Vito Acconci at the Nevada Art Museum's Art + Environment Conference, 2008

I recently had the opportunity to attend the Art + Environment Conference at the Nevada Art Museum, October 2-4, 2008. Guided by the comments of the Lead Moderator William L. Fox, who is also the Lead Strategist for the Art + Environment Intiative, it was three days of excellent and thought-provoking presentations from artists, writers, curators and even a biologist. The NAM's staff were always very professional and courteous, which helped make the conference an outstanding event.

There are probably as many environments as there are people who might interact with them. Mr. Fox's expertise is in the exploration of how human cognition is able to transform land into landscape. The question of how we perceive ourselves in a variety of environments was a thread that created a common theme throughout the conference. Chris Drury and Lita Albuquerque both gave presentations of their work and their experiences about making art in Antarctica. Michael Light, Fritz Haeg, Katie Holten and Kianga Ford described how their work selectively reinforces or undermines visual cues and experiences in urban areas and suburban neighborhoods. Other artists such as Dan Goods were more interested in taking cues from natural pheonomena like wind speed and re-articulating it so that it could become art. Bill Gilbert described what it is like to take students out of the classroom and into the American Southwest, while Matt Coolidge thought that the way we divide up the views of the landscape often reveals more about ourselves than the landscape that we are looking at. Crimson Rose explained about what it is like to organize an event like Burning Man, and members of the Paiute Nation described what it was like to sustainably be a part of the land for the last 10,000 years.

The intention of the conference had been to bring to together as many ideas and perspectives on the environment as possible to see how ideas from different disciplines might cross-polinate. It was under these circumstances that I had the opportuntiy to speak to Mr. Acconci. The interview ranged from Marina Abramovic's recreations of Acconci's performance art and that of others from the 1970s and Acconci's perspective on his current architectural practice.

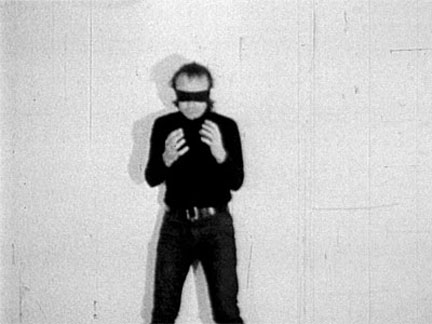

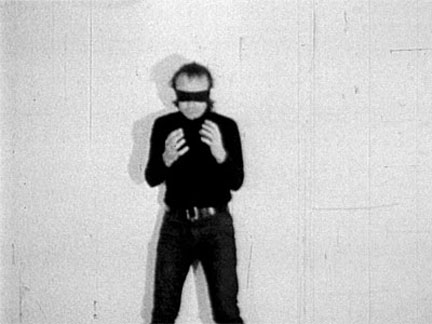

Vito Acconci

Three Adaption Studies, 1970

Video Still

Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix

In your early work, how did you know that using the experience of your body would be enough to make art? You understood early on that you did not necessarily have to create a painting or a sculpture but that your body and your experience could be the raw material for a new kind of art experience.

Because of the time. It was the late '60s and early '70s and the common language of the time was one of finding oneself, as if the self was something to contemplate. It was as if, at the time, that the self was a kind of precious jewel to concentrate on. Also it was the time of face-to-face encounters and encounter groups with an emphasis on person-to-person relationships. There were a lot of books at the time about non-verbal language, you know, how do people sit facing each other or whatever. It was a time when a lot of authority figures were being toppled, demonstrations against the Vietnam War, which was probably the most important thing about the time. It was also the time when the first Feminist writings were beginning to emerge. It was a time when, I do not think that I could say all of us, but some of us started to think that there was something wrong about art. There is something wrong about museums. We would ask questions like why do museums have no windows or few windows? Is art as fragile as all of that? Probably the answer is yes but, in other words, a lot of us wanted to see if art could be a kind of encounter. Can art be a kind of interaction? I am still not sure, but it was something that we wanted to explore.

But you were trying to push those experiences to see how far you could go.

It was not only me; there were a few of us. One of the interesting things about that time was that there were a lot of little art magazines around. There was one called Avalanche in New York, Intefunktion in German and Artitudes in France. It was a time, and this was true for me, I assume it was true for others, that when we first started to do this stuff we did not know what to think of it. I was in New York and I knew Dennis Oppenhiem was doing stuff that was kind of on the same track, but at the same time you thought, are we kind of crazy? But when you started to see that there was somebody in the Netherlands doing it, there was somebody in San Francisco, so you thought that maybe there was something in the air. There was something in the air, and maybe we are not making a mistake to try and catch on to that.

Vito Acconci

Follow Piece, 1969

Photograph

(c)Vito Acconci 2008

One of your early works that is one of my favorites is called the Following Piece, which was done in 1969. In that work, you are following someone around and you do not exert any control over the length or the locations of the work because you are simply following the other person until they go into a private building. You have to surrender your experience to whatever this person is doing and wherever they happen to going during that time. I always thought that it was really interesting because you are engaging in an art space that is completely individual and the people that you are sharing the streets with are just going about their daily lives. I always thought it was a very unusual way of mapping the trajectories of our experience within a city.

But when you say that I was in an art space, I was actually in a city space. But I was turning it into an art space but only for me, not for the person that I was following.

It implies that there is this overlapping of contradictory experiences. Even though you are existing in the same space, you are experiencing art, and the person next to you might be going to the grocery store.

Exactly. But what you said was exactly what I wanted. I knew at the time that I was using my own personal processes where I was doing some sort of activity. There was a question about how does something begin? How does something end? Then I thought, I do not want to pick the end point. I want to follow someone until I can't follow anymore, until that person enters a private place. I am not sure if you know but my background is writing and poetry. A way of talking about a lot of those of those first pieces might be that it was a way to get me off my writer's desk. (Laughs)

I was used to being in this place where when I was writing, the way I thought of writing was how do I move over this space of the page? How do I move from top to bottom, or the left margin to the right margin? So I thought of poetry as a way for me a as a writer to travel all over the space of the page. In turn, the reader can travel all over the space of the page. After a while though, I started to think that if I am so involved with movement, then why I am limiting this movement to an 8 1/ 2 x 11 piece of paper? There was a world out there. There is a ground out there. There is a street out there. So what was significant about those first pieces was that I was trying to get me out into the street.

Vito Acconci

Seedbed, 1971

Photograph

(c)Vito Acconci 2008

When we look at your early work now, it only exists as documentation. The work itself was experienced by you at that time, in that space and under those circumstances. People could recreate the project following your guidelines, but they could never experience it as you did. How do you feel about that?

You can never experience another person's experience. Just like when I was growing up, I would read articles about the Second World War. (Laughs)

I am only half kidding because if you are going to deal with an event or activity there really isn't a thing. You know the reason for not a thing was I think purposeful and was on the part of a lot us. Some of us were questioning what exactly was art? A lot of people of my generation were questioning things like the signature of an artist and how a De Kooning signature suddenly means millions. A lot of us were thinking is that what art is? Is art a way to separate those who can afford it from those that can't? But yes there is a flaw in everything that I did in that there is nothing there. It all depends on reportage and rumor.

How did you make the transition from being an artist, where everything is very temporal and it is about your personal response to your environment, to a situation where now something is built?

Not always. Well, a lot of it is not built but yes, it is meant to be built.

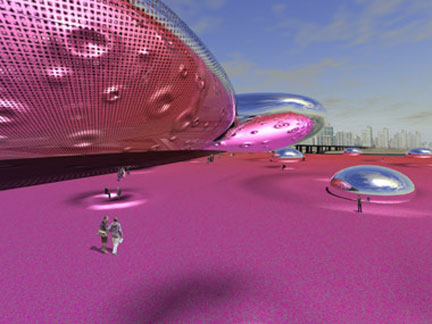

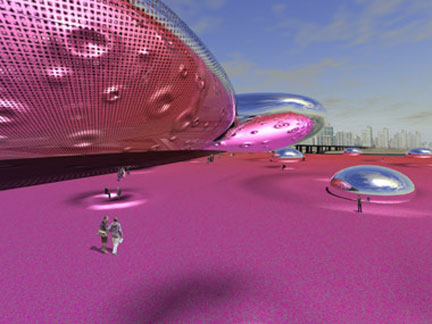

Acconci Studio

Seoul Performing Arts Center, 2005

Architectural rendering

(c)Acconci Studio 2008

As an architect you have to work with teams of people including other architects, engineers, contractors and clients to realize a project, whereas before it was just you. What is that like?

You brought up two very significant differences. The early work of mine was totally private. I mean maybe it had to do with the interaction of a possible viewer or whatever, but I was alone. Remember this was the time of music like Neil Young and Van Morrison, where there is a single voice in a long song. I think that a lot of stuff that I was doing and what a lot of people in art were doing is exactly the same thing. Just as they were doing in music; we were also a solo voice trying to find our self. In the mid '70s, live pieces started to fade away for me. They started to fade away for me because I began to have a lot of questions. I started to wonder if my work was so tied up to the previous decade. Is it so tied up with the '60s? Is it so tied up with the language of finding oneself?

But I was realizing that I and number of other people were starting to have very different notions of self. Maybe the self is not this private thing to be isolated. Why did people in the '60s go to meditation chambers? It was to isolate the self. But it was not the '60s anymore, it was 1972. A lot of us were starting to think that maybe the self exists only as part of a social system, cultural system or a political system. I started to feel that I did not know how to do live stuff anymore. Projects became installations in museum and gallery spaces. Now, installation is one of the vaguest terms in the world.

It was vague then and it is vague now. As usual, there were very few so-called movements that artists themselves named. They were always names by others, understandably because people need to find a way to talk about things that makes sense. But I think that those of us that were doing installations, probably each of us gave a specific meaning to the word installation. What installation meant to me was that I was given a museum or gallery space to do a piece in. I would almost never have a piece in mind until I had this particular space. Once I had a particular space then I would try to examine it. I would try to pick out the specific characteristics of the space so that the piece would come from the space. Ideally, it could not be done in another space. In some ways, it was just as temporal as a lot of the performances.

Vito Acconci

Where We Are Now (Who Are We Anyway?), 1976

Installation at the Sonnabend Gallery

(c)Vito Acconci 2008

That also parallels some of Robert Irwin's thinking about space and specificity.

Yes, very much. Did I know Irwin's work at that time? Sure I did. I think that there were a number of people that were trying to make a space rather than, perhaps space is not the right word. Perhaps it applies to how some people work. In Irwin's case maybe a more general term might be to make an atmosphere that people could be in. Another thing that was important to me about installations is that a gallery or a museum is a place where people are going to be. It is important to me that people are a part of whatever I am doing. The way I was thinking of pieces then, I was almost trying to turn the gallery space into a communal space. My pieces always use sound, and they probably use sound because I did not know how to get rid of myself so totally. I had to leave something behind. I was probably scared, I was so used to using my own person, I could at least leave a vestige of my person. An example would be a piece that I had done at Sonnabend Gallery in 1976, when galleries were still in SoHo, called Where We Are Now (Who Are We Anyway?).

Basically, it was a long table with stools on either side of the table. The table is propped up on the window sill of the gallery and then extends out the window. So what starts as a table becomes a diving board. There is a hanging speaker above the table, a constant clocking ticking and my voice coming in and saying things like: "Now that we are all here together, what do you think?" and "Now that we have gone as far as we can go, what do you think Barbara?", etc. I realized that what I liked about these pieces is that I was trying to treat a gallery or a museum as if it was a town square, as if it was a plaza, as if it was a community meeting place. At the same time I started to think I am kidding myself. A gallery or museum is never going to be a town square or a community meeting place, it is always going to be a private place. I thought that if my work really wanted or needed a public space, I better find a way to get out there. I started to redo architecture for myself. I thought there were already disciplines that deal with public spaces like architecture, urban planning, landscape architecture or even industrial design. I had to learn architecture. Gradually through the '80s, I started to think that I have to change my way of working. I can't work as a single person any more for two basic reasons. First, I wanted to do architecture, or something like architecture, but I really did not know how, so I needed to work with people who did know how. I needed to bring in people with an architecture background. At the same I thought that there was an even more important reason why I couldn't work alone anymore.

My background is in language so I have always been very affected by language. I became very obsessed with English language phrases like: "The person who lives by the sword, dies by the sword," that I translated into: Does that mean that work that begins private ends private? How do I get something to become public? I started to think that the way to begin is at least in a quasi- or semi-public way. It seems to me that public probably begins with the number three. One is an individual, two is couple, or a mirror image, and the third person starts an argument. So where you start an argument is where the public probably begins. So Acconci Studio started at the end of the '80s, and it has gotten maybe a little bit bigger. Now there are eight people in the studio besides me. In the beginning it seems like all we are asked to do were so-called public art projects, which I wanted to believe has a purpose, but I wonder. I wonder sometimes is that the fact that they exist as 1 percent art laws means that art is worth 1 percent of the architecture. I mean you can do things, but it is always a subsidiary. Gradually, maybe we have gotten into a position where people are asking us to do more architectural-like projects. The stuff I am going to show today is just my recent work. It was what the Acconci Studio has done in the, wait, what do you call the 2000s? I do not know. I also want to give the reason why we are doing what we are doing.

Marina Abramovic

Recreation of Seedbed, 2005

Guggenheim Museum, New York

(c)Marina Abramovic 2008

Marina Abramovic recreated your Seedbed for an exhibition at the Guggenheim a few years ago.

I have to admit that I didn't see it. I wasn't in town.

What did you think of her recreating these performance pieces? Was it interesting to you, and did she make it her own? She must have talked to you beforehand.

Yes, she asked permission of everybody. Actually the only person who did not give her permission was Chris Burden. Apparently Chris did not even talk to her and said: "If you take this any further, my lawyer's contacting you," or something like that. I do not know if I could say that I had mixed feelings. I do not know Marina too well now, but we did know each other through the '70s certainly. When she called I said: "Look, the way I felt about this piece is that I did something and anybody can take it, I do not even think that you need to ask me permission. At the same time, I am not exactly sure why you would do this over." To me, the performances came so much out of a particular time. Also at that time, there was something else that maybe caused my answer to her. I wasn't being disapproving, I was just saying: "Sure, do it."

I think that a lot of so-called performance artists have, and I know I have, been asked redo pieces, and I have always said: "No, it was a onetime thing." But that was how I felt. I think that she feels like she wanted to make performance art something that could be repeatable, like a piece of sheet music. That makes a lot of sense, and sure it is done differently by different people. Maybe that makes a lot of sense. At that time I know that I, and a lot of other people who were doing performance, wanted to very much separate our work from theatre because it is really very close. Artists perform and actors perform. For me, what separated performance from theatre was that it wasn't necessarily repeatable. It wasn't rehearsed. It was for me; again this is my version or kind of performance. For me performance depended on stage fright. I said I was going to do something. I really did not know if I could do it. The reason I think that so many of my pieces had voice was that I was almost talking directly to myself. I was trying to hypnotize myself into being there. Most of my performances had a time length, and it needed it because the first hour of a performance all I could think was: "This is the worst piece I have ever done. I gotta find some way to get out of here. But I don't know how to get out of here." And gradually, you talk yourself into something. For me, a lot of performance was stage fright and talking myself into getting rid of stage fright.

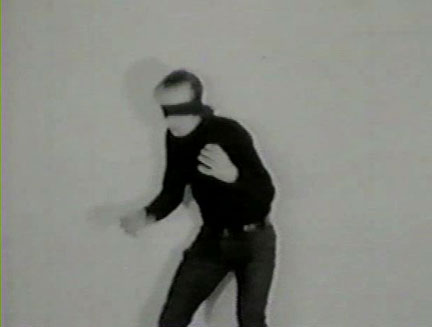

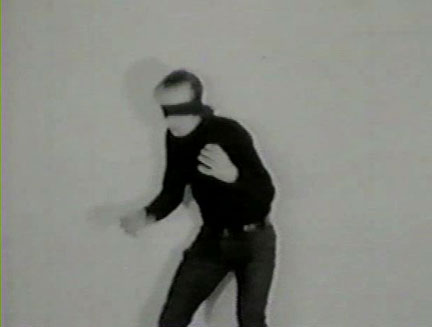

Vito Acconci

Three Adaption Studies, 1970

Video Still

Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix

It is good to know that you experienced it as well and that you were not some super-human that was immune to all of those insecurities.

I wanted it to be the opposite. I mean I think that a lot of us that were doing performance then, we wanted to be the opposite of the star figure or the maestro. We wanted to be like this is a person like any other person in the world. In the '70s, I was probably doing things that a lot of people were doing in the United States, in insane asylums! Mine were accredited by the art world. But it was a common ordinary thing. It did not need skill. It didn't need talent. It needed will.

A lot of PORT's readers are younger artists, and I was wondering if you had any advice for them?

Yeah, like I said, I am not even sure how much I am even involved with art anymore. But like I said whether it is art or architecture, I think that the only thing that is important to do is see what is around, take a convention, and see what happens if you turn it upside down. What happens if you turn it inside out? But this is a certain kind of art. Obviously, not everybody believes in art like that. Art is a process to something that was not there before. That sounds too grand, maybe it is like everything is already there but it could always be recombined. For me, I believe in art as a kind of way to change. Can I say that all change is good? Of course not, but all change makes at least some difference possible. Without change, I do not know how to be alive.

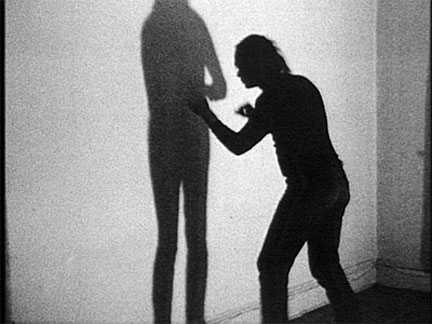

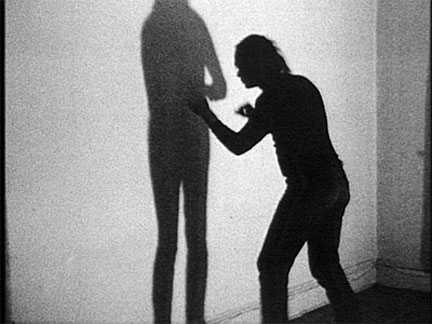

Vito Acconci

Three Relationship Studies, 1970

Video Still

Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)