Experience into Art: Robert Rauschenberg's The Lotus Series at Blue Sky Gallery

Robert Rauschenberg

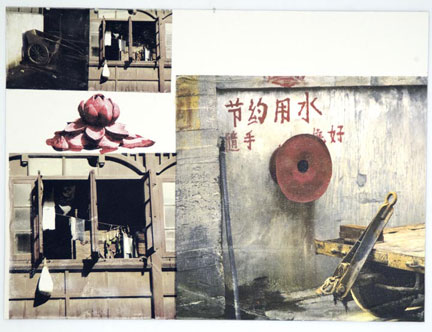

Lotus V, 2008

Pigmented Ink-jet and hand painted photo-gravure on Somerset velvet

45.75 in. x 60 in. x 1.75 in.

Print Edition by ULAE

Rauschenberg was a great photographer.

The first works he sold to the Museum of Modern Art in New York were photographs. The surprising thing is that even though he could capture whatever he wanted in front of a camera, it was never enough. Perhaps it was not real enough because the life and energy that would swirl around him seemed much richer and more complex than a single image from a camera. He needed something more, something different. He found that by collaging images along with the artifacts of a life he was able to create something richer, something as vibrant as the experiences he was trying to translate. Just as the image on the camera will be exposed onto a negative, at least it used to be before digital cameras, Rauschenberg wanted to insert himself into the process, to let all of the energy and experience to be exposed onto himself before being translated to the work. These new prints are extremely complex and bring together a lot of themes that Rauschenberg spent a lifetime developing. All of this comes together in a show of his last prints called The Lotus Series at the Blue Sky Gallery in Portland, Oregon.

Lotus Series installation at Blue Sky

When we are looking at The Lotus Series, like most of Rauschenberg's work, we never see a photograph in isolation. Even though Rauschenberg was an excellent photographer, at some level he must have felt that a single image would not be real enough. It would not be able to convey all of the life and energy that he saw spinning around him. The single image was too fixed, too stable, too much about one-point perspective. By contrast, he wanted to convey what it felt like to be alive. He was not trying to make art with the prints, but he was trying to show you the art that surrounds us everyday. Almost anything can be art; you just have to look at it in a certain way. In an uncanny way, he had the incredible ability to find Combines no matter where he went. Early on in his career he made them himself, later he just took photographs when he encountered them during his travels. Rauschenberg was opening himself to the world around him, trying to be open to the potential for art latent in his every experience.

Lotus Series installation at Blue Sky

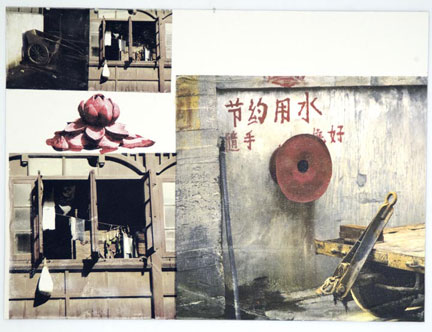

The new prints seem to be less about objects being photographed and transferred to a print, but more about the raw experience of a place. The original negatives from his trip to China (1983-85) were destroyed in a hurricane at his home on Captiva Island. Fortunately, small prints were discovered that would become the source images for these large-scale prints of The Lotus Series. These images were scanned by Bill Goldston of ULAE. Goldston was able to enlarge the images from the scan and correct the color. The next step was to print out the source images in different sizes so that Rauschenberg would be able to arrange the images for the final prints. The enlarged photos of his trip to China were made with an ink that allows the image to be transferred to another piece of paper by use of a solvent. This process eventually created an original, which was scanned and reproduced for the final prints. For me, this is a critical part of the Rauschenberg's process; the photographs were the starting point, not the end point.

Robert Rauschenberg

Lotus Bed I, 2008

Pigmented Ink-jet on Somerset velvet

60 in. x 45.75 in. x 1.75 in.

Print edition by ULAE

The transfer process is perfectly imperfect, and it's a technique that Rauschenberg had explored throughout his career. It is a way of introducing the artist's hand into the space of the photographic print. It is a way of undermining the focus and object-ness of a single image. It shifts the focus away from the information contained in the image to the human experience of the artist. The transfer process reveals itself as small bubbles or a bleeding edge of colors, as the source image slightly spills into the white ground of the paper. The result is a surprisingly tactile surface in which you can feel the artist's hand as he applies the images to the surface. The artist's hand controls and filters the images. It is the way that the photograph empowers Rauschenberg's process rather than taking something away. But the images were never enough, they had to be filtered, transferred and placed to so that they could lose their identity as singular elements and become part of the work as a whole.

It is the open-endedness of Rauschenberg's art that makes the prints so radical and subversive. His work is a direct engagement with the world around us. It is not about who we want to be or how we see ourselves but how we actually are. Not only was he looking for art in the everyday world, but he was also trying to leave a gap so that you would have an opening to be able to experience some of it to. The layout of the photos often leaves a white space somewhere on the print. For me, this space is our doorway to enter his world. It is a place where we can catch our breath before we move to the next image. It is Rauschenberg's way of leaving room for our own experience and allows us the space to participate in re-seeing the world around us.

I am always surprised at Rauschenberg's unflinching view of the world around him. If you were to take a quick look at the images in the prints, you would not find anything especially unique or even beautiful about them. There is hardly anything in the individual images alone would that would justify their use in these prints. In fact, the images look like a very a straightforward record of buildings and places during his trip to China, devoid of any art at all. And then the idea behind the prints hits you hard enough that it makes you have to stop to catch your breath. Everything has the potential to be art. Nothing can be excluded. You just have to see it.

For Rauschenberg, art and life were always linked, but both terms were too abstract to convey the experiences that he saw when he walked down the street. "Art" conveyed a sense of authority and permanence of work that was locked up in museums and galleries. You could say that before Rauschenberg, and maybe Duchamp, art was the opposite of what you saw when you were walking down the street. But the existing definition of art was not good enough for him, not by a long shot.

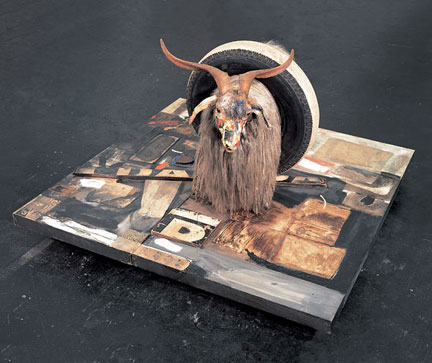

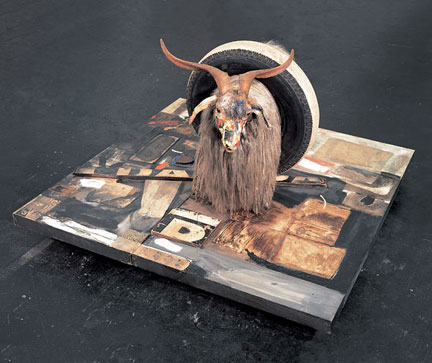

Robert Rauschenberg

Monogram, 1955-59

Stuffed Goat, rubber tire, paint, wood, signs

In fact, one could have made a list of things that were definitely not art. Bicycles - they were too utilitarian and functional and had nothing to do with art. Tires may have an interesting tread pattern, but they have nothing do with the beauty of classical Greek sculptures. Where was the beauty in a tire? Stuffed animals are definitely not art. Newspapers - if everybody had a newspaper how could it be art? Read them and throw them away. They have no intrinsic value except for the information they contain and a sort of nostalgia during especially newsworthy events. Cardboard boxes - fine for moving things around, but definitely not art. What would a cardboard box have to do with a Pollock or a De Kooning?

I think that Rauschenberg's genius was that he did not want to make art, or at least the way that art was defined in the late fifties. At the time you had all of the Abstract Expressionists hanging out at the Cedar Tavern, and they could tell you what art was about. In fact Rauschenberg, even asked De Kooning for a drawing. And then he erased it. Point taken. Rauschenberg did not want anything to do with what they called art. If the paintings of Abstract Expressionists were full of gestures and revealed some internal torment, he would paint canvases all black or all white with a roller. Their art was not his life. It wasn't the things that he saw walking down the street and in his own personal experience. If everyone came across bicycles, newspapers, mud, sliding doors, stuffed animals and cardboard boxes everyday, why are some materials appropriate for art and others not?

Like a great athlete, a great artist is able to redefine the very parameters of what we think is possible. Rauschenberg was no exception. The art of today is very different from the work of the Abstract Expressionists, in part because of Rauschenberg's ability to define what is possible in art, or maybe more accurately what is possible to make art. The less promising an idea or an object was for making art, the more interested Rauschenberg was in exploring its potential. His brilliance was his ability to make the resulting work compelling. His work reflects his own unquenchable thirst for life and experience. Everything had the potential to be art, you just have to know how to see it. Part of seeing an object is also accepting it as it is, without judgment. When we see the concrete lotuses in these prints, Rauschenberg loved them for exactly what they are. The lotuses are not particularly well crafted or beautiful and do not look like a real lotus, but that is exactly why Rauschenberg loved them. I suppose it is closer to loving something for all of its imperfections rather than its proximity to perfection. His work has an open-ended awareness and appreciation for the world around us.

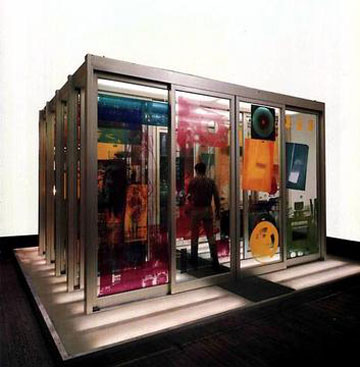

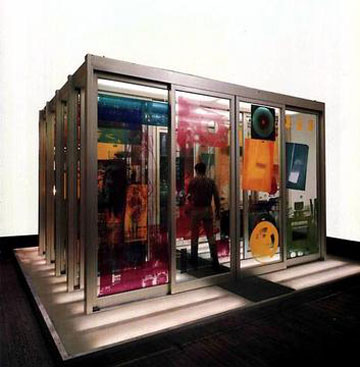

Robert Rauschenberg

Solstice, 1968

Screen Prints on automatic sliding glass doors over flourescent lights

Duchamp was probably the first one to realize that art had more to do with awareness than an actual physical object. Duchamp hedged his bests and made things to look like they were ready made even though they were custom fabricated. Rauschenberg took it one step further. He let the world around us speak for itself, and in a way that is completely astounding, made us think of the world as raw materials for other artists as well. John Cage would have been so happy. It is easy, when you are looking at the prints, to think that the dresses hanging in a circle at the top of the store are participating in dance that might have been dreamed up by Merce Cunnigham and his dancers. The dresses are dresses but more than dresses at the same time. The dresses begin to look like one of Rauschenberg's own combines. Or the numbers on the front of a store that are presented both forward and reversed might be a reference to a found Jasper Johns piece. The objects in the photos are presented exactly as you might see them walking down a street, yet when you look at the prints you are caught in a web of relationships and associations. Somehow the images are impossible to look at at face value, Rauschenberg's own history is interwined within them.

The concrete lotus is the recurring motif of the prints. Sometimes the flowers portrayed in the images are real, but often it a fake lotus that is applied as a photogravure - yet another layer of experience embedded in the prints. This hand-colored photogravure embosses the paper and provides a sense of the depth in the surface of the print. Just as the photographs are about different ways of looking at the world in which no single way is dominant, it is also important that the images are applied to the print using more than one technique. It is an art that is about awareness and opening our eyes to where we find ourselves. It is not an art that is just for museums or galleries. It is in our bodies, on our streets, in our homes, in the stores that we by our food and even in the way that we might we recreate the form of a lotus in concrete for a fountain. It is about the experience of continuous awareness without the need to isolate and categorize. Rauschenberg's lesson is that we can never be so confident in our judgment of the things that we experience to say that something is completely without art. We never know, and that is why we must always keep looking, learning and experiencing.

Robert Rauschenberg

Lotus II, 2008

Pigmented Ink-jet and hand painted photo-gravure on Somerset velvet

45.75 in. x 60 in. x 1.75 in.

Print edition by ULAE

But the images were never enough, they had to be filtered, transferred and placed to so that they could lose their identity as singular elements and become part of the work as a whole.

This reminds me of a comment Christopher Rauschenberg made in a Regina Hackett interview linked to earlier by Jeff:

Q: You're a photographer. Did your dad ever use anything you shot in his collages?

A: When he couldn't take them anymore I sent him a bunch of stuff. He didn't want to use any of it. He said, "These are already something. They aren't ingredients."

It makes me wonder both at the complex interplay in the father/son artist/artist relationship, and what Rauschenberg saw in his son's work that did capture a "complete" vision of life without the same level of intervention.

Thanks for your comment Megan. I remember hearing Rauschenberg talk about the goat in Monogram once. He started talking about how much he loved the goat, and the more he looked at it, the sadder he was that it had died. He thought that if he could put it in one of his works, it might be able to live a second life. That by itself is an interesting idea.

Rauschenberg worked on Monogam for four years. First off, Rauschenberg working on anything for four years is sort of a miracle, he was a very high energy and curious guy. It just tells you how much he was struggling.

For four years, no matter what he did it seemed like there was his work, the art, and then the goat. He tried putting it on the floor and then the wall but nothing helped. The goat just had an incredibly strong identity that prevented it from becoming art. It was always a goat.

Eventually, he learned that placing a tire around the goat and painting the goat, it was away of moving beyond the incredibly strong associations that we have of goats. Allowing for the potential for it to exist as another ingredient, to be able to become art.

The goat had to become more than and less than what it was in order to fit into the work. The goat had to become something else to be able to work as art. Like Christoper said, they had to lose their identities and become another ingredient to be able to fit into the work.

For me, this was a very subtle idea and a minor relevation. I am sorry if I did not do a good of explaining this idea but it made a big impression on me. Before, I thought that you could take anything to make it art, which you can, but you have to be careful how to use it.

![[TypeKey Profile Page]](http://www.portlandart.net/nav-commenters.gif)