|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

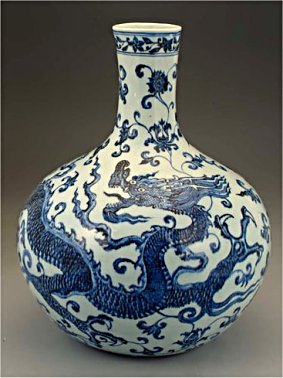

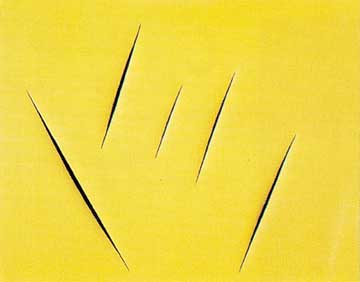

Interview with Garth Clark (exclusive)  Garth Clark Alex Rauch: You have been called a visionary. You are a gallery owner, curator, writer, historian and one of craft's preeminent intellectuals, associated with everyone from; Peter Voulkos, Anthony Caro, the Natzlers and George Ohr to Ken Price. And this Thursday you will be giving a lecture entitled How Envy Killed the Crafts Movement: An Autopsy in Two Parts. I guess a good place to start is how you would define the craft movement?  Peter Voulkos, Untitled, c. 1960; ceramic; 13.5 x 8 x 18 inches; Collection Museum of Contemporary Craft, Gift of the Margaret Murray Gordon Estate; 2004.10.03 Garth Clark: This you know has been a bit of a problem. The crafts themselves have really defined themselves as a kind of purgatory and it's a place where they wait until they've been accepted as fine artists. And this has been the debate which has been the single most destructive element in the field. The reason for it is very simple. This is the only community in the arts that gives the greatest kudos to those who escape. You know its almost like a penitentiary mentality. But the artists they revere are people who started in the crafts and eventually made it in the fine arts. A movement can't have much confidence or integrity with that kind of thinking. And its reached fairly extreme lengths now for example: the American Craft Museum changed its name to the Museum of Arts and Design [in a building designed by Portland's Brad Cloepfil]. Yet if you go to their current show for their new building that has just opened in New York probably 80-90% of the work on display in that museum is craft. So its sort of reminds me of the military's don't ask don't tell policy. It's fine to show craft there as long as it's not identified as such. It doesn't take a rocket scientist to work out that... "that" is an incredible kind of self-loathing, self-defeating kind of approach to a field. And to an extent this has always been this way. When this movement was founded hundred and fifty or so years ago in England by William Morris and others it was called the arts and crafts movement. The reason why it was called that is because they had to deal with a class issue. And that was that the people who were now member of the arts and crafts movement were mostly middle, upper middle and even upper class English. At the same time a craftsman in England at that time was a lowly worker. They were not celebrated or they didn't have any kind of prestige in their community. So if you think about it from the beginning what their title means by putting the word "arts" in is "better than craft". And that has stayed with the field year in year out. In 1959 Fortune Magazine did a very big article on ceramics the title even then was "The Art with the Inferiority Complex". So if you look at all of this and put it together you have a craft movement that is; running away from its name; that is trying to escape the crafts and get into the fine arts. You don't see that in painting. You don't see that in film. You don't see that in any other field. People try to rise to the top of their field. They don't try and escape their field. Which is what the craft movement has been doing. And then to make matters worse craft is not art... at least not fine art. The great craftsman is an artist. But that doesn't mean they are fine artist. Fine art is another discipline with a different set of values, different set of academies and a different set of theories. And my feeling has always been that the craft community has been trying to get into this party because of two things. One is ego. And the craftsman is supposed to be this selfless person who toils with materials and processes and is not hung up on the same kinds of things that the rest of the arts community are involved in. But in fact their egos are not just large, but in many cases kind of bloated.  Ken Price's Zig Zag from the Hammer Museum's Eden's Edge exhibition, 2007 With the ego they want to be seen as artists because artists are given this much higher profile in our society. And then on the other side this of this it is driven by something much more basic. The fine arts has the best rewards program in the culture world, people make tens of millions. And that is not unimportant. If we had the opposite situation were craftsmen made more money than artists (chuckling). The craft community would not be trying to force its way into the art world. So what it has done is left a completely demolished craft community. They once had an enormously powerful institution represent them called the American Crafts Counsel. It has in the last twenty years gone dormant. And has now clout no life whatsoever. Their flagship museum has taken their name off the portal. And this has happened with several craft institutions across the country. And all of this comes down to art envy. The Craftsmen are desperate to move crafts into the fine arts community. It's a very very peculiar thing. Alex: Why present a lecture on the crafts movement now when your gallery front has recently closed? Garth: The two are unrelated… Alex: Is it the market of the craft world? Garth: Oh, yes. Galleries are closing their front and center. The craft fairs which were once this enormous low end market for the crafts are beginning to shrink. And in between 1988 and 1995 the field lost most of its middle market which was craft gallery shops the middle market where people sold from five hundred to ten thousand dollars. And now the upper market where they sell from about two thousand and even up to a quarter of a million. That is beginning to fail as well. And you can't blame it on the economy because the failure started before the economy went down. And at the same time the crafts were failing the art world was booming along. And the most direct comparison which is the design world was probably having the greatest bull market of its hundred year life. So as people were spending more on their domestic objects craft was failing. So that tells you there is a great deal wrong with the craft community. To get back to the gallery and I had to correct the museum when they sent out a press release because they described me as a craft writer. I am not a craft writer. I am a writer on ceramics. And I'm not saying this because I would be embarrassed to be called a craft writer, but as a gallerist first in Los Angeles and then later in New York who worked with ceramics. We gave shows to people like Sir Anthony Caro. Who is considered the greatest living sculpture in Britain today. Lucio Fontana… a whole host of major fine artists. We've given exhibitions to artists who are definitely crafts artists. And we've also dealt with design and to an extent architecture. And that is because ceramics covers all of those fields. Our gallery was kind of a unique gallery in that it dealt with one material but it didn't keep itself limited to the crafts. We worked actively and successfully across the art, craft and design boarders.  Celestial globe vase, Ming dynasty, Yung-lo reign (1403-24), National Palace Museum, Taipei. Alex: Why does a Ming vase become a masterpiece? Is it because of the cultural standards that preceded it? Is this masterpiece considered an artifact? And what is the difference between art and artifact? Garth: Yes, there is a difference between art and artifact. But, it's a very subjective one. An art object is something which is deliberately made for that purpose. An artifact is usually applied to a beautiful object like a knife for instance. But even though it was made for a specific purpose is so beautiful it rises to the level of artwork. And objective because we are applying those boundaries to work from the past where we don't know how that work was made. In cultures in prehistory there is no way of knowing whether that beautiful knife constituted an artwork in that culture or whether it was just a knife. That's a very hazy thing. The thing about artists and craft is very simple. And that is certainly the best craft people are artists, period. They are the best artists within the craft. This isn't then a passport that they could just take into say… video art or the fine arts and have the same status there. And the reverse applies. You can take an artist from the fine arts and put them in the crafts and the work they make may not rise to the level of art by craft standards. It's not a complicated thing we are talking about, it is two distinct disciplines with their own cultures. And success in one is not automatically transferable into the other. Alex: How important would you say intent is manifested? Garth: It is fifty percent of the game. If you set out to make an artwork, clearly your intent is to do that. But it doesn't mean you are going to be successful. I'm mean, I sure you know a dozen painters and sculptures who are painters and sculptures but they are not artists. Their work is too mundane, too aggressive, too amatuere or whatever for you to really to take them and rise them to the level an artist within painting or sculpture. As I say the intent is only fifty percent of the deal. Because anybody can want to make art. But the desire to make art doesn't mean you are going to succeed at doing it. Otherwise art would be meaningless. There would be no artists in the world. Anybody could say this piece of paper is now art and it would become art. What happens is, the cultural community... first in your lifetime and then later after your departure weighs in on that and makes judgments as to whether it is art or not. There has to be on the other side of the street an acceptance for that... that what you had made was not just intent but does in fact go to the level of an artwork. I don't think any one individual can take the journey by themselves. Their work has to be met at a certain point and through criticism, opinion, taste, fashion, all kinds of things that come into play. We raise it to the level of an artwork. You see this in art school it's a very naive thought, "this is art because I want it to be art". It just really doesn't work that way. Otherwise we could start declaring all kinds of things we want to be art and by the intent would become that. It's not that simple. You have to earn that position in the arts. You can't just do it by your intent. Alex: Speaking of schools. How do you feel technology in schools is affecting to contemporize craft? Garth: I think its having a devastating affect on the crafts. One of the things you have to understand about the crafts and what makes it fundamentally weak in contemporary arts terms is that it's a revival movement. Modernism was not a revival movement, it was exactly the opposite. And so modern art and modern design really set off aggressively to shake off the past and create something new. And they succeeded. I mean modernism is probably the most significant art movement in the history of mankind. And at the same time craft was founded for several reasons. There was a socialist political background to it. William Morris who was the founders of the arts and craft movement was also one of the founders of the socialist party in England. The idea of a craftsman was linked to workers rights and works dignity and the rest of it. But primarily they saw the crafts disappearing and they wanted to save it from extinction. Well so it is revival movement by its very nature. That tends to drive "A" a nostalgia, which is not a good thing. It's like the sugar diabetes of art. It also pushes them to think backwards rather than forwards, going into the past to retrieve materials and to retrieve processes. And then lastly the movement was very, very anti-industrial. So basically anything that didn't comply almost with renaissance crafts standards was rejected. And as a result the craftsmen working today working in the old format of one person one material in their studio are having an enormously difficult time making ends meet. The craft studio business model is failing. And this is in part because they have not been able to move toward… I wouldn't even say technologies but processes. That will increase their production and give them a better chance of surviving in the market place. Because their still hooked in the, "if I going to make a pot, I'm going to throw it myself, I going to dig the clay" but of course that's an exaggeration. Some of them don't work that puritanically. But it is still a big problem. They can't come to terms with technology because technology in theory is the enemy of craft. Alex: So is it possible that the idea of "Avant-garde ceramicist" is interjecting intellectuality into a more aesthically driven media? Garth: That's been happening for quite a while. But again you can't achieve Avant-garde status because you say you want to do it any more than you say you want to be an artist because you want to be one. And what has been happening, not what all, there is a small fringe in ceramics that has developed ideas that are more in the line of mainstream fine art, which is where they belong. Avant-garde art practiced through art doesn't really make since. Craft is an evolutionary movement not a revolutionary one. And so if someone tries to make revolutionary ceramics and crafts they don't have an audience. And seeing as though they're making something that looks like fine art why not just make it in fine art and be done? What you have seen in ceramics, which has not been to its advantage is very simplistic ways of trying raise the intellectual and art value of the ceramics. Every other piece is ridden with footnotes from Genz and Michel Foucault is quoted every five minutes. But in most cases it comes across as a transparent exercise to give added value to what is being made. If you look closely the intellectual concepts they are dealing with are thin, they're tired, and you can find better examples of the same ideas in the fine arts. Because what they are doing is they are not working out of an authentic Avant-garde sprit. They are mimicking the fine arts. And when you do that it's a myth. There are examples of people who don't. I think one of the great examples is Grayson Perry. He's a British ceramicist. who won the top fine art prize in England the Turner Prize a couple of years ago. I don't know if you know his work? But here is this man who makes pots and against the Chapman brothers and all of these superstars of the fine arts wins the biggest fine art prize. He won it because his pots were very original and they were clearly from day one not dealing with craft they were dealing with fine art concepts. And again they were original. They brought something into the art world that had not existed before. What you see with the ceramicist is they keep attaching these ideas to the work again in the hope that they can get onto that bridge to the fine arts and onto the other side. But its not going to work. Because again they are imitating fine art not making it. And this is all now just a huge jumble in the crafts. People don't know what their doing anymore. They've become so confused as to whether they should be craftspeople or whether they should be trying to be artists or whether they should be in the fine arts. The whole movement is now enclosing. It's in totally disarray. Alex: Who would you say the most important ceramicist of the twentieth or twenty-first century?  'Concept Spatiale', 1959 by Lucio Fontana, 100 x 125 cm. Garth: That's interesting… the most important ceramicist of the 20th century is an Italian painter by the name of Lucio Fontana. Alex: Does he count as a ceramicist purely then because he is a painter too?  Fontana, Assunzione (1949/50) Garth: He's known as a painter. Everybody thinks of Fontana as a painter. He works with cuts and holes in canvases. So if you think of a red canvas with a knife slash running across it. Just a single slash, or two, or three... that is Fontana. And he is considered one of the greatest modern artists of the twentieth century. But the art world focuses on his painting, which really gave him international fame. But before that, Fontana worked in ceramics from the beginning of his career... for fourteen-seventeen years he worked solely in ceramics. And then he worked in ceramics throughout the rest of his career as well. And if you read his book there is knowledge of the ceramics in there. But the ceramics are not dealt with. He made thousands of pieces. He was an absolutely brilliant artist with the medium. He was very impatient and impulsive and sensual and the clay just formed a marriage with him that was just amazing. So, there you have somebody who's not from the crafts. Who probably at least in my warped judgment is the best ceramicist of the twentieth century. Alex: I think that's an interesting comment considering that one of your top ceramicists of the twentieth century is Marcel Duchamp. And he is obviously a purely a conceptual artist. Is there a purely ceramic artist that you would give paramount to? Garth: Duchamp doesn't really count, even though I am working on a book about the fountain. He had only one piece that involved ceramics and that is the fountain which is of course the urinal. You know it is interesting those things you jumped to immediately, because it seems like such a stark statement. But it really is a difficult one. Hans Coper is one that comes to the top of my list. He's a German-Jewish that fled to England and subsequently became one of England's best ceramists and one of the world's best ceramists. It's difficult to name one. It's easy with Fontana, because Fontana is utterly extraordinary and he sort of stands above everybody in the field. And he succeeded on so many levels. He worked with pots... he worked with figurative sculpture he had an entire career with abstract ceramic sculpture. He did buildings. It was an amazing career, which has not been documented. Again I have a bias, I am working on a book about it as we speak. I suppose into that list I would put Robert Arneson amongst the people who work specifically in ceramics. And Daisy Youngblood both of whom work figuratively. And on the playful side probably Hans Coper, Peter Voulkos and I'm sure when I put the phone down I remember a hundred different names. But those are certainly standouts within the century. Alex: Do you ever see any similarities between yourself and Clement Greenberg whose personal collection is at the Portland Art Museum? Garth: Ha ha ha. It is funny, there is a quote in the lecture from Clement Greenberg. I got him to... actually a partner of mine got him to... to speak at the first conference for the Ceramic Arts Foundation. This is an organization that promotes scholarship and criticism in the ceramic arts. And for our very first conference in 1979 we snagged him as the keynote speaker, which was a huge coup. And… I will answer your question in a second. But what he said at that conference I will never forget, which is exactly what I we've been talking about. He was very diligent. He spent eleven months examining the ceramics field and the rest of it before he gave the lecture. So when he arrived at that podium he was much more informed than you would have expected from somebody coming from the arts side. He had no real involvement in ceramics at all. And what he said to the audience was, "You strike me as a group that is much more interested in opinion than in achievement." And that nailed it! You know they were more interested in what they would be called at the end of the day, "Will I be called a fine artist? Will I be called a craftsman?" Than worrying about whether the quality of their work justified either of those labels. I don't see myself as Clement Greenberg for a number of reasons. I DON'T LIKE DOING THEORY. I do it from time to time. It's a very unpleasant process for me. It's like Pandora's box, you get the lid off and you can't put the lid back on. I much happier when I'm writing positively about artists who work I admire. I enjoy doing criticism as well. I don't mind being negative on that. But writing theory about art for me is just a pretty awful experience. The other thing where I think we differ is that Clement Greenberg thought he was right and wanted people to agree with that fact. It's not why I write. I write to stimulate discussion and challenge ideas and to topple sacred cows. But I don't think that what I write is necessarily perfectly true... or is going to be used by people one hundred years from now as the standard. It's a matter of acting in some ways as a goad, particularly in our field where intellectual debate is at a very low level. To get people to confront ideas. And very often the way to do it is to anger them. And I don't do that just for the fun of it. It's that somehow you have to get through the blandness of the craft community and get people to want to fight back. So when I write my idea of what success is... (it is) if it's caused a shift in ideas. Not if it's going to be the holy grail that people will read fifty years from now.  Bright Blue Bowl, 1968; Ceramic; 5.25 x 3 inches diameter; Museum of Contemporary Craft, Gift of Tom Hardy photo Dan Kivitka Alex: Are you familiar with Gertrud & Otto Natzler's exhibit at the Museum of Contemporary Craft? Garth: Oh, very much so. Alex: What are your thoughts on it? Garth: Perfect example of magnificent craftspeople. The Natzler's are not artists in the fine art sense. You can't take that bowl and place it next to a Brancusi and say that they are as much a fine artist as Brancusi. What you can say is that they have perhaps the same exacting standards of refinement that one finds in Brancusi's work. So these are really potters... they are craftspeople but they are very much at the top of their tree. Gertrude was probably one of the most skillful and fluid throwers of the century. I mean her throwing is gorgeous. Otto's glazes, which he designed or created for her work were often really remarkable as well. Although, behind the door Gertrude was often very unhappy with the choices he made on her pots but that aside it is brilliant work. Pure pottery doesn't get any more refined than the Natzler's, it is exceptional. Alex: Garth thank you for your time. It has truly been an insightful pleasure. Alex Rauch is a Portland artist who graduated from Linfield College in 2007 with BA in Fine Art and a minor in Art History. Posted by Alex Rauch on October 14, 2008 at 1:00 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |