|

||

|

Portland art blog + news + exhibition reviews + galleries + contemporary northwest art

|

||

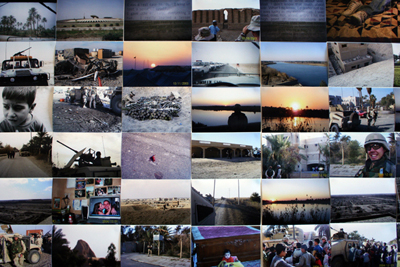

Exit Wounds  From lommassonpictures.com Jim Lommasson's Exit Wounds is not about art. It's not about politics or journalism either. It's about raw human experience: The suffering, the triumphs, the fear, the pride, the visceral truths that confront every individual touched by the violence of war. The project, originally conceived as a book of photographs and interviews, was inspired by Lommasson's father's recollections from "the fog of war." It took his father sixty years to tell many of his stories from WWII, and that's a very long time to keep a secret. With Exit Wounds, Lommasson hopes to provide a venue for local young veterans of Iraq to be heard now. The Couture award offered Lommasson the perfect opportunity to develop Exit Wounds as a non-commercial installation - the elements of the show do not make for a salable work of art - and in 2007 he began interviewing and collecting photographs. Some of Lommasson's portraits of his subjects first appeared in September 2008 in Portland Monthly.  From lommassonpictures.com The side walls of NAAU are each covered with a photo cloud. The photographs sprawl across the space, punctuated with Lommasson's large portraits of veterans. The clouds are surprisingly beautiful, the richness of Lommasson's large images blending with the vivid colors of the smaller photographs to create a pair of visually pleasing collages. The shape of the clouds develops organically down the walls, allowing the viewer to control the pacing of his or her experience. Although the skill of the artist's eye is evident in the layout of the photographs, their arrangement is unplanned, coming together naturally as Lommasson mounted the show. And yet, as we stood together in front of the photo clouds, he confessed to me that he couldn't move a single one. The pictures have wound together to construct an overarching narrative of the light that retelling casts into the shadows of memory, the clouds' pixellated edges left open to invite veterans to add more images to the story.

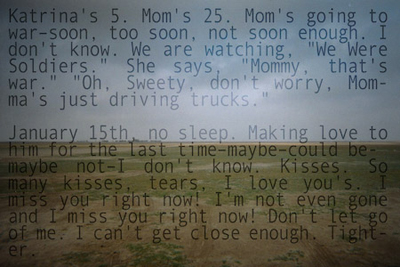

Upon closer inspection, the clouds break down into individual images of soldiers, landscapes, barracks, ruins, remains - everything and anything that caught the eye of a soldier in Iraq. It is impossible not to stare at the mangled body parts in several pictures, realizing that the lovely hue of red that caught your eye from a distance was someone's seared and bloody flesh. As your eye moves across the wall, images of funny graffiti and soldiers at play intermingle with destroyed bodies and buildings. There are as many beautiful sunrises as desolate urban landscapes, and the photographs carry a power that you won't find in photojournalism. Here you are confronted with the war as lived by the people fighting it, the moments that make up their daily lives, their vision, their view. Taking in these images is at once dehumanizing and very, very human.  Lommasson's skill as a photographer emerges in the beautiful portraits that he took as part of the interviewing process. In one image, we see only the shadow of Arturo Franco as he plays Call of Duty 4. Suffering from PTSD, Franco spends most of his time alone in his apartment, his primary source of human contact coming from other vets, physically far away, networked together to play violent video games.* This contrasts sharply with the bright image of Lucas Wilson, triumphantly holding up a pheasant on a hunting trip. Wilson's lifelong dream was to be a soldier, to take on the sacred and honorable role of protecting his country and its ideals. Even after losing a leg on his second day in Iraq, Wilson's belief in the mission is unshaken - "I got 30 seconds of my dream," he says, "I'd give my other leg to live it again." The portraits, scattered throughout the soldiers' photographs, expose a deep, abiding pain, but also a sense of pride, determination, and renewal. In an effort to better integrate his images into the clouds, Lommasson has broken down and mosaicked the portraits from their constituent parts, so that each individual photograph matches the 4"x6" format of the soldiers' pictures. He hopes to equate their pictures with his own. By reducing the overall presence of his hand, Lommasson attempts to relinquish the power of the artist - or documentarian - to express his subject, giving the soldiers the agency to tell their own stories.  From lommassonpictures.com Quotes excerpted from Lommasson's interviews are placed throughout the clouds. To avoid the "book on a wall" experience, Lommasson extracted statements from the catalog and placed them in faded black or white text over an open desert landscape. The text itself is no more necessary to explain the images than the notably absent "tombstone information," but by placing text over landscapes and weaving them together into the clouds, Lommasson has created a "spoken" equivalent to the photographs. The condensed quotes render the images' narrative explicit.

Although the photo clouds dominate the gallery, there are two other elements that make up the whole of the exhibition. On the back wall there is a tiny photograph of an American soldier, his face grim, an Iraqi child clutched to his desk. A stack of envelopes sits on a shelf below the photograph, labeled "An open letter to three Iraqi women". The letter invites a strong emotional reaction, and Lommasson wants to allow viewers to read it in the privacy of their homes. However, I recommend reading it in the gallery. The words are more powerful when experienced as part of the whole exhibition. The letter is written by the American mother of an Iraq vet to three Iraqi women whom she'll never meet, but whose lives are tied inextricably to her own through the tragedies of war. Her words function as a forceful reminder of the echoing effects of war on everyone, soldier or civilian. Around the corner, a video plays quietly on a small flat screen. This is War: Memories of Iraq was shot by members of the Oregon National Guard during their 2005-2005 deployment in Iraq. The film was produced by Lucky Forward Films, a group of war historians. Lommasson played no role in the making or production of the film, but it is included as part of his effort to allow the soldiers to speak with their own voices. The video is in every way as authentic and honest as the photographs and the letter, but it is not as emotionally gripping. Perhaps this is due to some exhaustion from making your way through the rest of the show, or the over familiarity of video violence. A television screen is a very effective tool for abstracting violence and emotion. Although the video is an important piece of the story through the soldiers' own eyes, it is not as successful as part of Lommasson's project.

Lommasson admits to entering this project with an anti-war bias. Given the current state of Iraq, it is difficult not to feel angry and frustrated with war, no matter your political leanings. But Exit Wounds is ultimately not about advancing a pro- or anti-war agenda. The vets he interviewed include anti-war activists and a deserter, but they also include people who believe in the fundamental importance of their mission. Exit Wounds is about giving a voice to veterans, and an opportunity for Lommasson's viewers to connect with their stories on a profound level. War is an undeniably easy way to tug on the proverbial heartstrings. But the elements of this exhibition possess a naked sincerity that asks you to let go of aloof, desensitized detachment. The show gains its strength from its power to make you react, not from shock, but from genuine emotional engagement. As Marine Eddie Black writes in the introduction to the catalog: "We find that we do not want to tell our stories to people who are incapable of hearing our stories with their heart." *Post-Script: Participation in Exit Wounds has helped Franco significantly with his PTSD symptoms. He gained some celebrity from his oft-used portraits, and has been able to be more active and socially engaged, including participating in the show's opening. This speaks volumes for the power of art therapy and the effectiveness of Lommasson's project. Exit Wounds runs October 17 - November 30. New American Art Union • 922 SE Ankeny • 503.231.8294 Posted by Megan Driscoll on October 31, 2008 at 10:22 | Comments (0) Comments Post a comment Thanks for signing in, . Now you can comment. (sign out)

(If you haven't left a comment here before, you may need to be approved by

the site owner before your comment will appear. Until then, it won't appear

on the entry. Thanks for waiting.)

|

| s p o n s o r s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Site Design: Jennifer Armbrust | • | Site Development: Philippe Blanc & Katherine Bovee | |