photographic plate, exposing it in the process. The exhibition provides a kind of enchantment, where viewers can experience the wonder of the new through photographic images that are mysterious, grotesque, and poignant. Artists in particular should make an effort to attend, if only to imagine working in a virgin medium that, as part of the scientific zeitgeist, encouraged experimentation with no dogma to abide. But for all of us, living in a culture that often reduces even the best to a shrugging teenager---whatever---it is rare to have the chance to regain our sense of wonder at the world we inhabit. Brought to Light presents such an opportunity for marvel: a world in which there was much to be discovered. Bean Gilsdorf is a Portland multi-media artist and writer. She also contributes to Fiberarts Magazine. Posted by Guest on November 21, 2008 at 11:47 | Comments (2) Comments These are absolutely amazing. I especially love the last picture. Thank you for this. Posted by: sydneytherese Bean, Posted by: melia Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)