Barnett Newman

18 Cantos, 1963-64

A portfolio of 18 lithograph prints and one cover page

Copyright 2008 Barnett Newman Foundation

I should say that it was the margins made in printing a lithographic stone that magnetized the challenge for me from the very beginning. No matter what one does, no matter how completely one works the stone (and I have always worked the stone, as soon as it is printed) makes an imprint that is surrounded by inevitable white margins. I would create a totality only to find it change after it was printed-into another totality...There is always the intrusion of the paper frame. To crop the extruding paper or to cover it with a mat or to eliminate all of the margins by "bleeding" is an evasion of this fact. It is like cropping to make a painting. It is success by mutilation...The struggle to overcome this intrusion-to give the imprint its necessary scale so that it could have its fullest expression, so that it would not be crushed by the paper margin and still have a margin- that was the challenge for me. That is why each canto has its own personal margins...These eighteen cantos are then single, individual expressions, each with its unique difference.

-Barnett Newman, "Preface to 18 Cantos," 1964

The problem of the boundary, or how a work a work relates beyond the borders of work to engage the periphery, drove some of the most interesting work of the 60s. The boundary is how the viewer is able to separate the inside of a work from the outside or how a work separates or integrates itself with the outside world. It goes by many names: the frame, the pedestal, the border and the edge to list a few. It is how a viewer locates themselves as they are exploring a work. The boundary determines where the work stops and our world begins and vice versa. Barnett Newman's 18 Cantos are no exception and are especially interesting because they specifically highlight issues of boundary that might be latent and misunderstood in his paintings. For Newman, the printmaking process left an artifact that brought the idea of the boundary to the forefront of his thinking. His articulation of the problems of the boundary also coincided with work by other artists of the 60s including Donald Judd, Dan Flavin and later even Mark Rothko who had done some of the most advanced thinking on the subject. Perhaps no issue is now more critical than the boundary because it is ultimately about how artists integrate their work with the world around us. Newman's 18 Cantos are now on display at the Portland Art Museum.

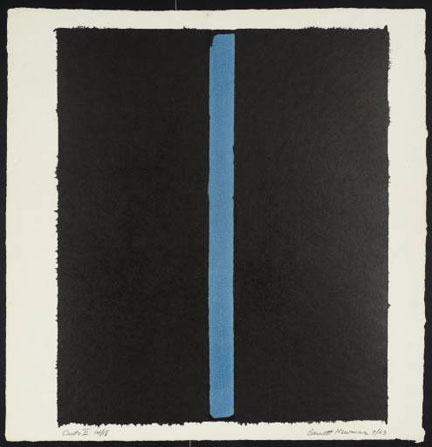

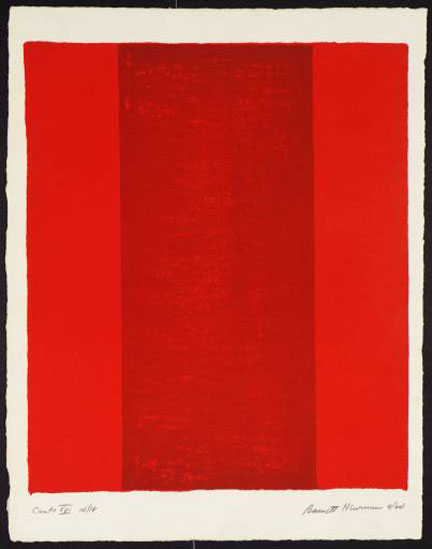

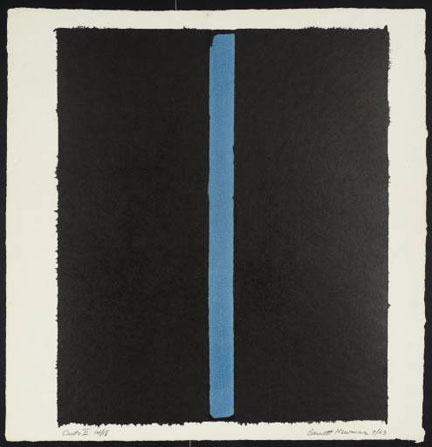

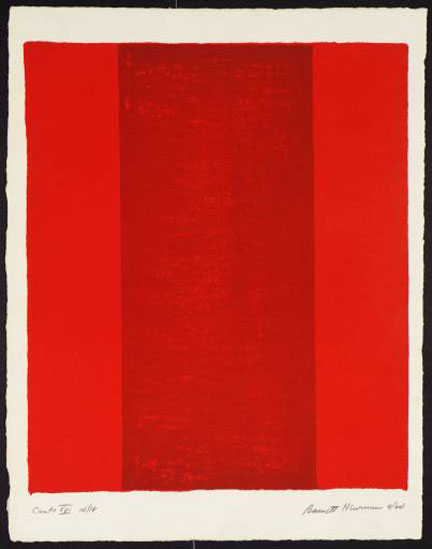

Barnett Newman

Canto II, 1963-64

A portfolio of 18 lithograph prints and one cover page

Copyright 2008 Barnett Newman Foundation

It must have been disturbing for Newman the first time that he saw one of the test prints. Although he had made prints before, this time he realized that something was different. When he was working on the lithograph stone, the process might have been similar to his process making a drawing or a painting. He was able to work to the very edge. He worked to the edge of the canvas because he wanted the painting to exist in our world and not as a window into another. In his words, he was able to create a totality. As the stone was applied to the paper in the press, the totality changed. Perhaps the image seemed smaller and more confined than what he had experienced on the lithograph stone and it was framed by a white border of unprinted paper along the edge. Everything that was clear and direct on the stone was now framed and separated from the outside world. The image on the lithograph related more to the field of the unpainted paper than the direct experience of everyday lives. The white border of unprinted paper worked against everything that he tried to achieve in his painting. It was a big problem.

It sounds pretty simple. If the paper that you are printing on is larger than the lithograph stone then you will have an unprinted border around the image. When we look at one of the Jasper Johns prints we hardly think about the border. It is simply a artifact of the printmaking process. In Johns' case where he is often making similar drawings in different mediums, the border even works in his favor because he is making sure that the print looks like a print and the image relates more to itself rather than the world beyond the borders of the print. In other works, Johns' prints are self contained. But Jasper Johns' process is different than Barnett Newman. Newman's paintings are about the paintings are about the direct experience of the painting as whole, as a totality, without an internal hierarchy. The paintings are experienced all at once, they are beyond an aesthetic experience. His paintings exist in our world and we relate to them with our physical presence rather than just our eyes. They help us understand what it means to exist as individuals. The white border of the unprinted represented everything that he had tried to get rid of in his painting.

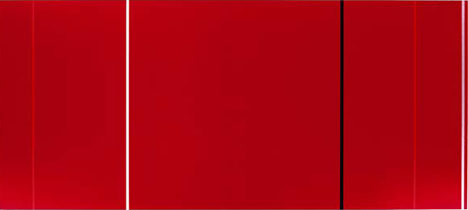

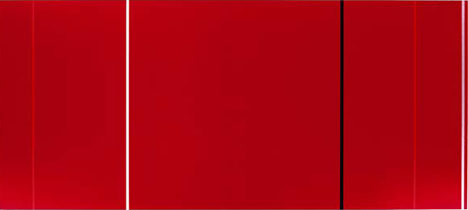

Barnett Newman

Vir Heroicus Sublimis, 1950-51

Oil on canvas

Museum of Modern Art, New York

Copyright 2008 Barnett Newman Foundation

Newman's paintings are about the direct engagement between the painting and the space of the viewer. He was able to move between these spaces because of the Zip. The Zip, in the most successful paintings, span the full height of the canvas allowing the viewer to use the Zip to locate their own body with the field of the painting. It is not bound by the edges of the canvas. Because the Zip exists in the full height of the canvas, it is not located in any field of color, it is a field in itself. Since the Zip is not bounded by the limits of the canvas it suggests that it might exist beyond the bounds painting or in other words, in the space of the viewer. The Zip is viewed as wider or narrower bands of color rather than a singular or series of stripes. A stripe by definition creates figure/ground relationships. It is a separation or division of the field. In Newman's paintings, everything is flat. Everything is on the surface. That is not saying that there isn't spatial ambiguity occasionally or that the complexity but that the complexity is explored through his handling of materials rather than as an a priori idea. We experience the painting wholly as a totality rather than as a composition made of different elements. It is the directness of Newman's painting that makes it so extraordinary.

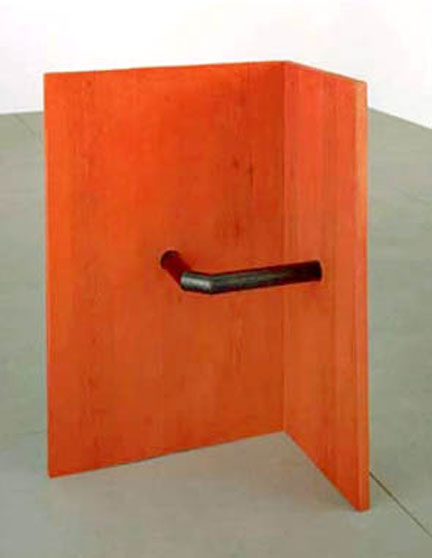

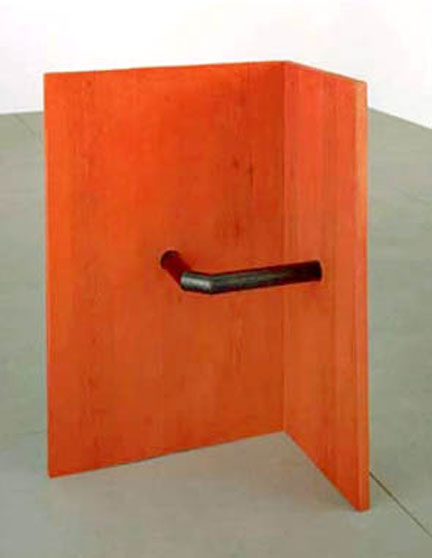

Donald Judd

Untitled, 1988, based on original from 1963

Stained wood and iron pipe

Copyright 2008 Donald Judd Foundation

Newman's articulation of the problems that are inherent in the boundary parallels the thinking by some of the best 60s artists about the translation from the space of the object into the space of the viewer. Work that addressed the issue of boundary in some way was representative of a shift in the works of a number of artists that were attempting to convincingly integrate their work into the environment in which they were placed. One example of another that was deeply concerned with the issues of boundary was Donald Judd. Judd began to place his work directly on the floor so that the entire space of the room became part of the field of the work. One of his earliest freestanding pieces deals directly with idea of boundary. Untitled(DSS-33) is made of two pieces of painted wood joined at one edge and are connected by an iron pipe that is welded together to form a "L" shaped bracket. In the original version they are painted cadmium red, in later versions the work would be stained.

Donald Judd

Untitled, 1978

Copper and red plexiglas

Copyright 2008 Donald Judd Foundation

The work is entirely about boundaries and how we separate and define one boundary from another. When we are looking at the work, how are we to decide the inside from the outside or the front from the back? The sculpture is about the tension between the space that is defined by the frame and the space that exists outside the frame. In a word the work is about a boundary. The relationship between the space that is contained on the inside or the outside of the piece is irrelevant unless the work is read in relation to the space of the room in which it is placed. The work does not exist except as a function of the space of the room.

It is easy to be able to distinguish between the interior or the exterior space of the work when you are physically close to the sculpture but as you move further away the definition of the spaces begin to blur and it is difficult to tell one from the other. Beyond the physical limits of the work the resolution of the boundaries is never clear cut. The work was designed to ask a question that it was never intended to solve. The indefinable space that exists between the panels is contrasted with the only space that is clearly defined as boundary in the piece, the iron pipe. It is the interior of the hollow metal pipe that connects the wood panels and resolves the tension and ambiguity of the wood panels. It is the only enclosed and clearly defined space. The work is about the tension that exists between the defined and indefinable. It is a work about limits and the tension that is created when those limits are breached. In Judd's mature work , the idea of the boundary evolves into the stacks and the large open rectangular volumes where the clearly defined exterior contrasts with an infinite interior.

Gerhard Richter

Six Gray Mirrors, 2003

Insalled at Dia Beacon

Dark mirrors on metal supports

Copyright 2008 Gerhard Richter

The idea of the boundary is also inherent in the work of another artist that followed Newman's work very closely, Dan Flavin. In Flavin's nominal Three (to William of Ockham),like most of his work with fluorescent lights, the volume of the room becomes the boundary of the work. By his skillful positioning of the fixtures, he could use the light to undermine or change our perception of the definition of the room. The relationship between the fixtures and the room is as important as the fixtures themselves. For example, by positioning the light in the corner of the room, he could use the light to flatten part of the corner. The work could not exist without the corner. The light of the fixture removes the shadow from the corner so that it seems to dissolve and the room becomes less three dimensional and more ambiguously two dimensional. Is Flavin's work the fixture or its effect on the room? It is not easy to separate the two. The room, like the white border of Newman's prints, it is an inherent part of the composition and the experience of the work.

Dan Flavin

the nominal three (to William of Ockham), 1963

Edition of three

Daylight fluorescent light

6 ft. fixtures; 72 inches high.

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Panza Collection

Copyright 2008 Dan Flavin Foundation

Here are two installations of Flavin's the nominal Three (to William of Ockham). William of Ockham (1288-1358) is famous for Occam's Razor: in a system in which all things are equal, the simplest solution is usually correct. Nominalism according to Wikipedia is:

"a metaphysical view in philosophy according to which general or abstract terms and predicates exist but that either universals or abstract objects, which are sometimes thought to correspond to these terms, do not exist."

The first installation is at the Guggenheim although I do not think it is on the ramp because the floors and the walls are perpendicular to one another. The photo demonstrates that the boundary of the room becomes the boundary of the work. The first and third fixtures are placed in two corners of the room and all of the fixtures are placed on the floor. The corners of the room at the level of the fixtures dissolve in the bright lights while the corner above the work remains clear and defined. In other words there is a tension in our perception of the between the upper and lower parts of the room. The installation changes the way that we perceive the space that we inhabit. The boundary of the work extends beyond the limit of the fixtures themselves.

Dan Flavin

the nominal three (to William of Ockham), 1963

Edition of three

Daylight fluorescent light

6 ft. fixtures; 72 inches high.

Copyright 2008 Dan Flavin Foundation

Sometimes it is easier to learn about what makes an installation successful by looking at an installation that is less successful. In the second installation the work is installed on a larger wall and the fluorescent lights relate more to one another than the wall itself. I do not think that the second installation was at the Guggenheim. In the second installation, the fixtures become much more like an object and the relationship to the volume of the room as a whole dissipates. In other words, in this installation, the fixtures relate more to one another than the space in which they are placed. The fixtures are also lifted off of the floor so that seem to float on the wall. Compared to the Guggenheim, I think that this is a less successful installation. In a strange way, by allowing the lights to only relate to one another and not the room as a whole, something significant is lost. One could extend this by saying that perhaps Flavin's art is not limited to the fixtures themselves but must exist in their relationship to their surroundings. Flavin's installations work best when they are grounded in the environment in which they are placed whether it is the corner where two walls or join or the seam in where the wall touches the floor. Without the connection to the space, they are just a series of fluorescent lights hanging on the wall. In other words, the boundary of the work is as important as the fixtures themselves.

Mark Rothko

Untitled, 1969

Oil on canvas

National Gallery of Art

Copyright 2008 Mark Rothko Foundation

Surprisingly when it came to dissolving any boundary that might be seen as a frame, Rothko was the exception, at least in some of his later work. A few years after Newman's prints, Rothko, in the development of his own process, began experimenting with a white frame around his paintings on canvas and paper. Perhaps it started when Rothko was painting on sheets of paper that were lined with tape to hold them against the wall. After the paintings on paper dried, the tape was removed leaving a white border around the image. Rather than cutting off the white border as he might have originally intended, he liked the way the white changed what was happening in the center. Rothko was insistent that the white line was part of the composition and not a frame. It was part of a new language in his work and was soon incorporated into some of his larger black and white paintings on canvas.

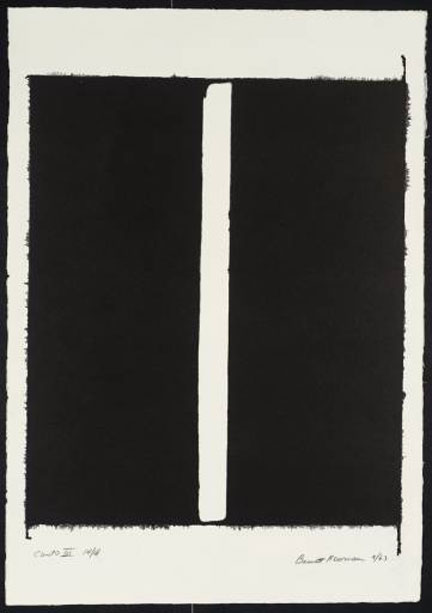

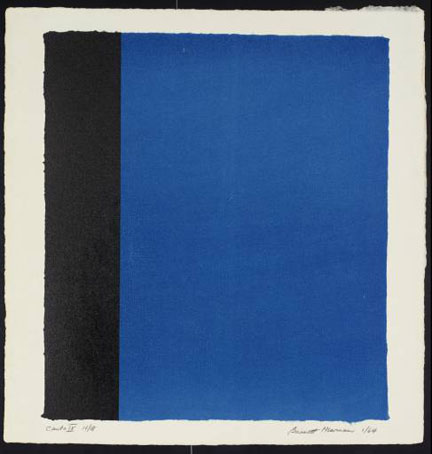

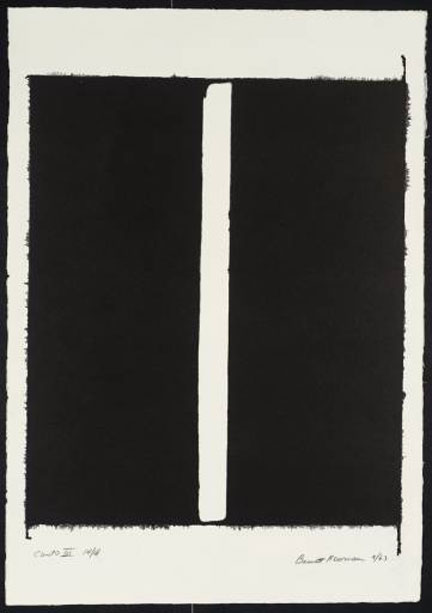

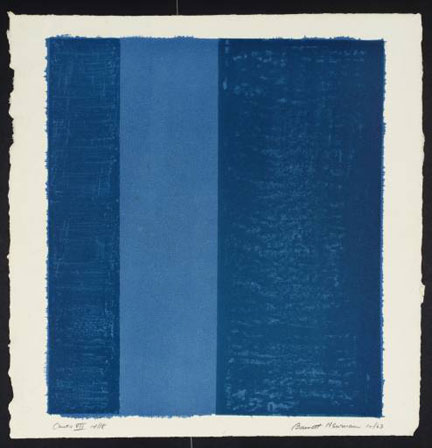

Barnett Newman

Canto III, 1963-64

A portfolio of 18 lithograph prints and one cover page

Copyright 2008 Barnett Newman Foundation

Newman's solution to the unprinted white paper border was simple and direct. The entire paper had to become an integral part of the composition. His work had to move beyond the borders of the lithograph stone. The totality could not be limited to the ink on the lithograph stone but had to accommodate the space, field and texture of the paper. It also follows that if the paper was to become an integral part of the experience of each print, then each print while being related to the others would have to be unique in the series. Each print had to solve the problem uniquely with its colors, its own proportions and its own internal relationships. It is interesting to note that Newman felt that some prints could have two equally good solutions, or perhaps they solve different problems, to the proportions of the print and so both variations would be included in the series. In most of the 18 Cantos prints, you can see the ink bleed around the edges of the lithograph. There is a looseness that blurs the boundary between the ink image and the white border. Even though it looks spontaneous, the bleeding is consistent across several prints so the bleed was on the stone rather than being the remnant of over enthusiastic application of ink. Everything about the prints, like his paintings, is very controlled and deliberate. The color and the geometry of the fields of ink are carefully matched to the proportions of the white border. After the test prints, the final size of the paper was prepared before the print was pulled. There would be no editing or trimming and the print had to exist "all at once." The result is that the prints are surprisingly dynamic and fit well with his paintings.

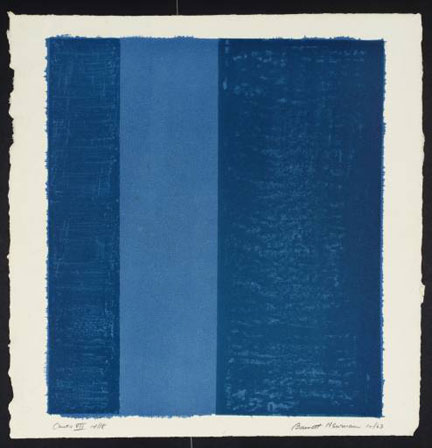

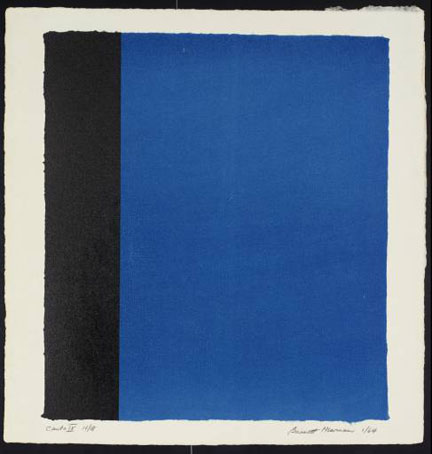

Barnett Newman

Canto X, 1963-64

A portfolio of 18 lithograph prints and one cover page

Copyright 2008 Barnett Newman Foundation

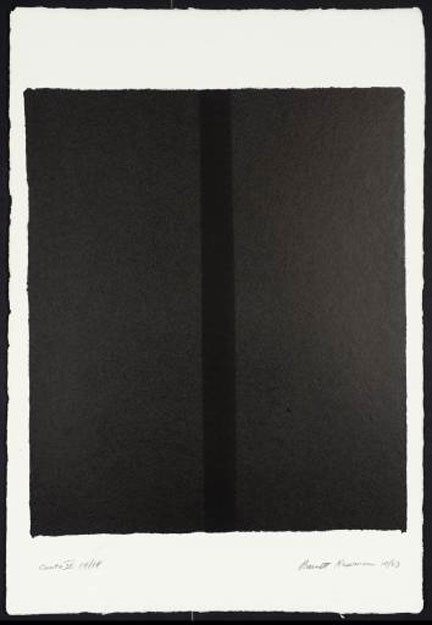

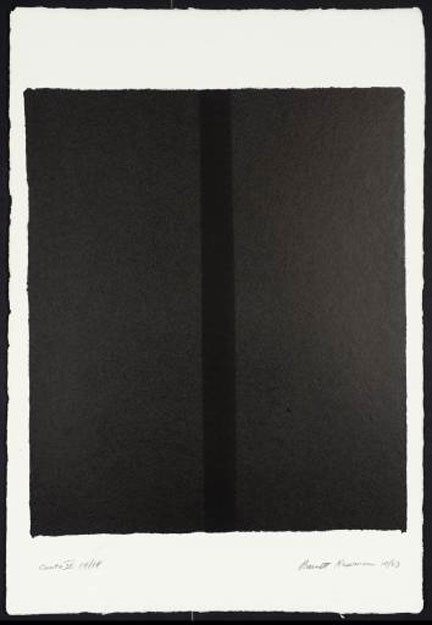

The proportions of the border changed the composition of the prints as well. In the black prints Canto V and VI, the composition of the prints is nearly identical. The only difference is the change in the white border. Canto V has a white border along the sides that is a little thicker than the zip itself. The white border frames and situates the black field on the unprinted white paper. In Canto VI, Newman must have felt that a white border would have worked against the contrast of the grayish ink to the black field. It is also revealing that because the paper is not trimmed afterward, there is a slight edge of white paper where there was a very slight mis-registration between the image and the paper.

Barnett Newman

Canto XVI, 1963-64

A portfolio of 18 lithograph prints and one cover page

Copyright 2008 Barnett Newman Foundation

Because the background of the print has to be printed first, the printing process is probably also a reversal of Newman's painting process. In Canto V and VI a thin translucent black field of the zip was printed before dark opaque black field was printed on top of it. This also happens in most of the color prints as well where the background color is laid down and the Zip field is placed on top. The Zip in these prints lets the background partially show through. This is an important idea that is worth discussing because it reinforces how Newman has always referred to the Zips as fields of colors of varying thickness rather than being simply vertical stripes. In the case of these early Cantos V and VI, the field of the Zip originally covered the entire field of the image. It was only in the second stage of the process that the Zip was formed by leaving a small thin area between the two black fields. The Zips exist on its own as its own and its size is based not on a design decision but how it other elements in the composition define it. In the prints the relationship between the zip and field is explicit because of the order in which the prints are made. In his paintings, the relationship between the zip and the field is more ambiguous especially because his Zips were occasionally created by painting over tape which was later removed to reveal the Zip.

Barnett Newman

Canto VII, 1963-64

A portfolio of 18 lithograph prints and one cover page

Copyright 2008 Barnett Newman Foundation

The 18 prints can be organized in a variety of different ways but the whole is always greater than the sum of its parts. The portfolio creates a very complex organic whole that exists beyond any predetermined system. There is a not a simple pattern or logic to prints. Each print is individual and unique. The prints are practically beyond categorization and one is inevitably forced to use statistics to try and discover overall patterns to the set, if any exist. Here are some of the simplest classifications:

Prints that share the same color and composition: Cantos V and VI. Cantos XV and XVI

Prints that look similar but are probably not: Cantos XVII and XVIII

Prints that might be based on the same plates but are in fact completely different: Canto III and IV

Prints that are nearly square: Canto VII, IX and XV

Prints with very little white border on the sides: Canto VI and XVII

Prints with asymmetrical compositions: Cants V, VI, VII and IX

Prints with very low contrast with the paper: Canto I

Prints with the low contrast within the composition: Canto IV, XIV, XV, XVI, XVII and XVIII

Prints made without color just black and white: Canto I, III, IV, V and VI

Prints in which the zips that are entirely or partially contained within the field: Canto I, II, III, V and VI

There are six prints with black, four with blue, three with yellow and five with red.

Each print is an individual solution to a unique problem.

Barnett Newman

Canto IX, 1963-64

A portfolio of 18 lithograph prints and one cover page

Copyright 2008 Barnett Newman Foundation

But the order of the set remains beyond us. There is always another classification. There is always more for us to discover. The system is indeterminate. The series is a system of complexity that transcends any simple idea or system. They are difficult and inscrutable, somehow always beyond the reach of our understanding and comprehension. Our only response is to surrender ourselves to the prints to see where it takes us. The experience takes place within ourselves. The experience, if it is to exist at all is transcendental. It is a system that one might have expressed itself as pure geometry but has instead become irresolvable and ambiguous or to use a phrase used earlier in relation to Judd's work, indefinable. The prints insist on being experienced individually because the system defies any order. Any idea of a system breaks down. The portfolio insists on being seen as a collective of individuals.

Barnett Newman

Canto IV, 1963-64

A portfolio of 18 lithograph prints and one cover page

Copyright 2008 Barnett Newman Foundation

Newman's 18 Cantos highlighted problems that were engaging some of the best artists of the 60s. By then, the best work was about a totality, or as Judd would say the object as whole. The art strived for a direct engagement with the physical space of the viewer and that relationship was destroyed by anything that suggested a border or a boundary. Newman wanted to get rid of anything that stood between the viewer and the experience whether it is was frame, a pedestal or anything else that prevented a raw direct experience with the work. This was explicit in his paintings but it was not until his work on the prints that he was able to articulate how important the boundary was for him and his work. The unprinted white border of the lithograph process created a white border that worked against his process in the same way that his painting of large fields of colors and Zip echoed the geometry of the stretcher bars worked towards moving into the space of the viewer. It is a problem that we are still struggling with today. These ideas are as relevant today as they were forty years ago. TV, movies and even the internet are to some degree are all experiences in which are passive spectators and separated from the action by the border or a frame. It is in contemporary art, perhaps more than any other medium, that the artist tried to remove the boundaries and to put all of us in the middle of the action.

Donald Judd

Untitled, 1989

Aluminium and blue plexiglas

Copyright 2008 Donald Judd Foundation

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)